The COVID-19 pandemic thrust public health officials into the spotlight, as they were called on to communicate regularly and repeatedly about the status, prevention, and treatment of the virus. Their role as high-profile science communicators as well as public health leaders thus became unusually pronounced. COVID-19 communication by public health officials warrants careful analysis because of its importance in communicating rapidly-changing scientific information and public health guidelines to citizens in clear and trustworthy ways. Here, we contribute to this research through a rhetorical case study of public health updates delivered by Dr. Bonnie Henry, British Columbia, Canada’s acclaimed Provincial Health Officer, during the first ten months of the pandemic in BC. Similarly to the situations addressed by numerous public health officials around the world, Henry’s COVID-19 updates addressed a complex set of exigencies: the need to provide accurate and accessible scientific information to British Columbians, the responsibility for issuing public health guidelines, and the ability to persuade citizens to follow them. In this paper, we focus specifically on the role of the first-person plural pronoun “we” in constructing a multi-faceted relational ethos [Condit, 2019] for Henry that negotiates the hybrid identities of scientific expert, authoritative regulator, and motivational community leader. Our rhetorical analysis shows how this occurs through the shifting and ambiguous ways in which “we” communicates a sense of communal togetherness when used inclusively to refer to all British Columbians but also rhetorically reinforces a hierarchical separation between BC’s public health experts and citizens when used exclusively to refer to public health authorities. Examining the specific meanings and functions of “we” within Henry’s COVID-19 communication can help science and health communication researchers as well as practitioners better understand both the powerful and potentially problematic roles that this small but significant word can play in fostering relations of trust and identification with public audiences.

Our theoretical approach integrates research on the importance of public trust in experts and public officials during crises with the rhetorical concept of ethos and socio-linguistic research on the ambiguous meanings and functions of first-person plural pronouns. We begin by reviewing this approach before introducing our case study in more detail, explaining our method, and presenting our rhetorical analysis of the primary meanings and functions of “we” in Henry’s COVID-19 communication. We close by reflecting on the diverse and ambivalent ways in which this small but significant linguistic device contributes to Henry’s relational ethos and on the relevance of our study for the fields of public health and science communication.

1 Theoretical framework

1.1 Trust in science and risk communication research

The importance of communicating in ways that foster relationships of trust between citizens and experts, especially during times of crisis, is well-established within the fields of science and risk communication [Siegrist, 2019; Siegrist & Zingg, 2014]. Trust is a key factor in determining public perception of risk and compliance with public health measures, especially in contexts of high uncertainty [Hunt, Wald, Dahlstrom & Qu, 2018; Siegrist & Cvetkovich, 2000; Siegrist & Zingg, 2014]. In general, science and risk communication frameworks outline elements such as empathy, expertise, competence, integrity, goodwill, and dedication as crucial elements for demonstrating the communicator’s trustworthiness [Besley, Lee & Pressgrove, 2020; Reynolds & Quinn, 2008; Mihelj, Kondor & Štětka, 2022].

Survey research conducted during the early stages of the pandemic confirmed that public trust in science and politicians was an important predictor for accepting COVID-19 public health measures in Germany [Dohle, Wingen & Schreiber, 2020]. Mihelj et al. [2022]’s study showed the importance of political independence in shaping public perceptions of experts’ trustworthiness within newer Western democracies. In Canada, a May 2020 survey showed that citizens considered public health officials the most trustworthy source for accurate, timely information about the pandemic, with British Columbians indicating the highest level of trust among provinces [Waddell, 2020]. Despite some erosion, Canadian trust in public health officials remained strong throughout the first year of the pandemic [Leger, 2021]. Drawing on Siegrest and Zingg’s [2014] research, Khosravi [2020] found that audiences will better hear and act on COVID-19 public health messaging if they perceive the communicator as aligned with their own values and intentions, and hence trustworthy. Tworek, Beacock and Ojo [2020] claim that effective “democratic” public health communication during the first six months of the pandemic did “more than communicate facts”; it sustained and built community by fostering social trust among citizens, and between governments and publics Bucchi [2021, p. 31]. similarly argues that the pandemic has emphasized the importance of science and crisis communication that builds mutually trusting relationships among citizens, experts, and institutions.

Two recent COVID-19-related experimental studies have explored the role of first-person plural pronouns in fostering relations of trust and community between public health communicators and their intended audiences. Tian, Kim and Solomon [2021] maintain that “the use of first-person plural pronouns within [COVID-19] messages may both reflect and bolster a sense of community and communal orientation to coping” Tu, Chen and Mesler [2021, p. 590]. likewise claim that using the pronoun “we” in COVID-19 messaging can build relationships, foster collective identity, and encourage cooperative behaviour [p. 575].

1.2 Ethos

As rhetorical critics, our approach complements research that investigates public perceptions of experts’ trustworthiness by focusing on the communication techniques that experts use to engender trust in their implied audiences. By contrast with audience reception studies, rhetorical criticism focuses on how situated communicative actions address and, in so doing, constitute audience identities and values [Charland, 1987] as well as the communicator’s identity and values. In this paper, we focus on the role of “we” in the construction of a trustworthy and credible character for Henry in relation to the kind of audience that BC’s public updates simultaneously encouraged and presupposed.

In rhetorical terms, we thus are concerned with the role of “we” in constituting Henry’s ethos as well as developing a better understanding of the ethos of public health and science experts in general. The concept of ethos affords a rich and generative way to think about how public health officials strive to develop relationships of trust with public audiences through their communication practices. Within the Aristotelian tradition, ethos refers to the speaker’s character as constructed by their discourse [Condit, 2019, p. 179]. As Aristotle explains, “Persuasion is achieved by the speaker’s personal character when the speech is so spoken as to make us think him [sic] credible” [Aristotle, 2004, p. 7]. Notably, the proof of ethos was considered especially persuasive in situations that lack certainty or consensus [Ofori, 2019, p. 55], as has clearly been the case throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

The concept of ethos includes three main components: phronêsis, aretê, and eunoia. Phronêsis refers to how the speaker communicates “good sense, practical wisdom, sagacity, expertise, and intelligence” [Smith, 2004, p. 10]. Aretê refers to the speaker’s virtuous nature or “excellence of character” as demonstrated through the speech and as defined by the socio-cultural context [Ofori, 2019, p. 56]. Eunoia refers to the speaker’s expression of goodwill — of friendship and empathy — toward the audience; it is the aspect of ethos that attends most explicitly to cultivating a relationship with the audience [Miller, 2003].

While all three components potentially contribute to generating audience trust and respect for the speaker, Condit’s [2019] study of Anthony Fauci and Thomas Frieden’s public health communication during the 2014–15 Ebola crisis foregrounds the centrality for public health officials’ ethos of attempting to cultivate an empathetic, affiliative relationship with audiences during times of health crisis. Drawing on classical and contemporary rhetorical theory, Condit [2019] proposes a relational concept of ethos “as the activation, rebuilding, or maintenance of relationships among different social positions: publics and institutions” [p. 177]. They argue that in the context of health crises like pandemics, ethos forms an essential “relational pivot” or “bridge” between public health leaders and publics [p. 186]. For Condit, as for us, analysing how specific public health experts construct ethos in this relational sense is important, not because of their rhetorical successes or failures as individuals, but because their communication necessarily enacts an institutional ethos “bound to the positionality of public health officials as scientists-who-direct-public-health-policy.” Whether consciously or not, through their rhetorical enactment of this positionality, public health officials construct socio-politically situated relationships between citizens and health authorities [Condit, 2019, p. 185].

As Beason’s [Beason, 1991] research on “signalled ethos” in business speeches shows, the pronoun “we” may play a subtle but significant role in cultivating a strong relationship with audiences. Beason claims that this pronoun fosters identification or “similitude” with audiences, creating a sense of affiliation and building a sense of community [p. 131]. In their discussion of effective communication practices for science researchers, Varpio [2018] likewise underlines how the pronoun “we” contributes to the writer’s ethos by communicating a sense of mutual identification, cohesion, and community [p. 208]. Similarly, in their study of TED talks, Scotto di Carlo [2014] argues that the use of “we” helps breach the barrier between scientific experts and lay audiences [p. 604] while Luzón [2013] maintains that “we” in science blogs promotes dialogic involvement and enacts a dual author identity of specialist and civic scientist.

1.3 Socio-linguistic research on “We”

The research on “we” reviewed above emphasizes the pronoun’s role in constructing the speaker’s relational ethos by evoking a sense of identification and community. However, socio-linguistic scholarship provides a fuller understanding of the complex and sometimes ambiguous meanings and functions of “we.”

Unlike some languages, English does not differentiate formally between inclusive and exclusive senses of “we” [Harwood, 2005; Scheibman, 2014]. Inclusive “we” refers to both the speaker and the addressee, while exclusive “we” does not include the addressee. For example, in the context of COVID-19 when a public health officer states “we must all follow public health measures,” “we” refers inclusively to both speaker and audience whereas the statement “we are increasing testing capacity” refers exclusively to “we” in public health. Exclusive “we” sometimes designates an individual speaker as in cases of pluralis maiestatis (the “royal we” — e.g., the statement “We are not amused” attributed to Queen Victoria) or pluralis modestiae (author’s plural — e.g., in a single-authored research paper, using “we” to refer to the individual author) and sometimes, in a true-plural sense, designates a group that includes the speaker and others, but not the addressee (as in the above example of “we” in public health) [De Cock, 2016]. Thus, the meanings and functions of “we” in English are inherently heterogeneous, ambiguous, and context-dependent [Du Bois, 2012; Makmillen & Riedlinger, 2021; Scheibman, 2014].

The fuzziness of the exclusive/inclusive divide can be situationally useful and strategically deployed in academic, political, and healthcare contexts. In scholarly writing, authors can use “we” inclusively to index mutual knowledge and construct audience involvement but “we” also may refer exclusively to the author and their potential co-authors or, as noted above, to a single author [Harwood, 2005; De Cock, 2016]. In their study of research articles by Mäori scholars, Makmillen and Riedlinger [2021] have shown how the blurred categories of “we” can extend beyond a basic inclusive/exclusive distinction to include a range of shifting identities and social relations as researchers and community members, thus inviting “multiple identification through ambiguity” [p. 11].

