1 Introduction 1

The rise of think tanks and the importance of scientific policy advice for political decision-making correspond with the diagnosed development towards knowledge societies [Nowotny, Scott and Gibbons, 2002 , p. 15; Stehr, 1994 , p. 10f]. On the one hand, the growing number of think tanks as well as their impact on public discourse and political decisions illustrate the increasing relevance of scientific policy advice today. Scientific-based expertise is especially high in areas such as environmental and energy policies, which are characterized by risks, complexities and uncertainties [Beck, 2003 , p. 276; Stehr, 1994 , p. VIII]. On the other hand, the growing number of think tanks signals a transformation in the relationship between scientific policy advice and politics. Traditionally, this relationship was characterized as “static” [Campbell and Pedersen, 2015 , p. 689] or “hierarchic” and “technocratic” [Münch, 2000 , p. 318] in France. The appearance of new think tanks led to the emergence of a field of scientific policy advice in France (and also in other countries) and to more competition among its producers [Campbell and Pedersen, 2015 , p. 691].

The change from the static relationship between scientific policy advice and politics to more competition among the producers of expertise involves “value dilemmas and competing orders of worth” [van Zanten, 2013 , p. 79] that the clients of expertise then have to deal with. The dilemma is intensified by the fact that think tanks’ expertise consists of several, non-standardized elements (scientific knowledge, political knowledge, mediation skills, etc.) [Grundmann and Stehr, 2012 , p. 16 and pp. 20–21; Weingart, 2006 , pp. 40–41]. In order to reduce these new uncertainties accompanying the exchange of expertise, think tanks refer to disposable and established principles in their communication so as to accentuate their competencies, to position themselves in the field of scientific policy advice and towards the other producers of expertise [cf. White, 1981 , p. 518]. 2

Against this background, this study aims at exploring the evolving field of scientific policy advice at the intersection of science and politics and seeks to identify the different cultural logics within the field used in the communication of its members to qualify their expertise and to legitimate themselves. This gives insights into the autonomy of the field as well as into the role of think tanks and illustrates how and to what degree think tanks serve as mediators between different logics.

To this end, the study refers to approaches from the sociology of organizations and from economic sociology. Its starting point is the analysis of the think tanks’ organizational identities to gain insights into the field of scientific policy advice. The organizational identities of the field’s members comprise the organization’s core qualities and reflect the environment’s expectations towards the organization as well as the relevant cultural logics in the field [Gioia et al., 2013 , pp. 125–126; Weber, 2005 , p. 228]. The cultural logics of the field represent a “tool kit” [Swidler, 1986 ] for the field’s members that they use “to solve different kinds of problems”, such as the task to obtain legitimacy or to state the qualities of their expertise [Swidler, 1986 , p. 273; cf. Beckert, 2010 , p. 610; Fligstein, 1996 , p. 660; Weber, 2005 , p. 228].

The field constitutes an autonomous sphere in which actors interact according to shared purposes and certain rules [Fligstein and McAdam, 2011 , p. 3]. For capturing the different cultural logics in the field of scientific policy advice, the study draws upon the modes of justification developed by Boltanski and Thévenot [ 2006 ]. The “orders of worth” [Boltanski and Thévenot, 2006 ] serve as an analytical framework for capturing the different cultural logics in society and within the field of scientific policy advice in France. To do so, the ways in which think tanks legitimate themselves and qualify their expertise are assigned to different modes of justification. By referring to these cultural logics, the think tanks also signal specific qualities of their expertise to their potential clients [Beckert, 2011 , p. 106; Diaz-Bone, 2015 , p. 181].

The explorative study analyzes the mission statements of 59 think tanks in France working in environmental and energy policies. The following section outlines the relevance of think tanks in France. Section 3 introduces the theoretical concepts that form the basis of the empirical analysis. Finally, section 4 presents the methodological approach and the empirical results that illustrate the relevant cultural logics in the field of scientific policy advice in environmental and energy policies in France.

2 Think tanks: definition and their growth in France

Historically, France’s centralized political system has mainly relied on government-funded think tanks and does not have a strong tradition of extra-governmental policy advice [Campbell and Pedersen, 2015 , p. 689; de Montbrial and Gomart, 2014 , p. 65; Murswieck, 2006 , p. 598]. Scientific policy advice has always been important in French politics, but it was embedded into the “static” and hierarchical relationship between government-funded organizations and politics [Münch, 2000 , p. 318; Campbell and Pedersen, 2015 , p. 689]. In this constellation, the main purpose of expertise was to provide means to steer social and technological change through the state, whereas the state was the only authority to set the goals for social and technological development. The task of expertise was not to provide a critical reflection about these goals or to set goals by itself [Münch, 1996 , p. 213; cf. Desmoulins, 2000 , p. 146; de Montbrial and Gomart, 2014 , p. 65]. 3

