1 Introduction

There are a wide range of methodological approaches that seek to involve academic researchers and non-academic stakeholders, end-users and/or members of the public to a greater or lesser degree in the co-production of research and/or research-related outputs in ways that are relevant and meaningful to them [e.g. Reed, in press ; Oreszczyn and Lane, 2017 ; Martin, Carter and Dent, 2017 ; Hoggart, 2017 ; Seale, 2016 ; Collins, 2015 ; Weller, 2014 ; Guston, 2013 ; Molyneux and Bull, 2013 ; Hartnett, Daniel and Holti, 2012 ; Owen, Macnaghten and Stilgoe, 2012 ; Burnard et al., 2006 ]. In essence, I argue that these are all examples of engaged research, but conceptualised from particular disciplinary backgrounds.

“Engaged research encompasses the different ways that researchers meaningfully interact with various stakeholders* over any or all stages of a research process, from issue formulation, the production or co-creation of new knowledge, to knowledge evaluation and dissemination”.

* Stakeholders may include user communities, and members of the public or groups who come into existence or develop an identity in relationship to the research process.

[Holliman et al., 2015 , p. 3]

This definition was developed as part of an institutional project designed to change the academic practices of researchers with the aim of improving the overall quality of engagement activities at the Open University (OU), UK. The definition offers a principled response to confusion amongst researchers about how ‘public engagement’ is defined in different disciplines [Grand et al., 2015 ]. I led a small, multi-disciplinary team as we worked in consultation with researchers from across the university to develop this institutionally-approved definition [Holliman et al., 2015 ]. Our aim was to create a shared understanding of engaged research as a way of fostering clear and consistent communication. Ultimately, the development of a cross-disciplinary understanding of this concept allowed us to address questions of professionalisation, e.g. by using the definition to underpin criteria for assessing quality in relation to academic practices of engaged researchers [Holliman et al., 2015 , pp. 16–19].

2 UK initiatives to engender organisational and cultural change

The work to embed the principles and practices of engaged research at the OU is part of a wider programme of organisational change across the UK higher education sector. UK academics are required to plan for, and evidence, social and/or economic impacts arising from their research, and their institutions need to put in place strategies, training, support mechanisms and the infrastructure to support them [RCUK, 2010 ].

To this end, the OU has benefited from, and contributed to, publicly-funded programmes of culture change. For example, from 2012–2015, the OU was funded by Research Councils UK (RCUK) as one of eight national Public Engagement with Research (PER) Catalysts [Duncan and Manners, 2016 ]. Based in research-intensive universities, the PER Catalysts drew on the learning from the Beacons for Public Engagement [NCCPE, 2012 ] to change their respective organisational cultures by embedding public engagement within strategic planning for research and the operational practices of researchers.

The OU’s project, ‘An Open Research University’ [Holliman et al., 2015 , p. 1], had two overarching aims:

- To work with researchers at all levels and across all academic domains to create the conditions where engaged research can flourish.

- To raise the profile of the OU’s international reputation for excellence in engaged research.

Our approach to organisational change was informed by action research, embedding evaluation throughout our PER Catalyst through iterative cycles of planning, action, analysis and reflection [Grand et al., 2016 ; Grand et al., 2015 ]. We worked collaboratively with researchers across the institution to identify and implement strategies that work for them and the stakeholders, user communities and members of the public who engage with OU research.

Given the likely scale and envisaged complexity of organisational change within the OU we set out to produce an evidence base through interviews with research leaders and surveys gathered from researchers at all grades. The resulting evidence base informed interventions that improved our systems, governance and processes. We then studied the outcomes to direct further research questions [Grand et al., 2016 ; Grand et al., 2015 ]. I argue that this evidence-based, ‘engaged research’ approach was central to the success of our PER Catalyst work, and therefore to the professionalisation of academic practices within the institution.