Likewise in political discourse, first-person plural pronouns can foster identification, alignment, and disalignment [Bucholtz & Hall, 2005] and contribute to the construction of subject positions, group relations, and group identity [Downing & Perucha, 2013, p. 380]. Uses of “we” in political discourse may alternate between or ambiguously combine exclusive reference to the speaker’s specific group (e.g. a government institution or political party) and broader inclusive references to a national “we” (i.e. the country and its people). The pronoun can function strategically “as a distancing effect to avoid [or diffuse] responsibility on certain issues” [Downing & Perucha, 2013, p. 388] and it also can suggest “a shared moral stance” between political leaders and public audiences [Bucholtz & Hall, 2005, p. 604]. Citing Billig’s [1995] concept of “banal nationalism,” Proctor and Su [2011] maintain that, precisely because of its “everyday” quality, “we” functions as an unremarkable but important “flag” within a nationalistic register [p. 3252].

Socio-linguistic research on healthcare uses of “we” has focused primarily on doctor-patient communication. In this context, “we” may refer exclusively to the healthcare provider or a healthcare team, communicating distance between provider and patient and indicating that the speaker belongs to a group that the audience does not [Rees & Monrouxe, 2009]. “We” also may refer inclusively to provider and patient, signaling their connection, but inclusive “we” can also obscure power asymmetry and it may permit healthcare providers to feel they are inclusive, when in fact they are not [De Cock, 2016; Rees & Monrouxe, 2009]. De Cock [2016] also discusses a hearer-dominant “we” which refers not to the speaker but, exclusively, to the addressee, as in “How are we feeling today?” This “we” can demonstrate empathy and establish solidarity, but it may also be perceived as condescending or impolite, and as maintaining, rather than diffusing, the relationship’s power asymmetry [De Cock, 2016; Rees & Monrouxe, 2009].

Combining socio-linguistic insights on the pronoun “we” with science and risk communication research on trust and rhetorical theories of ethos provides a generative framework for understanding the complex and ambiguous ways this pronoun may function in fostering relationships between public health officials (or other expert science-risk communicators) and their implied citizen audiences. In the case study analysis that follows, we demonstrate this complexity by exploring the multiple roles that “we” plays in the rhetorical construction of Henry’s ethos during BC’s COVID-19 updates.

2 Case study context

Appointed Provincial Health Officer in 2018, Henry is British Columbia’s senior public health official. Working closely with the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) and drawing on her prior experience in infectious disease management, Henry led the province’s COVID-19 response. At a national level, Canada’s pandemic response and communication were led by the country’s Chief Public Health Officer, Dr. Theresa Tam. However, because healthcare is a provincial jurisdiction in Canada, each province developed its own pandemic plans and communications. In some provinces, political leaders and/or other scientific experts played central roles in official COVID-19 communication. For example, Ontario’s official updates were delivered mainly by the Premier Doug Ford and Health Minister Christine Elliott while the leader of the province’s COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, Dr. Peter Jüni, provided frequent (but less official) media interviews and public health information. In BC, however, Henry acted as the province’s principal communicator throughout the pandemic while Premier John Horgan and Health Minister Adrian Dix played less central communication roles. Under BC’s Public Health Act, Henry also had the authority to declare a public health emergency and issue public health orders [H. Henry & Henry, 2021, p. 108].

Similarly to other provinces, BC’s public-facing communication occurred primarily through regular public updates streamed live by the CTV News channel. For the period of our research (mid-March to end of December 2020), Henry delivered almost daily in-person updates until the end of May, and approximately two to three updates weekly thereafter. Lasting approximately 15 minutes each, these updates typically began with an introduction by Health Minister Dix, followed by Henry’s report on new cases, community outbreaks, and case status by health region.1 After this report, Henry normally talked for an equal, if not greater, amount of time about the civic roles and responsibilities of British Columbians during the pandemic. A media question period occurred after the prepared portion of each update.

Dubbed the “calming voice in a sea of coronavirus madness” [Picard, 2020] and “BC’s Great Communicator” [Smith, 2020], Henry was widely applauded both within and beyond British Columbia for her style of communication [Little, 2020; Marsh, 2020; Picard, 2020; Porter, 2020; Smith, 2020; Tworek et al., 2020]. In their report Democratic health communications during COVID-19, Tworek et al. [2020] describe Henry as “an exceptionally good communicator,” commending her for “being gentle and compassionate, building trust, expecting good faith, and offering clear scientific information in a consistent, understandable, reassuring way” [pp. 60, 17]. For health journalist Picard [2020], Henry’s public briefings comprised “a master class in crisis communication.” During the first months of the pandemic, she became a cultural icon, celebrated on social media, as well as in public art murals, musical tributes, and fashion [Picard, 2020; Hinks, 2020; Wainman, 2020].

Instead of threatening disciplinary enforcement, Henry’s main communication strategy was to encourage citizens to follow public health protocols by ensuring they properly understood “what they need to do and why” and trusting that they would willingly fulfill their “mutual responsibilities” [Porter, 2020]. According to Tworek et al. [2020], BC’s response aimed “to cultivate trust (among citizens as well as between government and public)” to strengthen public solidarity, collaboration, and resilience [p. 59]. As we have argued in our previous study of BC’s COVID-19 communication, the province’s strategy enacted a (neo)communitarian ideology focused on citizens’ civic duty to voluntarily take responsibility for the health of their community [Spoel, Lacelle & Millar, 2021]. In this paper, we investigate more fully the role of the first-person plural within this pro-social rhetoric.2 As Henry herself explained at the 2020 Canadian Science Policy Conference, her communication team consciously decided to use inclusive expressions such as “what we are going through” and “here’s what we can do” to help foster feelings of togetherness and to “drive the altruistic response” [B. Henry, 2020].

3 Method

Our study used the method of rhetorical analysis which, in general, applies rhetorical theory and concepts to specific instances of language use to generate textured insights about the situated forms, meanings, and functions of this language use. The specific instances of language use in our case study consisted of the 131 live-streamed public updates wherein Henry was the primary speaker, delivered between March 16, 2020 and December 31, 2020. This time frame represents (1) the first wave of the pandemic in BC from mid-March to roughly the end of May; (2) the easing of restrictions between June and August; (3) the second wave which began in September, peaked in late November, and decreased modestly during December.

The first-personal plural pronoun usage analysed in this paper is drawn from data collected as part of our larger project examining how BC’s COVID-19 communication during the first parts of the pandemic rhetorically constituted “good” covid citizens. This data consists of manually transcribed excerpts from BC’s public updates which contain content related to pro-social behavior and civic values for how BC citizens should respond to the pandemic as well as to the role of public health officials in guiding this response.

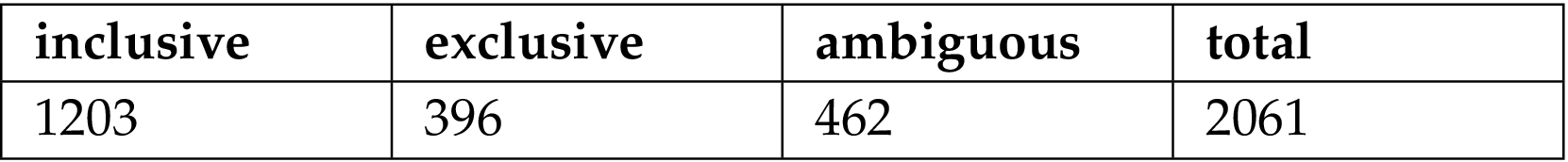

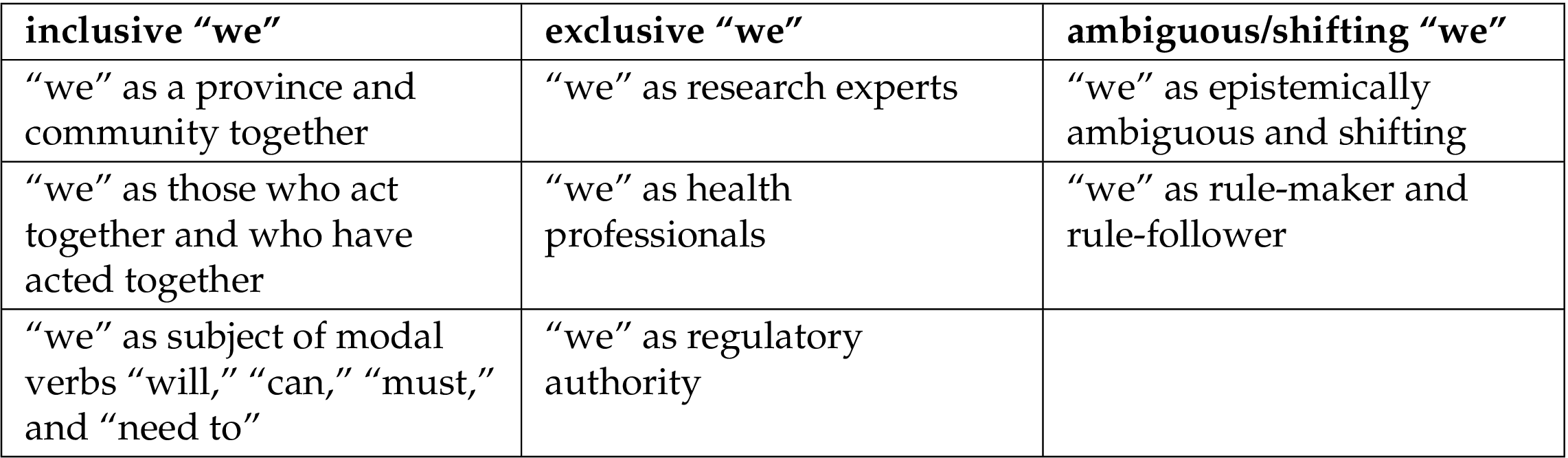

After identifying all uses of “we” through a word search,3 lead author Spoel categorized them into three main types of referent based on their meanings within the context of specific statements: 1. occurrences of inclusive “we” that refer both to Henry (or to Henry and her Public Health team) and to her implied audience; 2. occurrences of exclusive “we” that refer either to Henry and her Public Health team as a group or to Henry singularly, but do not include the audience; and 3. occurrences of ambiguous and/or shifting inclusive and exclusive referents for “we” (see Table 1). Following review by authors Millar and Lacelle the research team collaboratively refined these categorizations. Referents were identified as ambiguous and/or shifting whenever more than one member of the research team considered them such.