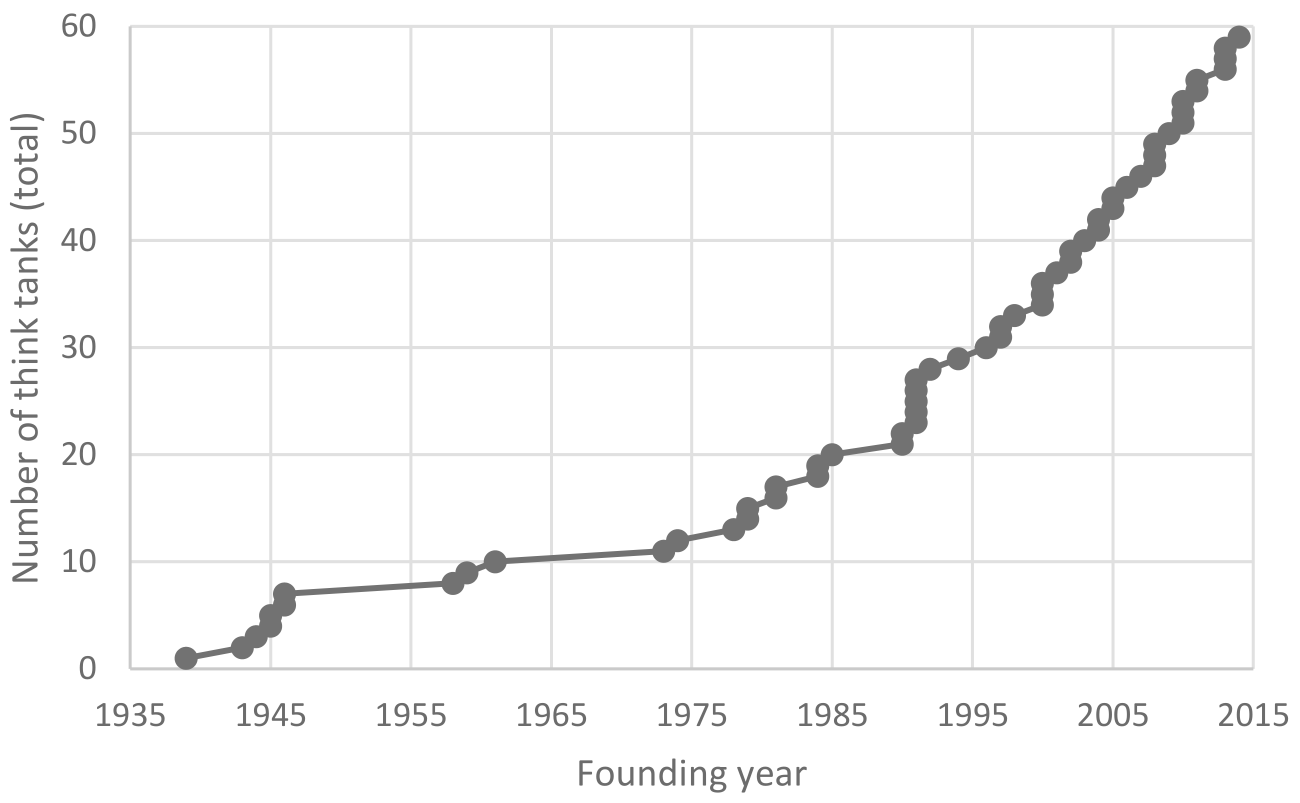

Since the 1990s, one can observe the emergence of more and more non-governmental think tanks (see Figure 1 ). Simultaneously, the demand for scientific policy advice has increased and the dominance of government-funded think tanks in the field has decreased slightly [Murswieck, 2006 , p. 590 and p. 595]. New actors have entered the scene (such as civil society organizations, parties, companies, industry federations) and have started to support the founding of think tanks [Boucher and Royo, 2009 , p. 104; Huyghe, 2013 , p. 13 and pp. 72–75]. Nowadays, the French field of scientific policy advice comprises government-funded and non-government-funded think tanks that differ in terms of their organizational features (size, age and financial sources) as well as the topics they are working on.

The growth of the field’s members has led to an opening of scientific policy advice towards the public sphere with the consequence that think tanks now increasingly participate in public deliberation. Nevertheless, think tanks are still struggling to find their place in the French political system and due to their relative newness in France, they seek to gain recognition and legitimacy [Boucher and Royo, 2009 , p. 119; Desmoulins, 2009 , p. 16; Medvetz, 2012b , p. 121; Stone, 2013 , p. 74]. These developments raise questions about their consequences for the relationship between politics and expertise in France, the role of think tanks and the autonomy of the field of scientific policy advice. For example, Campbell and Pedersen [ 2014 , p. 218] conclude that the French state has succeeded in integrating these new think tanks into the hierarchical and static relationship between politics and expertise [cf. Münch, 2000 , p. 318 and p. 344]. But the growth in the field may also have been a starting point for a fundamental change in the relationship between politics and expertise that newly defines the role of think tanks in France and lays the foundation for a more autonomous field of scientific policy advice.

In order to analyze the supposedly changing situation for think tanks in France, it is first necessary to discuss how think tanks are to be defined for the purpose of this study. As already outlined, it seems appropriate to speak of a “French exception” from the “American think tank model” [Desmoulins, 2000 , p. 140]. This leads to the question of what the fitting definition of think tanks is, because most definitions reflect the characteristics of think tanks in the U.S.A. [Medvetz, 2012a , p. 32; Stone, 2013 , p. 63]. 4 Some often used defining criteria — such as think tanks as ‘independent’, i.e. non-government-funded organizations — are hardly applicable to European countries, because they ignore the idiosyncratic developments of each country [Medvetz, 2012a , p. 31; Stone, 2013 , pp. 65–66; cf. Campbell and Pedersen, 2014 , p. 215]. Therefore this study applies an “operational” [Medvetz, 2012a , p. 15] definition that allows an identification of think tanks in different institutional settings and that captures their empirical diversity [Medvetz, 2012a , p. 36f]. Such a broad definition focuses on the central purpose of think tanks as organizations: the production of scientifically based expertise for advice in public policy questions [Grundmann and Stehr, 2012 , pp. 20–21; Weingart, 2006 , pp. 40–41]. 5 Based on this defining feature, this study has identified 59 think tanks in France that work at least partly in environmental or energy policies, though not exclusively (see appendix A ).

An additional characteristic of think tanks as organizations is that they are “internally divided by […] opposing logics” [Medvetz, 2012a , p. 23], because they participate in different spheres, such as politics, science, economics and civil society. This aspect influences their organizational structure, their identity, their strategy and their available resources [Medvetz, 2012a , p. 24; Medvetz, 2012b , p. 122]. In this understanding think tanks are “hybrid organizations” [Jasanoff, 1990 , p. 229; Mair, Mayer and Lutz, 2015 ; Medvetz, 2012a , p. 135], a term covering two aspects: firstly, “hybrid organizations (1) involve a variety of stakeholders, (2) pursue multiple and often conflicting goals and (3) engage in divergent or inconsistent activities” [Mair, Mayer and Lutz, 2015 , p. 714]. Secondly, think tanks’ tasks include “gathering, balancing, and assembling various institutionalized resources” [Medvetz, 2012a , p. 140]. Consequently, think tanks deal with different “cultural logics” [Diaz-Bone, 2013 , p. 49] to coordinate themselves and to cope with the environment’s demands [Thévenot, 2001 , p. 410].

As hybrid organizations, think tanks act as “mediators of knowledge” [Grundmann and Stehr, 2012 , p. 20] for politics as well as for citizens and between different spheres. Consequently, their expertise has to include several qualities: scientific knowledge, knowledge about the political possibilities and restrictions, their client’s demands and mediation skills [Collins and Evans, 2017 , p. 15; Grundmann and Stehr, 2012 , pp. 20–21; Weingart, 2006 , pp. 40–41].

As actors in the political and the public sphere, think tanks have numerous functions: they present (new) ideas to politics and the public [Stone, 1996 , p. 1], they contribute to political discussions through the publication of scientific findings or they scrutinize the information and assumptions under discussion [Campbell and Pedersen, 2015 , p. 680; cf. Neidhardt, 2010 , p. 30]. The think tanks do not always succeed in improving public deliberation and finding the best solution. This is mainly because advising is a contingent process dependent on numerous aspects, which need to be analyzed very closely. Furthermore, think tanks may also use their expertise to discredit scientific findings and to hinder public deliberation [Oreskes and Conway, 2010 ]. Strategies to discredit scientific expertise on environmental issues by counter-expertise can be observed in France, too [Schmid, 2018 , p. 43].

To capture think tanks as hybrid organizations along with the qualities of their expertise, this study uses the concepts of organizational identity (see section 3.1) and field analysis (see section 3.2).

3 Theoretical concepts

3.1 Analyzing organizational identities

Organizations follow goals “to cultivate an identity of its own” [Kühl, 2016 , p. 14]. These goals are rooted in society and refer to prevalent value orientations, e.g. that a research institute’s foremost goal is the pursuit of truth [Schimank, 2015 , p. 415]. 6 On the one side, external influences on an organization’s goals and purposes result from both regulations and “meaning systems” that guide their actions [Scott, 1995 , pp. 57–59]. Whereas regulations define the permissible actions of organizations directly, the meaning systems form the identity of organizations and thus have an indirect effect [Scott, 1995 , p. 61]. On the other side, organizations pick up and incorporate certain aspects from a meaning system to gain legitimation [Meyer and Rowan, 1977 , p. 340].

However, organizations and their identities are not externally determined. A focal characteristic of organizations is their ability to decide autonomously about their goals, their hierarchy and their members. Organizations need autonomy to meet their purposes and to improve their results, e.g. recruiting competent staff with regard to their specific requirements or creating innovative organizational structures [Kühl, 2016 , pp. 10–15]. Consequently, the task for organizations is to reach a balance between external demands and their “decision-making autonomy” [Kühl, 2016 , p. 14]. This task gets even more complicated for hybrid organizations such as think tanks, because different value orientations or logics clash within such organizations and compromises have to be found in order to meet the organization’s purpose [Lepsius, 2017 , pp. 38–39; Mair, Mayer and Lutz, 2015 , p. 714; Boltanski and Thévenot, 1999 , p. 359].