Through ongoing team discussion and grouping of “we” statements into separate thematic files in our secure google drive, we iteratively coded each of these main categories into eight sub-themes (see Table 2). Statements that exemplify more than one theme were included in all relevant thematic groupings.

In the following analysis, we provide examples and analysis of each of these main categories and sub-themes of “we” usage and draw on our theoretical framework to discuss their meanings and functions in the rhetorical enactment of Henry’s relational ethos.

4 Analysis

4.1 Inclusive “We”

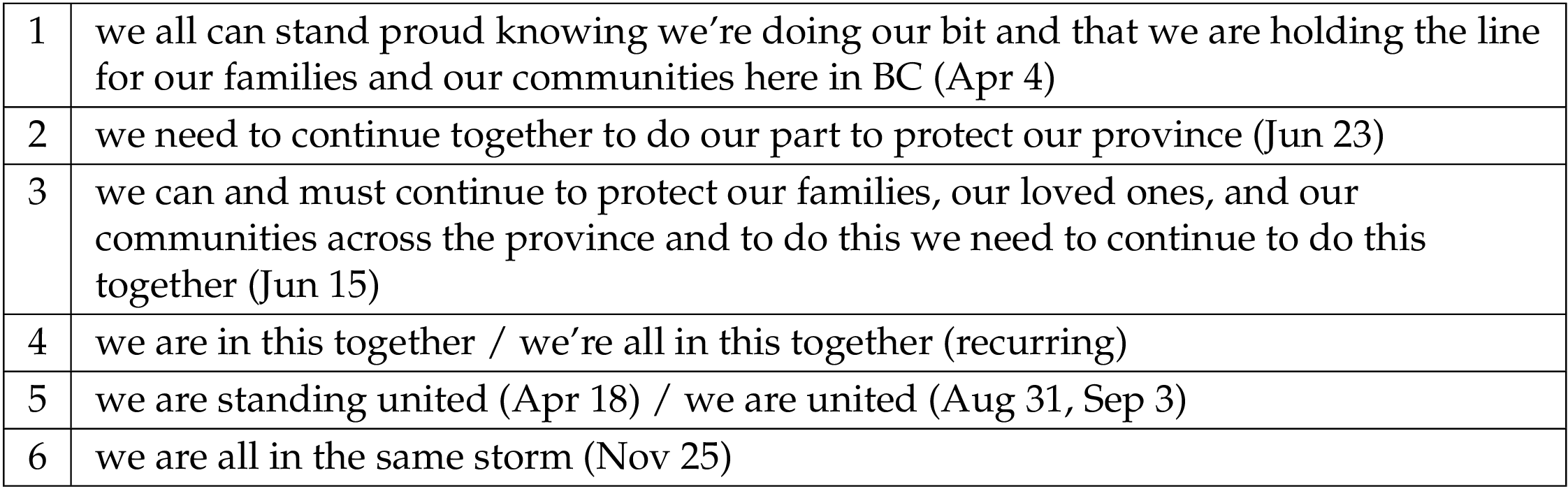

The most obvious and prominent use of “we” in Henry’s discourse is an inclusive type, referring to both speaker and audience. In this primary usage, “we” seems intended to generate a sense of togetherness and solidarity that supports an ethos of communal strength and coping. It evokes Henry’s affiliation with her audience and supports her character as a leader who can bring people together in an empathetic and motivating way. These meanings are reinforced by how the term “we” often occurs in association with the terms “community” or “communities” and “together,” as well as the terms “province” and “BC.”

The excerpts included in Table 3 illustrate how “we” typically refers to all British Columbians. Henry also frequently articulates variations of the ubiquitous COVID-19 slogan “we’re all in this together,” especially in briefings delivered during the first wave (March to June 2020). Using “we” in this way suggests solidarity between Henry and her implied audience, as well as — importantly — among audience members themselves. Consonant with Billig’s [1995] concept of “banal nationalism,” this usage fosters a sense of provincial pride that motivates citizens to “hold the line” against COVID-19.

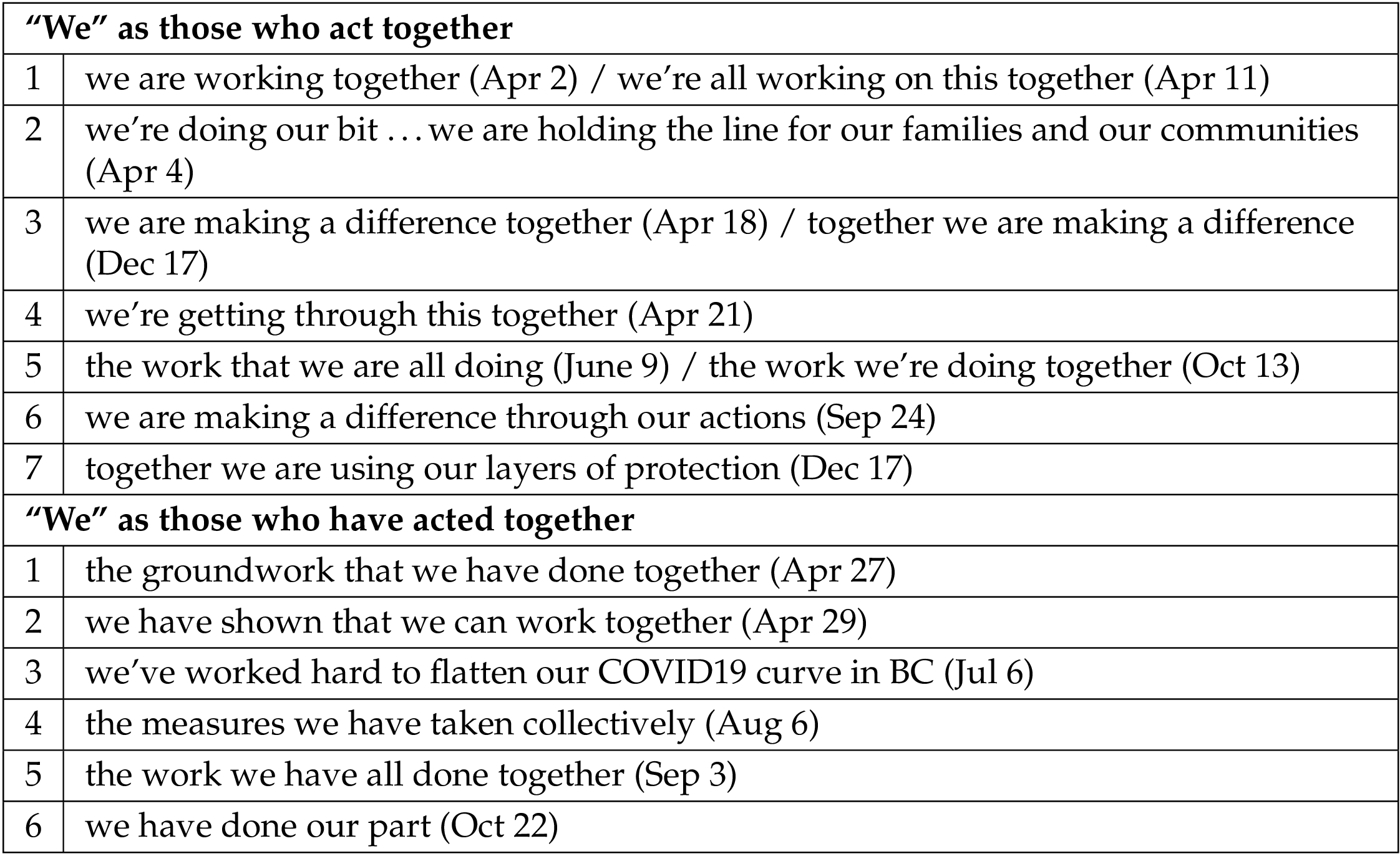

Rather than simply stating a static condition of what “we” are, Henry more often links this communal “we” with action, with what “we” are doing or need to do. These expressions emphasize both the ability and the obligation of “we” to work together and do “our part” for “our province” (see Table 4 below). Linking “we” with verbs and phrases denoting action reinforces a dynamic ethos of communal strength and coping.

Following the initial phase of the province’s pandemic response, Henry also often refers, using the past tense, to what “we” have done (see Table 4). By commending how “we” have acted together in the past, these kinds of statements construct Henry’s ethos as a leader who recognizes and appreciates the efforts of her constituents. References to what “we” have already done also establish a shared history of the community’s ability to do whatever is needed to control the pandemic, with the motivational implication that if “we” have been able to do this in the past, “we” can do it again.