Identity is a central part of each organization because it embodies its goals and purposes and guides the actions of its members. It also reflects the environment’s demands and expectations to the organizations, e.g. from competitors, clients or a supervising authority [Gioia et al., 2013 , pp. 125–126]. Therefore, the organizational identity comprises the qualities and characteristics of the organization and their products that are “core, enduring, and distinctive” [Albert and Whetten, 1985 , p. 292; cf. Gioia et al., 2013 , p. 125]. The identity stabilizes the organizations and positions them as an actor within a field [Gioia et al., 2013 , p. 132].

Analyzing organizational identities makes it possible to capture the entirety of organizations and to draw conclusions concerning the field’s structures within which the organizations operate and which are relevant for them [Fligstein, 1996 , p. 657; Hoffman, 2001 , p. 136]. The analysis of mission statements is a common way of capturing organizational identities, because they contain the goals and purposes of the organization just as well as the distinctive features of their products [cf. Kosmützky and Krücken, 2015 , pp. 139–140; Philipps, 2013 ].

3.2 Field analysis

The study uses insights from field theory to describe the context in which organizations act and which affects their identity. Fields are “a meso-level social order where actors (who can be individual or collective) interact with knowledge of one another under a set of common understandings about the purposes of the field, the relationships in the field (including who has power and why), and the field’s rules” [Fligstein and McAdam, 2011 , p. 3]. Field analysis allows for questioning the interplay between networks, institutions and cultural logics in which actors are embedded as well as the relations between the organizational features of the field’s members, their resources and their position within the field [Beckert, 2010 , p. 605; Fligstein and McAdam, 2011 , p. 3]. This study aims in particular at exploring the different cultural logics within the field of scientific policy advice in environmental and energy policies used by its members to legitimate themselves.

Field analysis offers the opportunity to focus on the intersection between different spheres where think tanks as hybrid organizations are situated [Fligstein and McAdam, 2011 , p. 3]. Furthermore, the field perspective corresponds with the relational perspective on think tanks and their expertise and allows capturing the relations between the producers of expertise. The study of the organizational identities of think tanks is an explorative approach to scrutinizing the field of scientific policy advice in France [Hoffman, 2001 , p. 136]. To capture the field comprehensively, it would also be necessary to analyze its networks and its context conditions.

3.3 Sociology of justification as an analytical framework

The study applies the modes of justification approach [Boltanski and Thévenot, 1999 ; Boltanski and Thévenot, 2006 ] for capturing the different cultural logics in the field of scientific policy advice for several reasons: (i) The approach connects the macro-level with the field and the organizational level. (ii) It allows us to identify conflicts and consensus between different logics. (iii) For further research, it serves as an analytical framework that enables both cross-country comparisons and comparisons over time.

Action as well as a field’s order or the way of coordinating in organizations all rest upon the conventions that legitimate and guide them [Blok, 2013 , p. 495; Thévenot, 2001 , p. 405]. With this principle in mind, Boltanski and Thévenot identify sets of conventions in societies, which are each “built around an order of worth” [Boltanski and Thévenot, 2006 , p. 74]: (I) the “civic world” constitutes an order of worth according to which “general interests” are the highest “common good” [Boltanski and Thévenot, 1999 , p. 371]; (II) worth in the “industrial world” “is based on efficiency” and usefulness [Boltanski and Thévenot, 1999 , p. 372]; (III) the “market world” values free competition and individual success most highly [Boltanski and Thévenot, 1999 , p. 372]; (IV) “the world of inspiration” stresses independence and innovativeness [Diaz-Bone, 2015 , p. 152]; (V) the “connexionist world” understands action as a project for which coordination skills are indispensable [Diaz-Bone, 2015 , p. 153]; (VI) the green order of worth is related to the preservation of nature and environmentalism [Blok, 2013 , p. 496]. 7

The orders of worth as different modes of evaluation become apparent in “critical moments”, when “something does not work” or the legitimation of an order is questioned due to a competing order [Boltanski and Thévenot, 1999 , pp. 359–360]. In that case, the orders of worth serve as an analytical tool for capturing the different articulated claims for legitimation. To evaluate the worth of a matter or a being as well as to find an agreement in such situations, a “principle of equivalence” is necessary as a framework to compare the claims based on different orders of worth [Boltanski and Thévenot, 1999 , pp. 361–363]. One way to end such critical moments is to find a compromise that encompasses different “modes of evaluation”. Such compromises are also potential starting points for a new order of worth [Boltanski and Thévenot, 2006 , p. 283].

The orders of worth also serve as a “typology of cultural logics” for analyzing the coordination in fields and in organizations [Diaz-Bone, 2013 , p. 49; Diaz-Bone, 2015 , p. 181]. Applied to fields and organizations, the logics represent “legitimate principles” for evaluating the field’s structure and its members [Diaz-Bone, 2013 , p. 49; Thévenot, 2001 , p. 409]. Both organizations and fields encompass different logics and the organizations have “to cope with critical tensions between different orders of worth” [Thévenot, 2001 , p. 410]. Consequently, organizations position themselves by referring to established logics and in relation to the other field members [Diaz-Bone, 2013 , p. 49; Thévenot, 2001 , p. 418]. The empirical analysis applies the orders of worth as an analytical framework capturing different logics that the think tanks apply to gain legitimacy and qualify their expertise. By doing so, the analysis of the think tanks’ organizational identities offers the opportunity to gain insights into the criteria that characterize their expertise and captures the prevailing cultural logics in the field of scientific policy advice in France.

4 Analysis

4.1 Methodological approach and empirical implementation

The aim of the analysis is to identify the cultural logics that think tanks use in their mission statements to legitimate themselves and to characterize their expertise. The study applies a content analysis to examine the 59 mission statements dating from the year 2015. 8 Firstly, the content analysis aims at identifying the justification of think tanks as well as the qualities they use to describe their work and their expertise. The identified codes summarize the statements and structure them according to different meanings. The second step is assigning the codes to Boltanski and Thévenot’s orders of worth [ 2006 ] as a framework. This follows a mainly deductive logic because the orders of worth structure the coding scheme. Nevertheless, the coding scheme is open to include new codes which seem to be important [Mayring, 2014 , p. 104].

The units of analysis are sentences or bullet points in the mission statements. In every single unit of analysis, each code is assigned only once so as to calculate the “emphasis” of each code in relation to the sum of all codes within a mission statement [Weber, 2005 , p. 241]. 9 Hence, the analysis discovers the “relative prevalence of different elements in an actor’s toolkit-in-use” [Weber, 2005 , p. 242]. This approach respects the fact that organizations follow several logics, which are not necessarily coherent [Weber, 2005 , p. 228]. By assigning the codes to the orders of worth and by summarizing them, the analysis reveals the “relative emphasis” of the different orders of worth in the field [Weber, 2005 , p. 241].