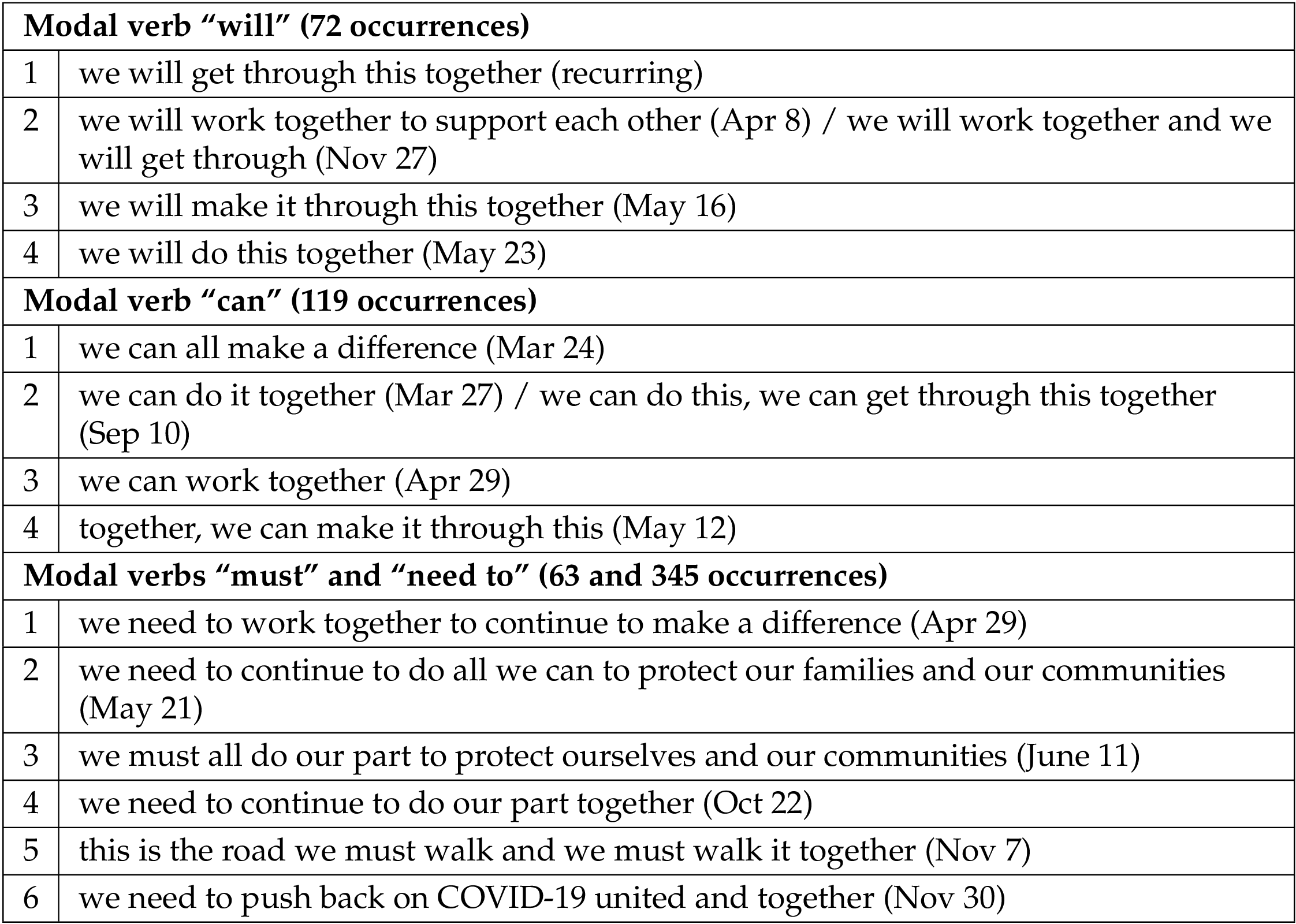

The frequent articulation of “we” with the modal auxiliary verbs “will,” “can,” “must,” and “need to” when describing the actions of British Columbians adds more layers to how inclusive “we” constructs an ethos of communal action and coping (see Table 5 below).

With statements that include the expression “we will” (see Table 5), Henry both presumes and enacts a strong leadership ethos by authoritatively declaring what “we” will do — assuming “we” continue to “work together” and “do our part.” The modal “will” communicates Henry’s judgment of what will likely be the case, rather than the absolute certainty of what is going to occur [Palmer, 2001]. “We will” thus functions as a confidence-building rallying call for the audience to continue complying with public health measures.

In the recurring expression “we can” (see Table 5), the modal “can” functions epistemically to establish what is possible in terms of communal action, as well as dynamically to index the ability of “we” to successfully perform the called-for actions [Palmer, 2001]. Here again, we see how expressions with inclusive “we” function in a highly suasory way, by commending “our” capabilities and asserting Henry’s confidence that collectively “we” are able to do what is needed to successfully navigate the pandemic.

The modals “must” and “need to” occur even more frequently in Henry’s descriptions of the actions “we” do “together,” especially during the second halves of her briefings (see Table 5). Rather than emphasizing what is likely and possible or what “we all” have the ability to do, these modals merge a sense of empirical necessity with moral obligation [Palmer, 2001], thus framing required action as, also, conscientious action [Palmer, 2001; Giltrow, 2005]. These statements address an inclusive “we” whose health and safety requires the community as a whole to “push back on COVID-19 united and together.” They also constitute “we” as a community with an inherent sense of ethical duty to act “together” to “protect our families and communities.”

These various uses of inclusive “we” foreground arête and eunoia by signalling Henry’s empathetic affiliation with her audience, predicated on their shared identity of proud and committed British Columbians who have an inherent pro-social moral disposition motivating them to “work together” on behalf of “our community.” Conversely, the relational ethos that inclusive “we” communicates can also be interpreted as socially distancing. Henry’s authoritative assertions of what “we” are, will, can, and must do index a hierarchical relationship between her position as public health-community leader and the audience’s position as those her discourse seeks to motivate. In a patronizing, hearer-dominant sense [De Cock, 2016], inclusive “we” thus can be seen as encouraging mainly identification among audience members, rather than between Henry and the audience.

4.2 Exclusive “We”

Along with these types of inclusive “we,” an exclusive type of “we” also occurs consistently in Henry’s COVID-19 updates. These instances of “we” are exclusive because they appear to refer to Public Health experts and herself but not to the audience of British Columbians to whom the updates are addressed. Instead of joining speaker and audience, this form of “we” distinguishes Public Health knowledge and actions from those of citizens. Exclusive “we” occurs most frequently in the “facts and figures” portion of the regular public briefings, as well as in longer modeling updates delivered approximately once a month.

Our analysis of exclusive “we” shows several distinct though interconnected meanings. Exclusive “we” may refer to: i) Henry and her Public Health team as scientific experts and researchers; ii) BC’s Public Health professionals as healthcare providers and managers; or iii) Henry singularly as the province’s legally-authorized public health regulator.