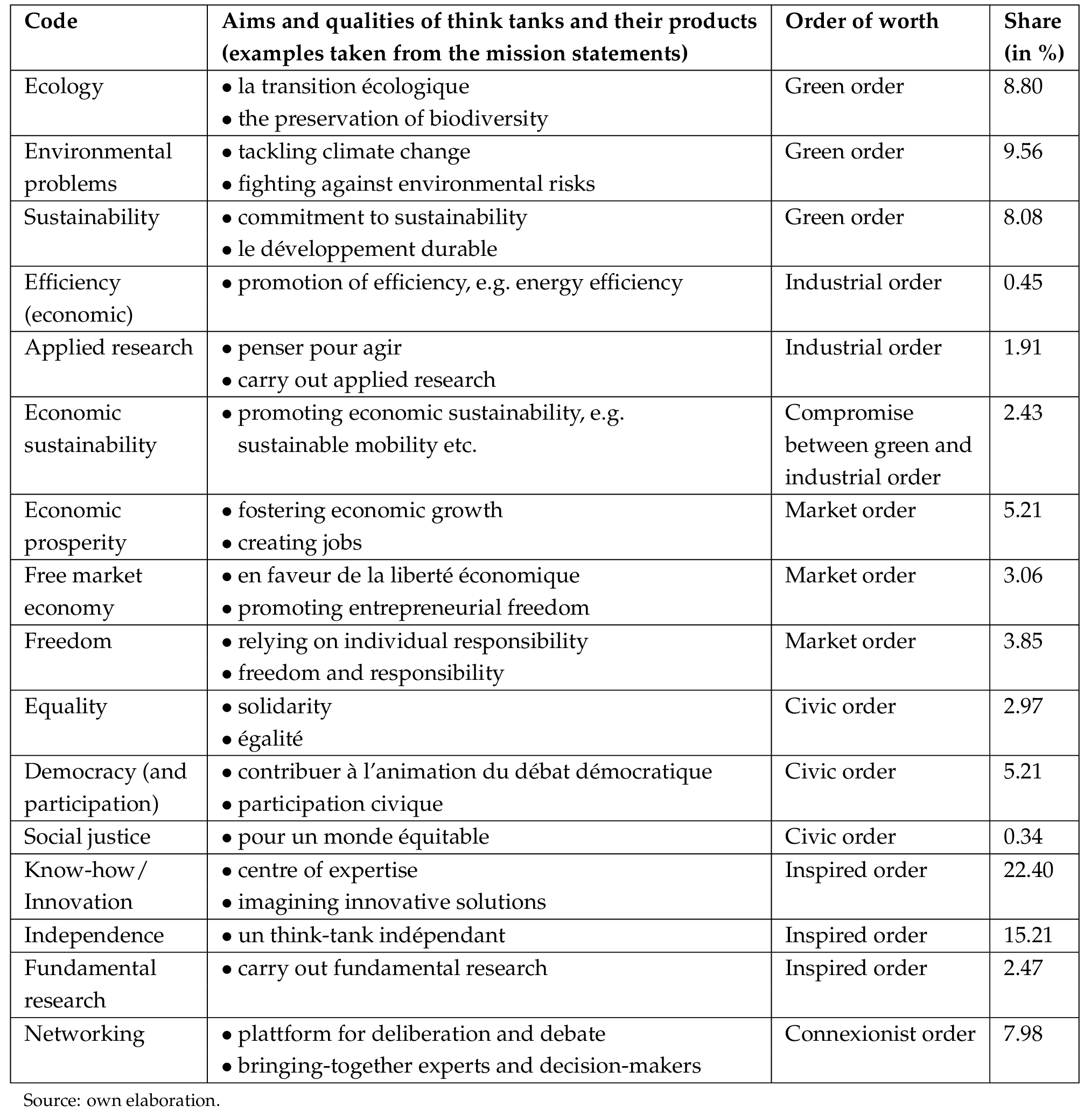

The content analysis identified 16 codes in the mission statements of the 59 think tanks. Table 1 illustrates the codes by showing some examples from the mission statements and reports the relative share of each code in all analyzed mission statements. Furthermore, Table 1 shows how the codes are assigned to the orders of worth, e.g. democracy and equality are essential qualities of the civic order, just as ecology and sustainability belong to the green order [Diaz-Bone, 2015 , pp. 152–153] (see also appendix B ). 10

The code “economic sustainability” cannot be assigned to one single order of worth because it represents a compromise between the industrial and the green order, which brings together different logics [Boltanski and Thévenot, 2014 , p. 367]. It is the only noticeable compromise in the mission statements. As far as its meaning is concerned, it is close to ubiquitous compromises like “green economy” which have gained prominence over the past few years [Blok, 2013 , p. 500; Caradonna, 2016 , p. 208].