4.2.1 “We” as research experts

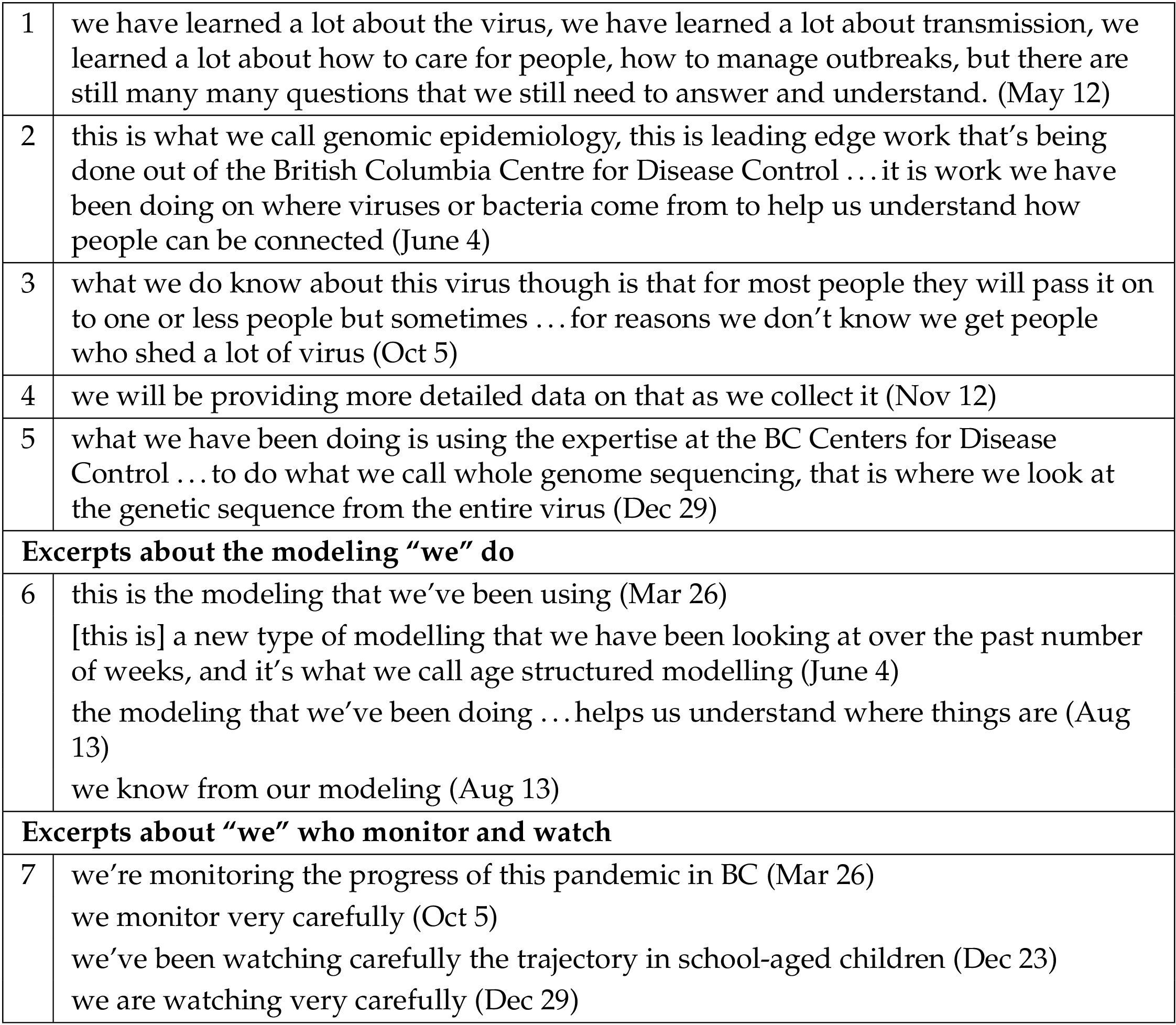

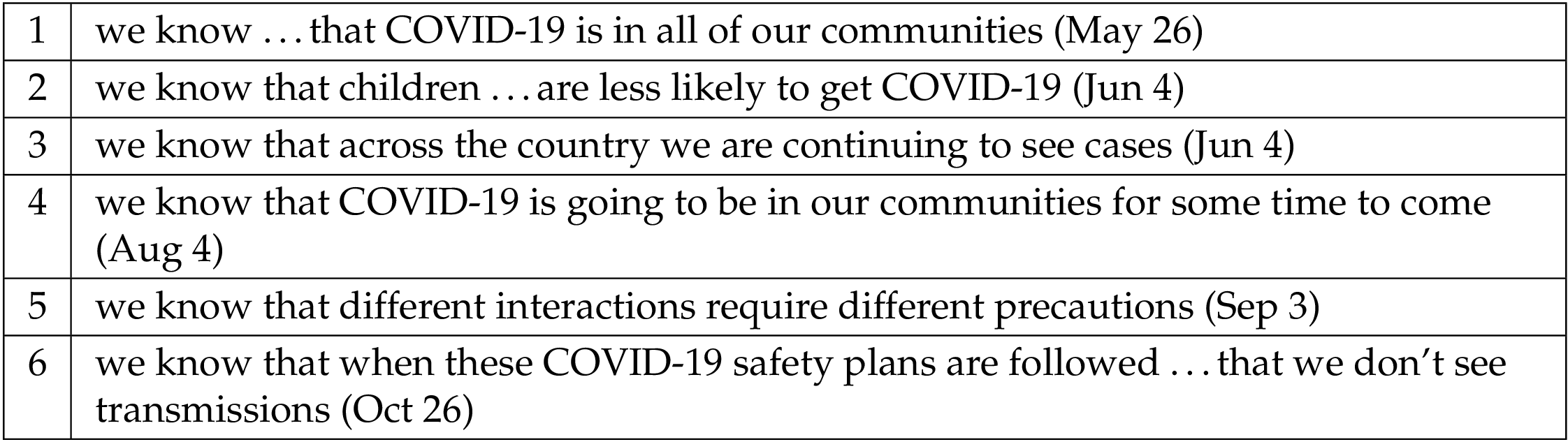

The most obvious uses of exclusive “we” occur in recurring phrases referring to the pandemic-related data and scientific knowledge which Henry presents (see Table 6 below). This usage is especially prominent during the longer data-intensive modeling updates.

Generally, the exclusive “we” of public health expertise occurs in conjunction with verbs pertaining to scientific knowledge and processes, such as “know,” “understand,” “learn”, “monitor,” “watch,” and “collect” (see Table 6). These statements characterize “we” as having specialized knowledge (e.g., concerning genomic sequencing) and as conducting careful and diligent processes of COVID-19 data collection, analysis, and modeling. As well, when used with the verb “learn,” exclusive “we” often highlights the evolving nature of scientific knowledge about the virus, as seen in excerpts 1 and 3 (Table 6). With statements like these, Henry explicitly acknowledges the reality of scientific uncertainty, while also emphasizing the extent of what “we have learned.” These kinds of explanations contribute to her ethos by demonstrating honesty and humility to her audience, as well as a commitment to continuous learning. As a whole, uses of exclusive “we” like those illustrated in Table 6 reinforce both the phronesis and arête of Henry and her Public Health team.

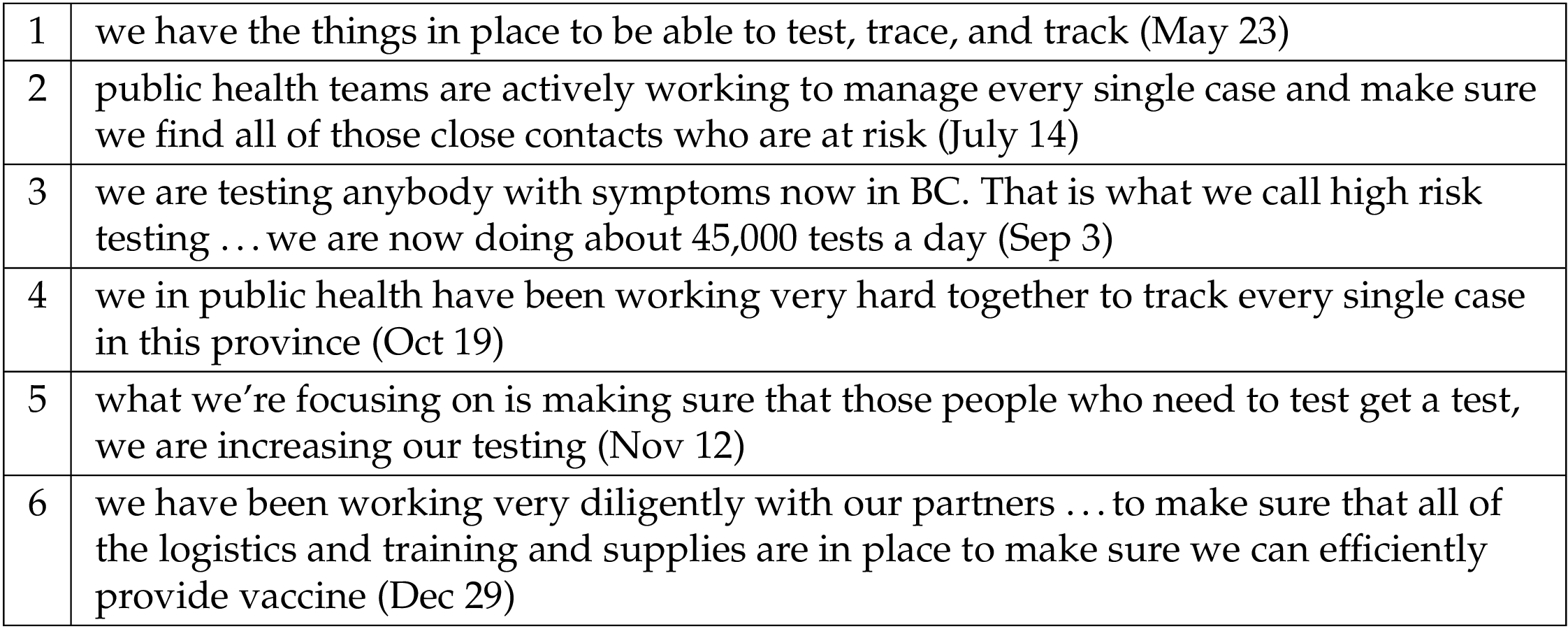

4.2.2 “We” as health professionals

In addition to signifying Public Health experts, exclusive “we” also designates Henry and BC’s Public Health team in their related, but not identical, role as healthcare providers and managers. This identity surfaces most clearly through frequent explanations of what “we” are doing in relation to testing and contact tracing as well as other statements about how Public Health is “managing” the province’s pandemic response (see Table 7). These kinds of statements do more than explain what “we” in Public Health are doing; they demonstrate Henry and her Public Health team’s excellence of character, by emphasizing the virtues of careful, diligent, and responsive work on behalf of the province’s citizens.

4.2.3 “We” as regulator

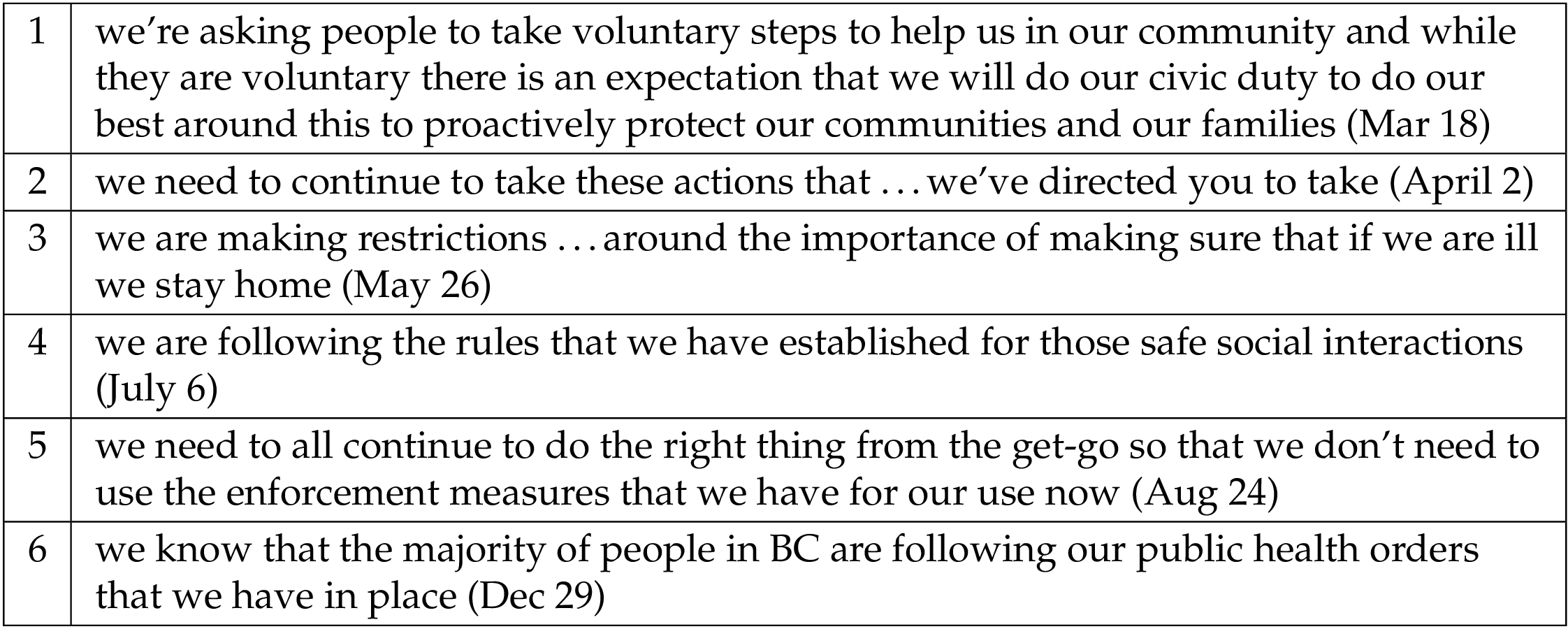

A third type of exclusive “we” foregrounds a legal-political ethos of authoritative governance. This “we” refers to Henry’s identity as the province’s public health regulator with the legal authority to declare public health emergencies and issue orders. Of all uses of exclusive “we,” this “we” constructs the greatest distance and power asymmetry between Henry and her implied public audience.

For example, in excerpt 1 of Table 8 (above), an exclusive “we” issues orders that citizens (“you”) are required to follow. Although the word “voluntary” evokes a non-coercive ideology of social trust and somewhat mitigates the authoritarian character of “we,” the phrase “unless you don’t do what we say” clarifies that what “we say” is, in reality, a non-negotiable regulation. Later in September, Henry’s communicative style similarly justifies and mitigates the imposition of renewed public health regulations when she states that “issuing orders is not something that we do lightly, it is our last resort.” By early November, as the second wave took hold, she reluctantly confirmed that “orders are …what we need to put in place right now” (Nov 9). Here, “we” is characterized as obliged to take action in a way that is not arbitrary but situationally necessary and responsive.