4.2 Results

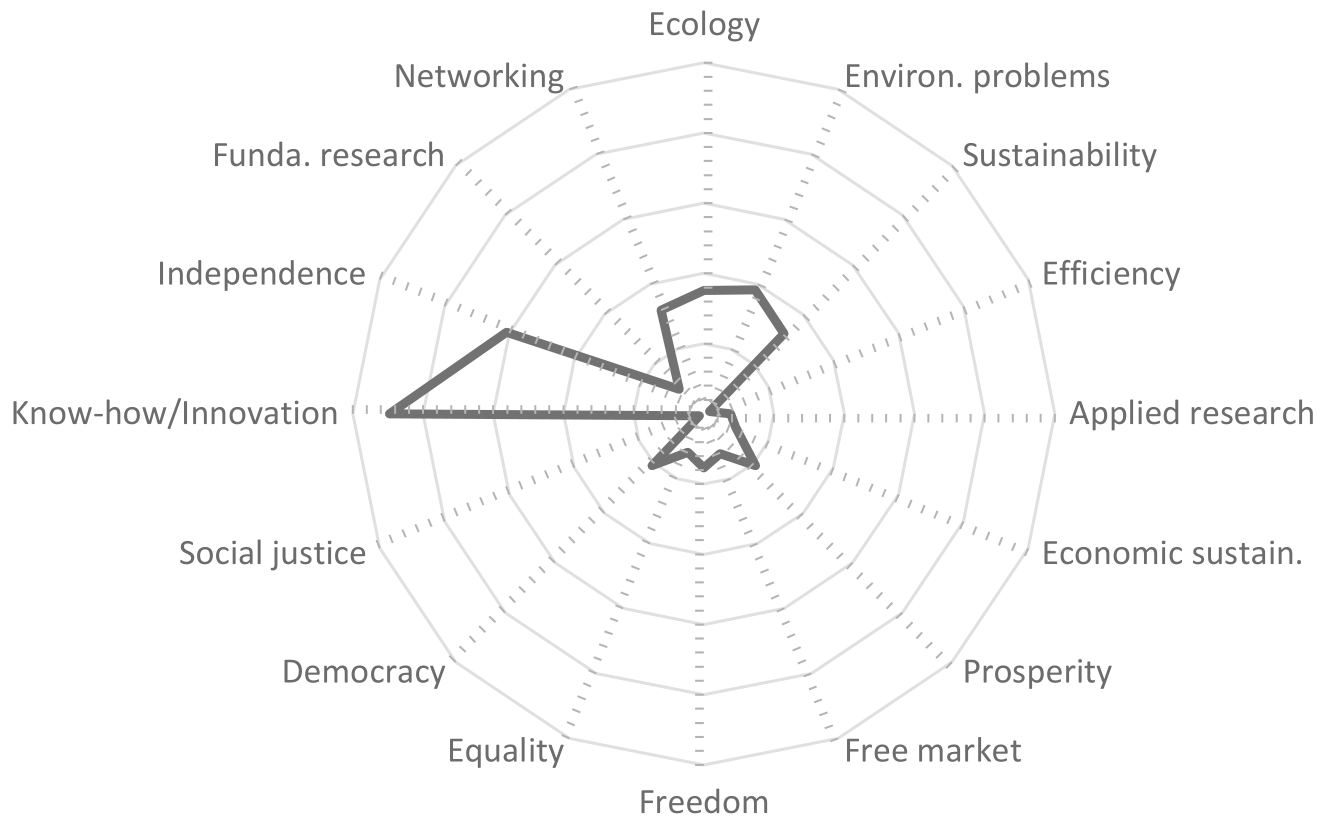

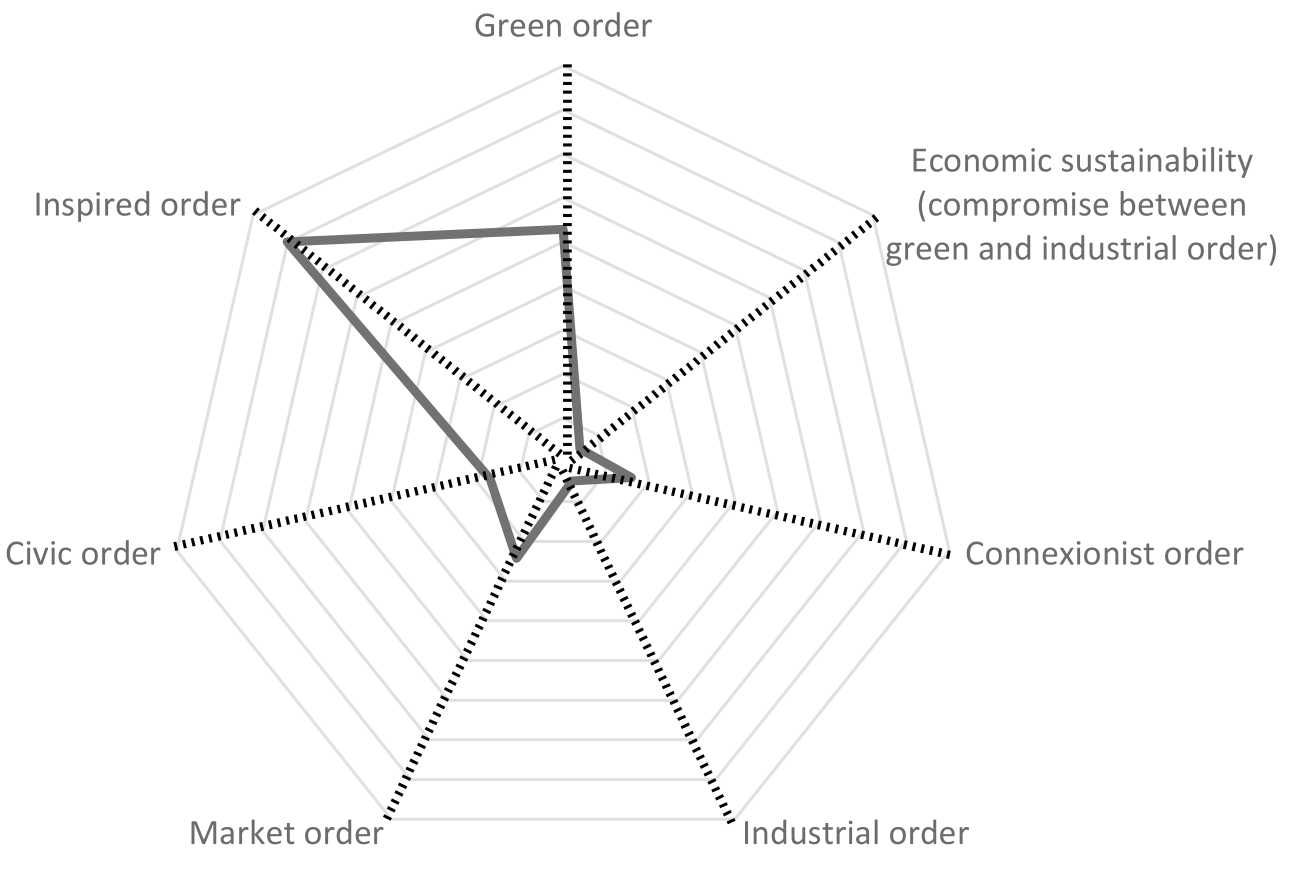

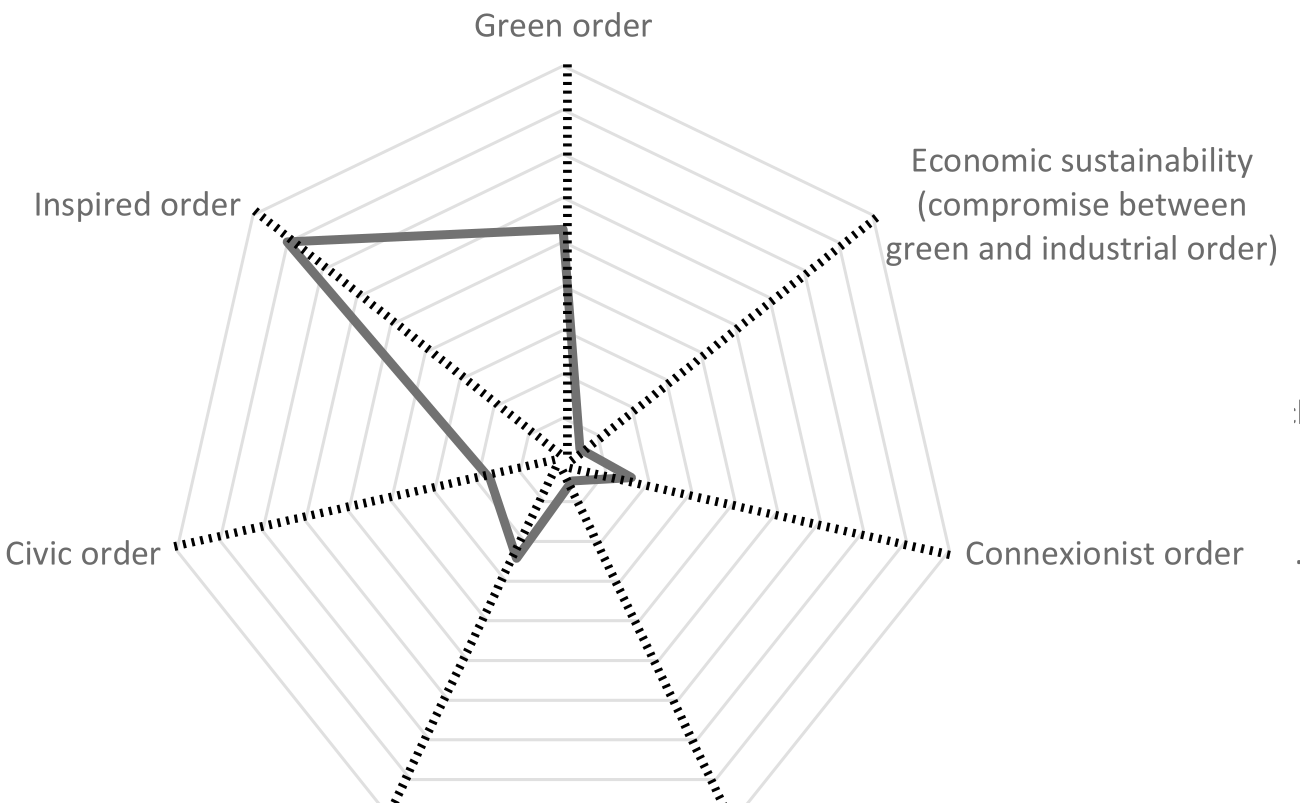

The content analysis of the 59 mission statements illustrates the relative share of each code in relation to all identified codes (see Figure 2 ) and the relative share of a specific order of worth in relation to all orders of worth mentioned (see Figure 3 ) [cf. Kern and Nam, 2013 ]. By doing so, the results highlight the “relative emphasis” of the codes and the orders of worth in the field of scientific policy advice in France [Weber, 2005 , p. 241]. At last, Figure 4 shows the number of orders of worth mentioned in the mission statements to illustrate how and to what extent the think tanks as hybrid organizations combine different logics in their expertise.

Regarding the emphasis of the single codes in the mission statements (see Figure 2 ), “Know-how/Innovation” accounts for the biggest share of all codes. By emphasizing their skills and their innovative approaches, the think tanks demonstrate their technical knowledge for providing reliable knowledge and for applying scientific methods as the basis of their expertise. Accordingly, the emphasis on “independence” underlines, that the expertise is not biased and relies only on scientific standards. In this view, “independence” is closely related to “universalism” as a core value of science [cf. Merton, 1968 , pp. 607–610].