Unlike uses of “we” to refer to the province’s whole Public Health team, when Henry uses “we” with reference to “the measures we have put in place” or to an order “we have issued,” this is best understood as a singular “royal we.” As BC’s Provincial Health Officer, Henry was the individual official who had the authority to issue, as well as rescind, public health measures. Although she occasionally uses “I” in these authoritative statements (see excerpt 1, Table 8), typically she uses “we” when referring to the “putting in” of orders. This diminishes the impoliteness of imposing regulations on citizen behaviour, while also diffusing individual responsibility for the imposition.

4.3 Ambiguous and shifting “We”

Thus far, we have looked at instances where inclusive and exclusive meanings of “we” are fairly easy to distinguish. Additionally, throughout the updates, Henry makes statements which blur the distinction. This occurs both through the inherent ambiguity of specific instances of “we” as well as shifts within single statements of what appears to be, on one hand, an exclusive meaning and, on the other, an inclusive meaning. In this section, we focus on how these shifts and ambiguities occur in relation to the kinds of knowledge and action attributed to Public Health and those attributed to all British Columbians.

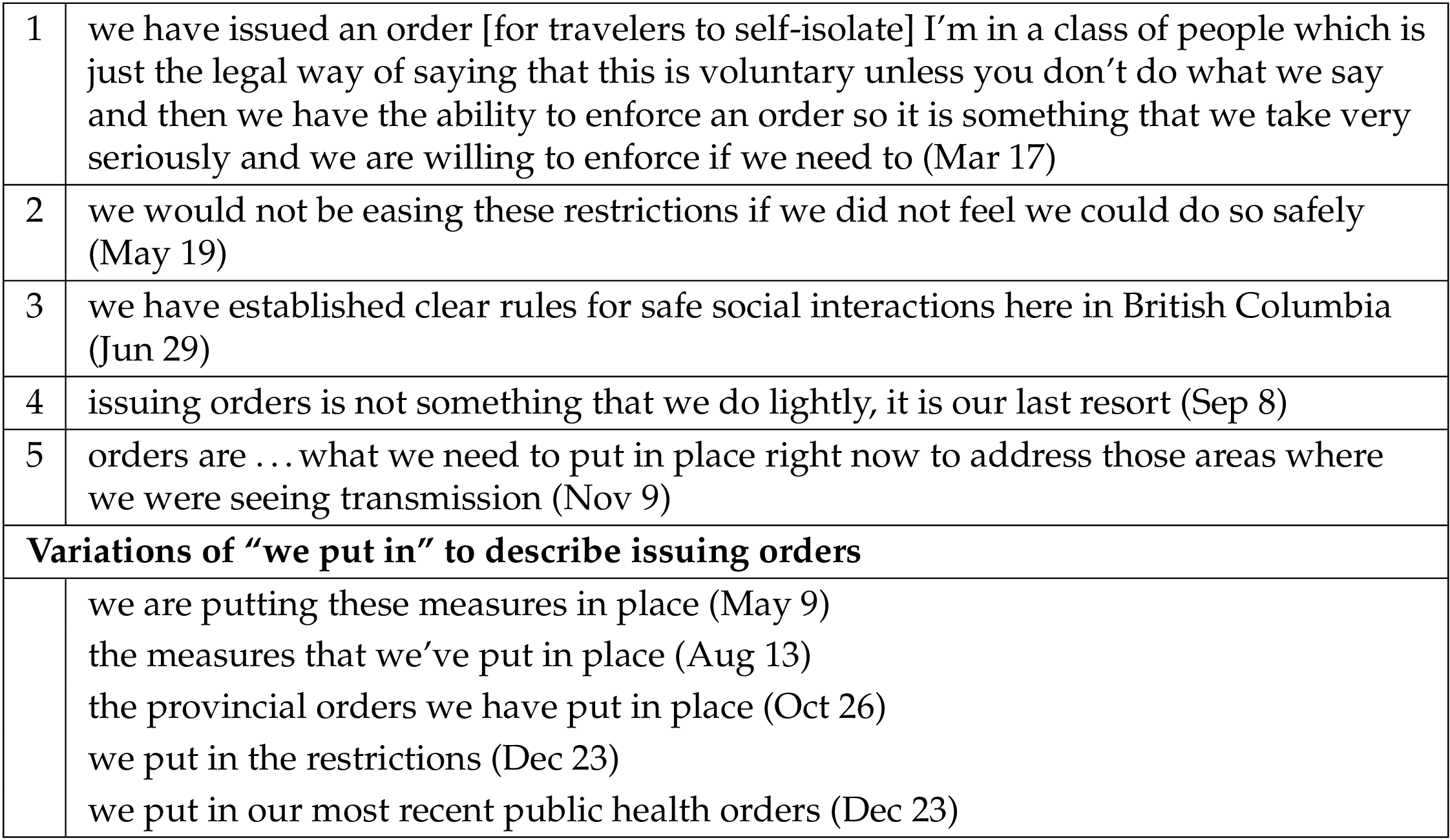

4.3.1 Epistemic ambiguities and shifts

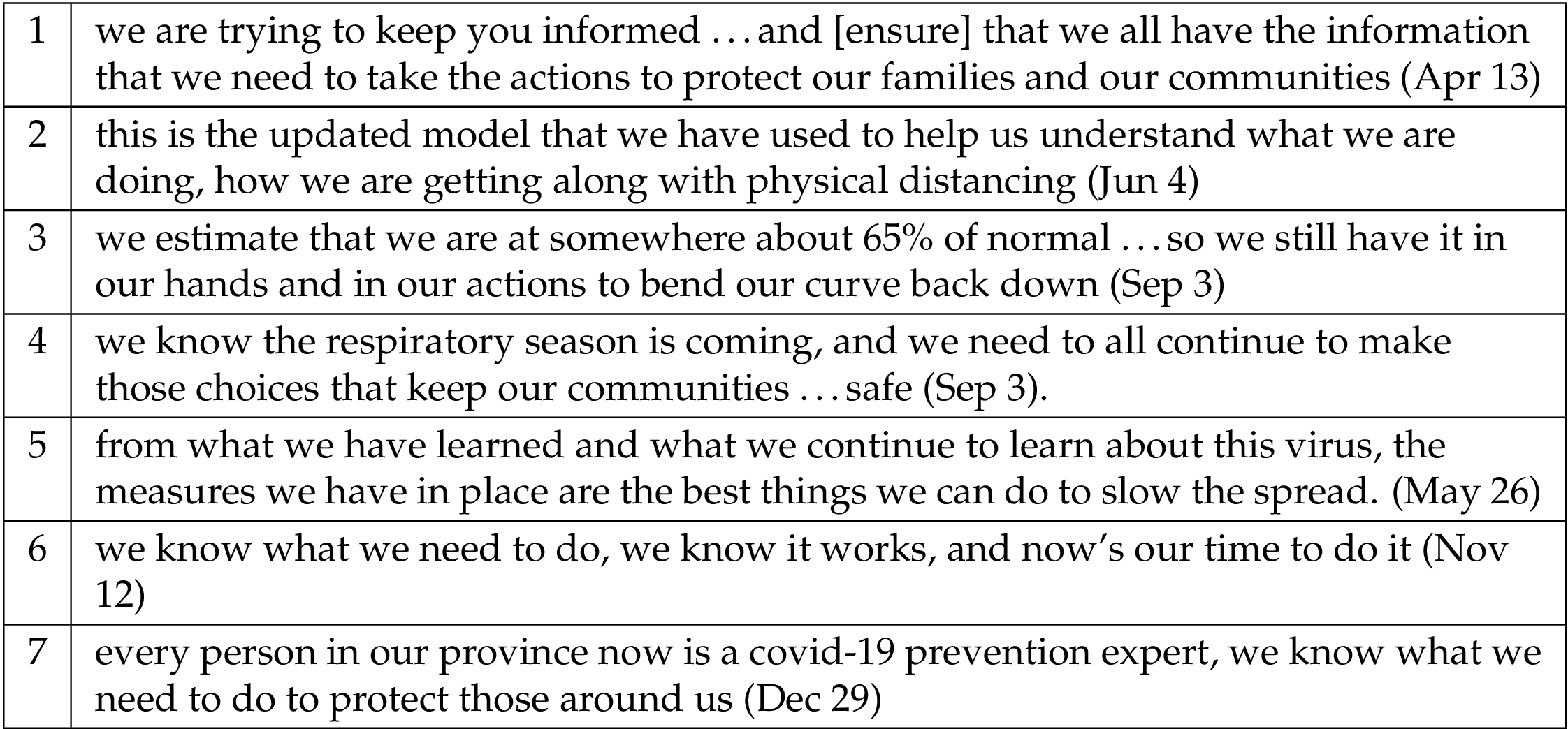

Who “we” refers to when used as the subject of epistemic verbs such as “see,” “look,” “learn,” “understand,” and, especially, “know” is quite often ambiguous. While some occurrences of the frequent collocate “we know” seem to refer exclusively to public health expertise, at other times it is unclear whether Henry is referring to what “we” as experts know or whether she is referring to, and thus claiming, a kind of common knowledge among all British Columbians. For instance, in the excerpts about what “we know” in Table 9 (below), does “we” refer to knowledge possessed by Public Health experts or to what Henry presumes as being common knowledge?

A slightly different blurring takes place within single statements where “we” in one instance quite clearly refers to all British Columbians but in another seems to be more or less exclusive to health experts. In these utterances, inclusive “we” is often associated with either the status or the actions of the provincial community as a whole, whereas ambiguously exclusive/inclusive forms of “we” are associated with knowledge (see Table 10 below).

In excerpts 1–3 (Table 10), the shift between exclusive and inclusive referents is fairly easy to distinguish: “we are trying to keep you informed” is exclusive and “we all have the information that we need” is inclusive; “the updated model that we have used” is exclusive and “how we are getting along” is inclusive; “we estimate” is exclusive and “we still have it in our hands” is inclusive. In these excerpts, the knowledge-making activities of “we” as Public Health experts provide insight on how “we” as British Columbians are faring and reinforce the importance of all British Columbians continuing to take the “actions” recommended or required by Public Health. The asymmetry of this relationship between public health expertise and citizen action is obscured by the use of the same pronoun to refer to both groups.

In other statements, although the “we” who is experiencing the pandemic and taking action seems inclusive, it is more ambiguous whether the “we” who knows is exclusive or inclusive. For instance, in excerpt 4 (Table 10), the “we” who needs to take action (“make those choices”) is clearly inclusive but the “we” who knows that respiratory season is coming could be exclusive or inclusive — is Public Health communicating its expert knowledge to citizens, or is Public Health asserting that this is common knowledge? A similar ambiguity occurs in excerpt 5.

Increasingly during the second wave, the “we” who knows seems to be the same as the inclusive “we” who acts. This occurs most evidently through the recurring phrase “we know what we need to do” (see excerpts 6–7, Table 10). That “we” who “know” are the same as “we” who “do” becomes fully evident with Henry’s statement near the end of December: “Every person in our province now is a COVID-19 prevention expert. We know what we need to do to protect those around us.” This characterization of citizens as “prevention expert[s]” potentially bolsters Henry’s relational ethos because it praises her audience’s knowledge and fosters identification between the exclusive “we” of Public Health experts and the inclusive “we” of all British Columbians. However, the kind of expertise Henry attributes here to citizens is limited to preventive behaviours. As well, linking the claim that “every person” is a “prevention expert” with the statement “we know what we need to do” positions citizens as having both epistemic and behavioural responsibility for managing the pandemic, while implicitly diffusing Public Health responsibility.

4.4 “We” as rule-maker and rule-follower

Our analysis also revealed shifting and ambiguous uses of “we” in statements which combine the exclusive “we” of Public Health in its regulatory (rather than knowledge-making) identity with an inclusive “we” designating those who are expected and required to follow regulations (see Table 11 below).

Excerpt 1 (Table 11) moves between exclusive and inclusive meanings when discussing the “steps” that Public Health expects, though has not yet ordered, citizens to take. The initial “we” refers in an exclusive sense to what Henry and BC’s Public Health authority are asking citizens to do, while the second “we” refers inclusively to what all British Columbians are expected, or being asked (pseudo-voluntarily) to do. The statement “we need to continue to take these actions that …we’ve directed you to take” (excerpt 2) similarly shifts between the communal “we” of all British Columbians who take actions and the exclusive, regulatory “we” who issues directives to the communal “we.” The other excerpts in Table 11 likewise ambiguously combine an exclusive regulatory “we” with an inclusive regulated “we.”

Though logically disconcerting, using the same pronoun to refer to those who regulate and those who are regulated blurs the contrast and power asymmetry between these two groups, giving the impression that the “we” who makes rules and the “we” who follows rules are one and the same. It draws attention away from Henry’s singular, authoritative ethos as Public Health regulator and reinforces her identification with the dominant communal “we” discussed in the first part of this analysis. It also implies that the rules themselves have been generated by, or at least belong to, this communal “we,” rather than being imposed by an external authority.

5 Concluding discussion

Although at first glance the pronoun “we” may seem like a small and therefore inconsequential feature of Henry’s public health communication, our analysis shows that it plays a significant role in constituting her ethos and constructing strong but shifting and ambiguous relationships with her implied public audience. While the particularities of our case study cannot be simply generalized to other contexts, our findings nonetheless both confirm previous research on the persuasive power of “we” to foster a sense of communal identity between expert and lay audiences (eg Carlo, Luzon, Tian, Tu, Beason, Varpio) and also show that, conversely, it can function to delineate hierarchically the exclusive identity of experts or health officials as distinct from the non-expert audiences they aim to address. The referential fluidity of “we” allows it to contribute in multi-faceted, complex ways to the rhetorical construction of ethos and to activating both symmetrical and asymmetrical “relationships among different social positions” [Condit, 2019, p. 177]. In our view, this rhetorical complexity indexes the hybrid set of identities and exigencies that inform the communication practices of public health officials during times of crisis.

Most notably, we see how use of inclusive “we” can cultivate a pro-social, communal sense of solidarity as a motivational basis for acting “together” to protect the health of all community members. We think that inclusive “we” contributes to Henry’s eunoia by signalling empathetic affiliation between herself and the audience as well arête by communicating a strongly communitarian ethic that she both presumes and asks the audience to share. Notably, the call to collective action that pervades Henry’s updates characterizes inclusive “we” not only as capable of performing the necessary actions, but also as situationally and morally obligated to do so, thus conferring both behavioural and ethical responsibility on British Columbian citizens.

Paradoxically, while this framework draws on the identity of an altruistic, communal “we” as the motivation for citizen action, the required behaviours are individual. “Doing our part” does not really mean “we” together doing one thing; it means, more precisely, each one of “us” acting, at an individual level, according to public health guidelines. In this sense, the communal ethos that inclusive “we” helps to generate obscures the essentially individualistic nature of the required behaviours. Additionally, Henry’s repeated exhortations that “we are all in this together” and “we need to work together” also implicitly constitute the citizens who make up this communal “we” as all equally responsible for and capable of acting according to public health guidelines. As critics have noted, this framing of the situation deflects attention from the significant socio-structural differences in citizens’ pandemic experiences and inequities in their capacities to effectively implement public health guidelines [Bowleg, 2020; Sobande, 2020; Speed, Carter & Green, 2022]. By eliding these important differences, inclusive “we” in Henry’s discourse, and likely the discourse of other public health officials, risks inscribing an exclusionary form of pandemic privilege.

The less dominant but nonetheless substantive uses of exclusive “we” throughout the public updates likewise indicate this pronoun’s diverse inflections in rhetorically shaping Henry’s relationship with British Columbian citizens. By contrast with the sense of proximity between speaker and audience signalled by inclusive “we,” exclusive “we” functions to distinguish Henry and her Public Health team from the audience in terms of expertise, healthcare provision, and — most strongly — regulatory authority. Although these uses foreground an asymmetrical relationship between speaker and audience, they nonetheless can be seen as contributing to phronesis, by demonstrating the expertise that “we” possess and share with the audience, and to arête, by emphasizing the diligent, careful, and responsive work that “we” as healthcare providers perform for citizens. The hierarchical distance between speaker and audience manifests most evidently in the use of “we” to designate Henry in her capacity as the province’s Public Health regulator. Here, the singular “we” contributes to Henry’s ethos by signalling this high status, while also mitigating the imposition of the orders she issues and diffusing responsibility for those orders.

While inclusive and exclusive uses of “we” are typically fairly easy to determine in Henry’s discourse, the boundaries between the two are also quite frequently blurred. Whether intentional or unintentional [Harwood, 2005], this blurring ambiguates who exactly “we” are, and therefore who knows what and who is responsible for what. The conflation of exclusive and inclusive “we” strengthens Henry’s relational ethos by implying shared knowledge, values, and responsibility in a way that dissolves boundaries between experts and non-experts, between public officials and citizens, and between governing bodies and those they govern. However, we would argue that these ambiguously exclusive/inclusive uses foster the impression of a symmetrical, dialogic relationship between Public Health and citizens that obscures its inherent power asymmetry. These uses also disperse responsibility for knowledge, action, and regulations into the broader communal “we.”

As a whole, our analysis shows that the pronoun “we” can contribute in vital and varying ways to the rhetorical construction of relational ethos as a “bridge” between public health officials and their implied citizen audiences [Condit, 2019]. At the same time, our study suggests that the role of “we” in building relations of social trust among citizens, experts, and institutions [Bucchi, 2021] may also be ambivalent and problematic. An important limitation of our analysis is that it only illuminates the kinds of audience identities and relationships that are evoked by Henry’s own discourse; an audience reception study of how British Columbians responded to this discourse (e.g., on social media) would therefore complement our study in valuable ways. Further research in other public health and science communication contexts internationally could likewise enrich and complicate the field’s understanding of the role pronouns play in constructing ethos and expert-citizen relationships.

Overall, we think that our study indicates the value for the fields of science and health communication of investigating how trust and relational ethos may be fostered through the rhetorical practice of pronoun usage by experts and public authorities. Importantly, our study nuances the dominant view that “we” functions primarily (if not entirely) to encourage affiliative identification between speaker and audience, by illustrating how it can also inscribe asymmetrical forms of rhetorical distance as well as how apparently inclusive forms of “we” may problematically and possibly unethically obscure this distance in some situations. For science and health communicators, our study suggests that “we” should be used judiciously, with careful attention to the distinction between inclusive and exclusive meanings and the different kinds of relationships between experts and citizens that these meanings imply.

References

-

Aristotle (2004). Rhetoric (W. R. Roberts, Trans.). Mineola, NY, U.S.A.: Dover Publications.

-

Beason, L. (1991). Strategies for Establishing an Effective Persona: an Analysis of Appeals to Ethos in Business Speeches. Journal of Business Communication 28(4), 326–346. doi:10.1177/002194369102800403

-

Besley, J. C., Lee, N. M. & Pressgrove, G. (2020). Reassessing the Variables Used to Measure Public Perceptions of Scientists. Science Communication 43(1), 3–32. doi:10.1177/1075547020949547

-

Bowleg, L. (2020). We’re Not All in This Together: On COVID-19, Intersectionality, and Structural Inequality. American Journal of Public Health 110(7), 917–917. doi:10.2105/ajph.2020.305766

-

Bucchi, M. (2021). To boost vaccination rates, invest in trust. Nature Italy. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/d43978-021-00004-y

-

Bucholtz, M. & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies 7(4-5), 585–614. doi:10.1177/1461445605054407

-

Charland, M. (1987). Constitutive rhetoric: The case of the peuple québécois. Quarterly Journal of Speech 73 (2), 133–150.

-

Condit, C. M. (2019). Public health experts, expertise, and Ebola: A relational theory of ethos. Rhetoric and Public Affairs 22 (2), 177–216. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.14321/rhetpublaffa.22.2.0177

-

De Cock, B. (2016). Reger, genre and referential ambiguity of personal pronouns. Pragmatics 26 (3), 361–378.