“Ecology”, “environmental problems” and “sustainability” are codes that also occur frequently in the mission statements. Their emphasis shows a moderate commitment to ecological thinking on the part of the think tanks in the field. Nonetheless, it is surprising that “sustainability” holds only a mediocre share (8.08%) in spite of being an “ubiquitous” term that has spread globally and occurs in different settings [Caradonna, 2016 , pp. 1–3; cf. Neckel, 2017 , p. 46].

The appearance of “networking” is expectable in view of the think tanks’ role as hybrid organizations; nevertheless it is emphasized less strongly (7.98%), as if it were a crucial characteristic. The mission statements also mention other codes as guiding principles for the work of think tanks, e.g. “prosperity”, “democracy”, “freedom”, “free market economy” etc., though not to a significant extent. For interpreting the meaning and the emphasis of these codes, the orders of worth offer a fruitful analytical framework.

Figure 3 illustrates the relative share of each order of worth represented in the think tanks’ mission statements. 11 The inspired order dominates the field of scientific policy advice in France with a share of 40.08%, followed by the green order with 26.44%. The market order accounts for 12.12% of the legitimations in the mission statements of the think tanks, the civic order for 8.52% and the connexionist order for 7.98%. The industrial order (2.36%) plays a marginal role only, but it is also partly present in the code “economic sustainability” that forms a compromise between the industrial and the green order of worth [Blok, 2013 , p. 500]. “Economic sustainability” as a compromise is itself used only rarely in the missions statements for legitimizing the work of the think tanks and for qualifying their work (2.43%).

The marginal share of “economic sustainability” as the only identified compromise between two orders of worth is remarkable because it bridges the gap between two separate perspectives in environmental and energy policies. Generally, “economic sustainability” is part of a way of thinking that seeks to change the ways of producing and consuming towards an “economy that runs on renewable energy and does not support growth that would impair the ability of humans and other organisms to live in perpetuity on the Earth” [Caradonna, 2016 , p. 5]. This idea does not gain much attention in the field of scientific policy advice in France and is not applied by the think tanks to legitimate themselves.

The inspired order of worth provides the most comprehensive applied repertoire for the legitimation of think tanks in the field. By referring to the inspired order of worth, think tanks in France follow the tradition of assessing scientific skills as a fundamental element of public administration and as part of the training of government officials [Münch, 2000 , p. 323]. By emphasizing their skills and the independence of their expertise, the think tanks present themselves as competent, unbiased and creative experts for advising public policy in questions of environmental and energy policies. These aspects also fit to the traditional role of think tanks in France as knowledge providers for politics [cf. Münch, 1996 , p. 213].

It is not surprising that the green order of worth is also relevant in this field of scientific policy advice, though not dominant. Instead of becoming a “masterframe” [Eder, 1996 , p. 204] or an “ideal” [Neckel, 2017 , pp. 46–47] for organizations and society, ecology and sustainability are applied as criteria for legitimating think tanks and their expertise on a medium level only. The more moderate relevance of the green order of worth might be ascribed to the rather weak representation of ecological thinking in French politics.

The emphasis of the market order of worth is moderate in the field. Stimulating competition and prosperity as well as fostering freedom are not among the principles think tanks use frequently to legitimate themselves and their work. Consequently, compromises including the market order of worth, such as “green capitalism” [Neckel, 2017 , p. 50] or other visions have not yet entered this field of scientific policy advice.

The connexionist order is only infrequently used for qualifying the expertise and for gaining legitimacy. Activities such as assembling experts or building networks between different spheres do not receive that much attention in the mission statements, even though think tanks as hybrid organizations participate in different spheres and (supposedly) mediate between them.

Furthermore, the think tanks refer not very frequently to the civic order of worth in their mission statements. The relative low emphases of equality, social justice and democracy indicate a separation between environmental and energy issues on the one side and social questions on the other side. The marginal relevance of the civic order of worth goes hand in hand with the dominance of the inspired order of worth with its emphasis on independence and unbiased expertise.

The analysis does not only capture the field level, it also explores how and to what degree think tanks refer to different logics (see Figure 4 ). This allows us to discover the predominant combinations in think tanks’ expertise and provides insights into the way think tanks mediate between different logics.

Figure 4 shows that 18.6% (N=11) of the think tanks refer to only one order of worth in their mission statement. This slightly contradicts the notion of think tanks as hybrid organizations mediating between different logics and spheres. Most of these organizations use the inspired (N=6) or the green order (N=4) to qualify their expertise.

44.1% (N=26) of the mission statements mention two orders of worth. Combining the inspired and the green order (N=10) is the most frequent case, followed by the combinations of the inspired and the market order (N=5), the inspired and the connexionist order (N=4), and the inspired and the civic order (N=3). 12 The combination of the inspired and the green, in addition to another order, is also dominant in mission statements referring to three orders of worth (10 out of 18 cases). 13 According to these findings, a significant share of think tanks communicate that their expertise consists of skilled and unbiased science for supporting environmentalism and helping to solve environmental problems. Besides, other orders of worth are also important for specifying the expertise of the think tanks and for gaining legitimacy (see also Figures 2 and 3 ).

Figure 4 also illustrates that the vast majority of think tanks combine different logics in their mission statements. This is in line with their role as hybrid organizations that mediate between different logics and use their specific expertise to contribute to the process of deliberation in the public sphere as well as to their clients.

5 Conclusion

This study explores the field of scientific policy advice and the role of think tanks in France. The field is characterized by different cultural logics, which comprise different qualities and attributes of the think tanks’ expertise that are crucial for their clients and illustrate some aspects of the role of think tanks in politics and society.

The analysis enables the drawing of conclusions about the autonomy of the field of scientific policy advice in France and the role of think tanks. It shows that the relationship between politics and expertise has changed due to the emergence of new and non-government-funded think tanks. Before, the relationship was characterized as “static” [Campbell and Pedersen, 2015 , p. 689] and “hierarchic” [Münch, 2000 , p. 318]. The purpose of expertise was to provide the state with the means to steer social and technological change [Münch, 1996 , p. 213]. Nowadays, think tanks refer to different cultural logics and emphasize certain qualities of their expertise that go beyond the role of pure “science arbiters” [Pielke, 2007 , p. 2]. 14 By referring to different cultural logics, such as the green order of worth, the market order or the civic order, they position themselves as actors with specific value orientations. This development (at least) partly contradicts Campbell and Pedersen’s [ 2014 , p. 218] conclusion that the relationship between politics and expertise is stable [cf. Münch, 2000 , p. 344].

The results of the analysis indicate a gradual change of the relationship between politics and expertise. On the one hand, the inspired order is the most frequently used justification in the field. By referring to the inspired order of worth, the think tanks emphasize their image as skilled, creative and unbiased experts who provide science-based expertise and information for political decision-making and public deliberation. In this way, the think tanks adapt to the traditional relationship between scientific policy advice and politics in France. On the other hand, by emphasizing, for example, the green order of worth, the think tanks stress that they support environmentalism and are acting (at least partly) as agents in the interest of the environment. By combining the latter with scientific know-how, the think tanks are able to bring environmental issues on to the political agenda and succeed in bridging the gap between politics, science and the demands of the environment. The emphases of the green, the market or the civic order of worth are significant in the field and they are probably a first step towards a stronger politicization of expertise in France.

Furthermore, these results suggest that the think tanks in France are increasingly becoming more independent actors with specific organizational identities. Consequently, the field of scientific policy advice has gained autonomy from politics. These are by no means revolutionary changes, mainly because the institutional constellation of politics and expertise specific to France has shaped and continues to shape the further development of this relationship [cf. Campbell and Pedersen, 2014 , p. 215].

This study also shows how to apply a cultural approach to identify hybrid organizations as well as fields in-between systems through the way they refer to different orders of worth [cf. Thévenot, 2001 ]. By emphasizing several cultural logics, think tanks serve as mediators between different logics and are thus crucial for establishing a new field that connects separate value orientations.

This exploration of the field of scientific policy advice in France is a first step towards the empirical analysis of the intersection of science and politics and think tanks’ expertise. The cultural logics in the field form the basis for further analyses of the communication and the expertise of think tanks. The next step is a comparison of the fields of scientific policy advice of France and Germany to discover possible differences and similarities of the fields depending on their different political systems, civil societies and science systems.

This study also has certain limitations. The use of the orders of worth approach by Boltanski and Thévenot as an analytical framework facilitates future comparisons of the results with other countries. Nonetheless, this deductive approach may conceal some nuances in the organizational identities. A more inductive approach might lead to a more fine-grained picture of the field of scientific policy advice in France. Furthermore, the analysis of the mission statements does not necessarily mirror the actual content of the think tanks’ expertise, because the mission statements might serve only as a façade that is primarily put up to show compliance with legitimate cultural logics in society [Meyer and Rowan, 1977 ]. A future comparative enquiry into the contents of policy briefs is probably a suitable way to analyze the relationship between talk and action more thoroughly.

A List of the think tanks working in the fields of environmental and energy policy in France (with founding year)

B Codes, coding examples and their assignment to the orders of worth

References

-

Albert, S. and Whetten, D. E. (1985). ‘Organizational identity’. Research in Organizational Behavior 7, pp. 263–295.

-

Beck, U. (2003). Risikogesellschaft. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

-

Beckert, J. (2010). ‘How do fields change? The interrelations of institutions, networks and cognition in the dynamics of markets’. Organization Studies 31 (5), pp. 605–627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840610372184 .

-

— (2011). ‘The transcending power of goods: imaginative value in the economy’. In: The worth of goods. Ed. by J. Beckert and P. Aspers. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, pp. 106–128. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199594641.003.0005 .

-

Blok, A. (2013). ‘Pragmatic sociology as political ecology: on the many worths of nature(s)’. European Journal of Social Theory 16 (4), pp. 492–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431013479688 .

-

Boltanski, L. and Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification. Economies of worth. Princeton, NJ, U.S.A. and Oxford, U.K.: Princeton University Press.

-

— (2014). Über die Rechtfertigung. Hamburg, Germany: Hamburger Edition.

-

Boltanski, L. and Thévenot, L. (1999). ‘The sociology of critical capacity’. European Journal of Social Theory 2 (3), pp. 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/136843199002003010 .

-

Boucher, S. and Royo, M. (2009). Les think tanks. Cerveaux de la guerre des idées. Paris, France: Éditions du Félin.

-

Campbell, J. L. and Pedersen, O. K. (2014). The national origins of policy ideas. Princeton, NJ, U.S.A. and Oxford, U.K.: Princeton University Press.

-

Campbell, J. L. and Pedersen, O. K. (2015). ‘Policy ideas, knowledge regimes and comparative political economy’. Socio-Economic Review 13 (4), pp. 679–701. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwv004 .

-

Caradonna, J. L. (2016). Sustainability. Oxford, U.K. and New York, NY, U.S.A.: Oxford University Press.

-

Collins, H. and Evans, R. (2017). Why democracies need science. Cambridge, U.K. and Malden, MA, U.S.A.: Polity.

-

de Montbrial, T. and Gomart, T. (2014). ‘Think tanks à la française’. Le Débat 181 (4), pp. 61–76. https://doi.org/10.3917/deba.181.0061 .

-

Desmoulins, L. (2000). ‘French public policy research institutes and their political impact as another illustration of French exceptionalism’. In: Think tanks & civil societies. Ed. by J. G. McGann and K. Weaver. New Brunswick, NJ and New York, NY, U.S.A.: Transaction Publishers, pp. 139–167.

-

Desmoulins, L. (2009). ‘Profits symboliques et identité(s): les think tanks entre affirmation et dénégation’. Quaderni (70), pp. 11–27. https://doi.org/10.4000/quaderni.503 .

-

Diaz-Bone, R. (2013). ‘Discourse conventions in the construction of wine qualities in the wine market’. Economic Sociology: the European Electronic Newsletter 14, pp. 46–53. URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/156009 .

-

— (2015). Die “Economie des conventions”. Grundlagen und Entwicklung der neueren französischen Wirtschaftssoziologie. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer VS.

-

Eder, K. (1996). ‘The institutionalisation of environmentalism: ecological discourse and the second transformation of the public sphere’. In: Risk, environment and modernity: towards a new ecology. Ed. by S. Lash, B. Szerszynski and B. Wynne. London, U.K., Thousand Oaks, CA, U.S.A. and New Delhi, India: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 203–223. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446221983.n10 .

-

Fligstein, N. (1996). ‘Markets as politics: a political-cultural approach to market institutions’. American Sociological Review 61 (4), p. 656. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096398 .

-

Fligstein, N. and McAdam, D. (2011). ‘Toward a general theory of strategic action fields’. Sociological Theory 29 (1), pp. 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01385.x .

-

Gioia, D. A., Patvardhan, S. D., Hamilton, A. L. and Corley, K. G. (2013). ‘Organizational identity formation and change’. The Academy of Management Annals 7 (1), pp. 123–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2013.762225 .

-

Grundmann, R. and Stehr, N. (2012). The power of scientific knowledge. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139137003 .

-

Hoffman, A. J. (2001). ‘Linking organizational and field-level analyses’. Organization & Environment 14 (2), pp. 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026601142001 .

-

Huyghe, F.-B. (2013). Think tanks. Quand les idées changent vraiement le monde. Paris, France: Maynard-Vuibert.

-

Jasanoff, S. (1990). The Fifth Branch. Science Advisers as Policymakers. Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.: Harvard University Press.

-

Kern, T. and Nam, S.-H. (2013). ‘From ‘corruption’ to ‘democracy’: cultural values, mobilization and the collective identity of the occupy movement’. Journal of Civil Society 9 (2), pp. 196–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2013.788933 .

-

Kosmützky, A. and Krücken, G. (2015). ‘Sameness and difference. Analyzing institutional and organizational specificities of universities through mission statements’. International Studies of Management & Organization 45 (2), pp. 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2015.1006013 .

-

Kühl, S. (2016). Organizations. A systems approach. New York, NY, U.S.A. and London, U.K.: Routledge.

-

Laux, T. (2018). The cultural logics in the field of scientific policy advice in France. Analyzing the justifications in the organizational identity of think tanks . FMSH-WP-2018-139. URL: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01960054 .

-

Lepsius, M. R. (2017). Max Weber and institutional theory. Basel, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44708-7 .

-

Mair, J., Mayer, J. and Lutz, E. (2015). ‘Navigating institutional plurality: organizational governance in hybrid organizations’. Organization Studies 36 (6), pp. 713–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615580007 .

-

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt, Austria. URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 .

-

McGann, J. G. (2016). 2015 global go to think tank index report . TTCSP global go to think tank index reports. Paper 10.

-

Medvetz, T. (2012a). Think tanks in America. Chicago, IL, U.S.A. and London, U.K.: The University of Chicago Press.

-

Medvetz, T. (2012b). ‘Murky power: “think tanks” as boundary organizations’. Research in the Sociology of Organizations 34, pp. 113–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/s0733-558x(2012)0000034007 .