-

Dohle, S., Wingen, T. & Schreiber, M. (2020). Acceptance and adoption of protective measures during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of trust in politics and trust in science. Social Psychological Bulletin 15(4). doi:10.32872/spb.4315

-

Downing, L. H. & Perucha, B. N. (2013). Modality and personal pronouns as indexical markers of stance: Intersubjective positioning and construction of public identity in media interviews. In English Modality (pp. 379–410). doi:10.1515/9783110286328.379

-

Du Bois, I. (2012). Grammatical, Pragmatic and Sociolinguistic Aspects of the First Person Plural Pronoun. In N. Baumgarten, I. Du Bois & J. House (Eds.), Subjectivity in Language and Discourse (pp. 319–338). doi:10.1163/9789004261921_015

-

Giltrow, J. (2005). Modern Conscience: Modalities of Obligation in Research Genres. Text - Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 25(2). doi:10.1515/text.2005.25.2.171

-

Harwood, N. (2005). ‘We Do Not Seem to Have a Theory … The Theory I Present Here Attempts to Fill This Gap’: Inclusive and Exclusive Pronouns in Academic Writing. Applied Linguistics 26(3), 343–375. doi:10.1093/applin/ami012

-

Henry, B. (2020, November 13). The future of science communication in society [Panel participant]. In Symposium — Science communication 2020: tools and approaches for an era of uncertainty. Canadian Science Centre Policy Conference (virtual).

-

Henry, H. & Henry, L. (2021). Be kind, be calm, be safe. Canada: Allen Lane.

-

Hinks, A. (2020). White Rock band releases tribute tune for Dr. Bonnie Henry. Peace Arch News. Retrieved from https://www.peacearchnews.com/entertainment/white-rock-band-releases-tribute-tune-for-dr-bonnie-henry/

-

Hunt, K. P., Wald, D. M., Dahlstrom, M. & Qu, S. (2018). Exploring the Role of Trust and Credibility in Science Communication: Insights from the Sixth Summer Symposium on Science Communication. In K. Hunt (Ed.), Understanding the role of trust and credibility in science communication. Iowa State Summer Symposium on Science Communication. doi:10.31274/sciencecommunication-181114-6

-

Khosravi, M. (2020). Perceived Risk of COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Public Worry and Trust. Electronic Journal of General Medicine 17(4), em203. doi:10.29333/ejgm/7856

-

Leger (2021, May 26). COVID-19 and trust: A Postmedia-Leger poll. Retrieved from https://leger360.com/surveys/covid-19-and-trust-a-postmedia-leger-poll/

-

Little, T. (2020). Why is Dr. Bonnie Henry so effective communicating in this crisis? Coast Communications. Retrieved from https://www.coastcomms.ca/blogs/updates/why-is-dr-bonnie-henry-so-effective-communicating-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

-

Luzón, M. J. (2013). Public Communication of Science in Blogs. Written Communication 30(4), 428–457. doi:10.1177/0741088313493610

-

Makmillen, S. & Riedlinger, M. (2021). Markers of identification in Indigenous academic writing: A case study of genre innovation. Text & Talk 41(2), 165–185. doi:10.1515/text-2020-2073

-

Marsh, C. (2020). In an age of COVID villains, an unlikely hero has emerged: B.C.’s Dr. Bonnie Henry. National Post. Retrieved from https://nationalpost.com/news/in-an-age-of-covid-villains-an-unlikely-hero-has-emerged-b-c-s-dr-bonnie-henry

-

Mihelj, S., Kondor, K. & Štětka, V. (2022). Establishing Trust in Experts During a Crisis: Expert Trustworthiness and Media Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Science Communication 44(3), 292–319. doi:10.1177/10755470221100558

-

Miller, C. R. (2003). The Presumptions of Expertise: The Role of Ethos in Risk Analysis. Configurations 11(2), 163–202. doi:10.1353/con.2004.0022

-

Ofori, D. M. (2019). Grounding Twenty-first-Century Public Relations Praxis in Aristotelian ethos. Journal of Public Relations Research 31(1–2), 50–69. doi:10.1080/1062726x.2019.1634074

-

Palmer, F. R. (2001). Mood and modality (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Picard, A. (2020). Bonnie Henry is a calming voice in a sea of coronavirus. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-bonnie-henry-is-a-calming-voice-in-a-sea-of-coronavirus-madness

-

Porter, C. (2020). The top doctor who aced the coronavirus test. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/05/world/canada/bonnie-henry-britishcolumbia-coronavirus.html

-

Proctor, K. & Su, L. I.-W. (2011). The 1st person plural in political discourse — American politicians in interviews and in a debate. Journal of Pragmatics 43(13), 3251–3266. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2011.06.010

-

Rees, C. & Monrouxe, L. (2009). ‘Is it alright if I-um-we unbutton your pyjama top now?’ Pronominal use in bedside teaching encounters. Communication and Medicine 5(2), 171–182. doi:10.1558/cam.v5i2.171

-

Reynolds, B. & Quinn, S. C. (2008). Effective Communication During an Influenza Pandemic: The Value of Using a Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication Framework. Health Promotion Practice 9(4 suppl), 13S–17S. doi:10.1177/1524839908325267

-

Scheibman, J. (2014). Constructing Collectivity: ‘We’ Across Languages and Contexts. In T.-S. Pavlidou (Ed.), (pp. 23–44). doi:10.1075/pbns.239.05sch

-

Scotto di Carlo, G. (2014). The role of proximity in online popularizations: The case of TED talks. Discourse Studies 16(5), 591–606. doi:10.1177/1461445614538565

-

Siegrist, M. (2019). Trust and Risk Perception: A Critical Review of the Literature. Risk Analysis 41(3), 480–490. doi:10.1111/risa.13325

-

Siegrist, M. & Cvetkovich, G. (2000). Perception of Hazards: The Role of Social Trust and Knowledge. Risk Analysis 20(5), 713–720. doi:10.1111/0272-4332.205064

-

Siegrist, M. & Zingg, A. (2014). The Role of Public Trust During Pandemics. European Psychologist 19(1), 23–32. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000169

-

Smith, C. R. (2004). Ethos dwells persuasively: A hermeneutic reading of Aristotle on credibility. In M. J. Hyde (Ed.), The ethos of rhetoric (pp. 1–19). Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

-

Smith, C. R. (2020). Dr. Bonnie Henry has become B.C.’s Great Communicator. The Georgia Straight. Retrieved from https://www.straight.com/covid-19-pandemic/henry-is-bcs-great-communicator

-

Sobande, F. (2020). ‘We’re all in this together’: Commodified notions of connection, care and community in brand responses to COVID-19. European Journal of Cultural Studies 23(6), 1033–1037. doi:10.1177/1367549420932294

-

Speed, E., Carter, S. & Green, J. (2022). Pandemics, infection control and social justice: challenges for policy evaluation. Critical Public Health 32(1), 44–47. doi:10.1080/09581596.2022.2029195

-

Spoel, P., Lacelle, N. & Millar, A. (2021). Constituting good health citizenship through British Columbia’s COVID-19 public updates. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 136345932110641. doi:10.1177/13634593211064115

-

Tian, X., Kim, Y. & Solomon, D. H. (2021). The Effects of Type of Pronouns and Hope Appeals in Supportive Messages About COVID-19. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 40(5-6), 589–601. doi:10.1177/0261927x211044721

-

Tu, K. C., Chen, S. S. & Mesler, R. M. (2021). “We” are in This Pandemic, but “You” can get Through This: The Effects of Pronouns on Likelihood to Stay-at-Home During COVID-19. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 40(5-6), 574–588. doi:10.1177/0261927x211044799

-

Tworek, H., Beacock, I. & Ojo, E. (2020). Democratic health communications during Covid-19. Vancouver, Canada: UBC Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions.

-

Varpio, L. (2018). Using rhetorical appeals to credibility, logic, and emotions to increase your persuasiveness. Perspectives on Medical Education 7(3), 207–210. doi:10.1007/s40037-018-0420-2

-

Waddell, C. (2020). Carleton researchers find Canadians most trust public health officials on COVID-19. Carleton Newsroom. Retrieved from https://newsroom.carleton.ca/2020/carleton-researchers-find-canadians-most-trust-public-health-officials-on-covid-19/

-

Wainman, S. (2020). Local musician writes ‘The Ballad of Bonnie Henry’ in tribute to B.C.’s top doctor. Victoria Buzz. Retrieved from https://www.victoriabuzz.com/2020/04/local-jazz-musician-writes-the-ballad-of-bonnie-henry-in-tribute-to-b-c-s-top-doctor

Authors

Philippa Spoel is a Professor in the School of Liberal Arts, Master of Science

Communication, and PhD in Interdisciplinary Health at Laurentian University, Canada.

Her research focuses on rhetorical criticism of public health, science, and environmental

communication.

E-mail: pspoel@laurentian.ca

Alexandra Millar is a graduate of the Master of Science Communication Program at

Laurentian University, Canada. Committed to multidisciplinary research aimed at better

communicating social and environmental justice, she is currently conducting research at

Queen’s University, Canada that synthesizes best practices and frameworks for the

development of inclusive and anti-racist science communication training.

E-mail: alexzmillar@gmail.com

Naomi Lacelle is a language arts teacher with degrees in English Literature and in

Education from Laurentian University, Canada. Her interest in rhetorical analysis and

effective communication informs her educational practice and creation of analytical

written content for curriculum development.

E-mail: naomijean1998@hotmail.com

Aarani Mathialagan is a science communicator for the Government of Canada. She

holds a Master of Science Communication degree from Laurentian University, Canada.

Her current work focuses on improving transparency and bridging the gap between

expert and non-expert audiences.

E-mail: aamathialagan@gmail.com

Endnotes

1BC has five Regional Health Authorities which deliver health services within their respective geographic regions.

2Pro-social messaging asks individuals to act for the good of others or the community [Tworek et al., 2020, p. 105]. Neo-communitarianism combines a neoliberal ideology of self-responsibilization with a communitarian ideal of active citizenship and community values [Spoel et al., 2021].

3Within these excerpts, there are 2061 occurrences of “we” compared to 215 occurrences of “I” and 384 occurrences of “you.” Within 10 randomly selected updates from our corpus, “we” occurs on average 83 times per update compared to an average of 9 times for “I” and 20 for “you.”