-

Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Free Press.

-

Meyer, J. W. and Rowan, B. (1977). ‘Institutionalized organizations: formal structure as myth and ceremony’. American Journal of Sociology 83 (2), pp. 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550 .

-

Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur de la recherche et de l’innovation (2017). Acteurs de la recherche . Paris, France. URL: http://www.enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr/pid24575-cid49677/principaux-etablissements-publics-de-recherche-et-d-enseignement-superieur.html .

-

Münch, R. (1996). Risikopolitik. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp.

-

— (2000). ‘Kulturen der Demokratie: Historische Gestaltung and aktuelle Herausforderungen’. In: Regulative Demokratie. Ed. by R. Münch and C. Lahusen. Frankfurt, Germany and New York, NY, U.S.A.: Campus, pp. 297–397.

-

Murswieck, A. (2006). ‘Politikberatung in Frankreich’. In: Handbuch Politikberatung. Ed. by S. Falk, D. Rehfeld, A. Römmele and M. Thunert. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag, pp. 590–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90052-0_52 .

-

Neckel, S. (2017). ‘The sustainability society: a sociological perspective’. Culture, Practice & Europeanization 2 (2), pp. 46–52.

-

Neidhardt, F. (2010). ‘Funktionen politischer Öffentlichkeiten’. Forschungsjournal Neue Soziale Bewegungen 3, pp. 26–34.

-

Nowotny, H., Scott, P. and Gibbons, M. (2002). Re-thinking science. Cambridge, U.K.: Polity.

-

Oreskes, N. and Conway, E. (2010). Merchants of doubt: how a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Bloomsbury Press.

-

Pfadenhauer, M. (2010). ‘Der Experte’. In: Diven, Hacker, Spekulanten. Ed. by S. Moebius and A. Schroer. Frankfurt, Germany: Suhrkamp, pp. 98–107.

-

Philipps, A. (2013). ‘Mission statements and self-descriptions of German extra-university research institutes: a qualitative content analysis’. Science and Public Policy 40 (5), pp. 686–697. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/sct024 .

-

Pielke, R. A. J. (2007). The Honest Broker. Cambridge, U.S.A.: Cambridge University Press.

-

Rich, A. (2004). Think tanks, public policy and the politics of expertise. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511509889 .

-

Schimank, U. (2015). ‘Modernity as a functionally differentiated capitalist society: a general theoretical model’. European Journal of Social Theory 18 (4), pp. 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431014543618 .

-

Schmid, L. (2018). ‘Le contre-pouvoir écologique’. Esprit 1, pp. 35–45. https://doi.org/10.3917/espri.1801.0035 .

-

Schützeichel, R. (2008). ‘Beratung, Politikberatung, wissenschaftliche Politikberatung’. In: Politikberatung. Ed. by S. Bröckel and R. Schützeichel. Stuttgart, Germany: Lucius & Lucius, pp. 5–32.

-

Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA, U.S.A., London, U.K. and New Delhi, India: Sage.

-

Stehr, N. (1994). Knowledge societies. London, U.K.: Sage.

-

Stone, D. (1996). Capturing the political imagination. London, U.K. and Portland, OR, U.S.A.: Frank Cass.

-

— (2013). Knowledge actors and transnational governance. Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Swidler, A. (1986). ‘Culture in action: symbols and strategies’. American Sociological Review 51 (2), pp. 273–286. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095521 .

-

Thévenot, L. (2001). ‘Organized complexity’. European Journal of Social Theory 4 (4), pp. 405–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310122225235 .

-

van Zanten, A. (2013). ‘A good match: appraising worth and estimating quality in school choice’. In: Constructing quality. Ed. by J. Beckert and C. Musselin. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, pp. 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199677573.003.0004 .

-

Weber, K. (2005). ‘A toolkit for analyzing corporate cultural toolkits’. Poetics 33 (3-4), pp. 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2005.09.011 .

-

Weingart, P. (2006). ‘Wissenschaftliche Politikberatung aus der Perspektive der Wissens(chaft)soziologie’. In: Handbuch Politikberatung. Ed. by S. Falk, D. Rehfeld, A. Römmele and M. Thunert. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag, pp. 35–44.

-

White, H. C. (1981). ‘Where do markets come from?’ American Journal of Sociology 87 (3), pp. 517–547. https://doi.org/10.1086/227495 .

Author

Thomas Laux works as a post-doctoral research fellow in sociology at the University of Bamberg at the Chair of Sociology, especially Sociological Theory. He obtained his PhD in 2015 from the University of Heidelberg. His research focusses on political sociology, especially civil society and social movements, as well as on cultural sociology. E-mail: thomas.laux@uni-bamberg.de .

Endnotes

1 This article is modified version of a published working paper [see Laux, 2018 ]. The study was conducted while staying at the Collège d’études mondiales at the FMSH in Paris between August and October 2017. I am very grateful that the Collège d’études mondiales and the programme “Changing Societies — New Frameworks for Societal Policies and Decision Making” by the Berlin Social Science Center financially supported my research stay. I want to thank Dominique Méda, Gwenaelle Lieppe, Oliver Bouin and Lisa Crinon for making my stay possible. I also like to thank Dominique Méda, Insa Pruisken, Brigitte Münzel and Leoni Senger for their valuable comments to the manuscript as well as Eva Gassen for helping me with the investigation of the think tanks and for her contribution to the content analysis.

2 This refers to a relational perspective on expetise. The focus of this study is on the qualities of expertise that originate from the relation of its producers, because they observe each other [White, 1981 , p. 518]. Another relational perspective on expertise captures the qualities of expertise as a product of the relation between its producers and its clients (as laymen) [Pfadenhauer, 2010 , p. 106].

3 This role of think tanks corresponds with Pielke’s model of “science arbiters” [Pielke, 2007 , p. 2].

4 For example Rich [ 2004 , p. 11] defines think tanks “as independent, non-interest-based, non-profit organizations that produce and principally rely on expertise and ideas to obtain, support and influence the policymaking process”.

5 Scientifically based expertise implies that the think tanks apply scientific methods [Schützeichel, 2008 , p. 15].

6 Due to the functional differentiation of modern societies organizations refer to several and inconsistent value orientations. Nonetheless, these value orientations do not operate on same level. One of them defines the primary orientation of the organization, while the others represent merely “secondary constraint[s]” [Schimank, 2015 , p. 426].

7 Boltanski and Thévenot [ 2006 ] also identified “the domestic world” and “the world of renown”, but these are not relevant for our analysis.

8 The language of the mission statements is either French or English. The case selection is based upon numerous publications about think tanks in France [e.g. Boucher and Royo, 2009 ; Huyghe, 2013 ; McGann, 2016 ; Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur de la recherche et de l’innovation, 2017 ] as well as the advice of field experts. Nevertheless, it is possible that the study does not cover all the relevant think tanks working in this field.

9 “The measure of emphasis is the pervasiveness with which an element was used throughout a document” [Weber, 2005 , p. 241].

10 Diaz-Bone [ 2015 , pp. 152–153] systemized the orders of worth so as to apply them to the analysis of markets and fields. Following this systematization, the codes identified in the analysis rest upon the guiding principles of the orders of worth and the qualities that are typical of their products.

11 “The world of renown” and “the domestic world” are not visible in the mission statements of the think tanks in environmental and energy policies in France.

12 The other combinations only appear once.

13 Other combinations are only marginal in mission statements mentioning three orders of worth.

14 “Science arbiters” provide information as well as expertise for answering specific questions, but they refuse to deal with normative questions or political concerns [Pielke, 2007 , p. 16].