3 Assessing purpose, process and practice to inform change

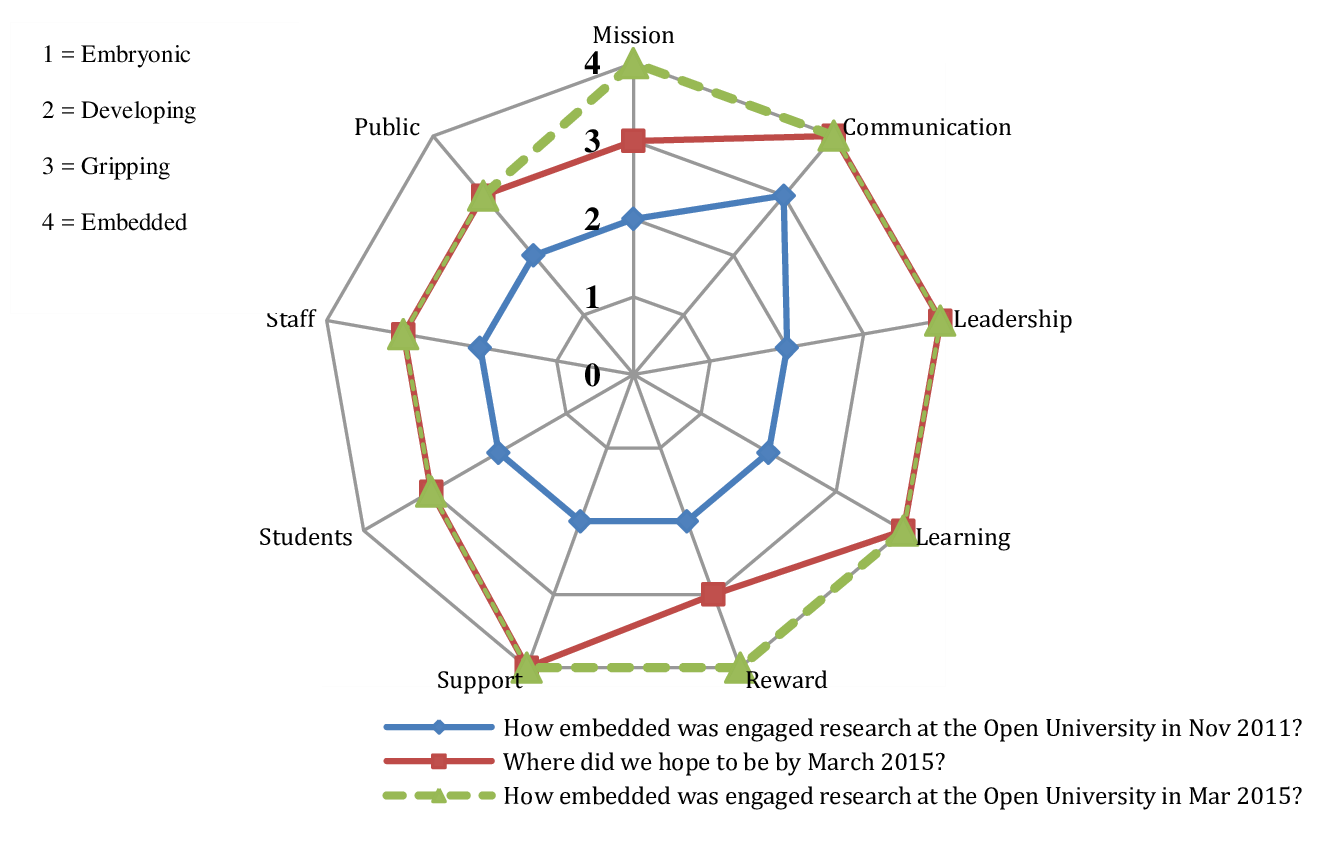

Our PER Catalyst project gathered evidence from research leaders by using the ‘EDGE Tool’ [NCCPE, 2010 ] to make an initial assessment of our support for engaged research. This tool is organised under three themes, each of which includes three sub-categories: purpose (leadership, mission, communication); process (learning, support, recognition); and practice (staff, students, publics). Together, the themes and categories provide a framework for analysis, reflection, planning and implementation.

We applied the nine categories outlined by the EDGE Tool to assess the university’s position in November 2011 (Figure 1 ; in blue), comparing this with where we planned to be by March 2015 at the end of the project (Figure 1 ; in red) [Holliman et al., 2015 , pp. 7–8].

The initial assessment made in November 2011 highlighted the need for the institution to change, and provided a framework to organise how this could be achieved. As such, each of the nine elements in the EDGE Tool related to a PER Catalyst project objective and a related work package.

Our overarching aim was to transform The Open University’s research culture from a ‘developing’ phase, following the assessment in November 2011, to a ‘gripping’ or ‘embedding’ phase by March 2015. We made progress in all nine of the work packages; in two of them we went beyond our planned targets (Figure 1 , in green) [Holliman et al., 2015 , pp. 7–8].

We developed and implemented a successful strategy for engaged research that extended our commitment beyond open learning, laying the foundations to change the culture of our research, and aligning this with our mission to be ‘open to people, places, methods and ideas’.

The legacy of our work to professionalise the academic practices of engaged research is embedded in the OU’s institutional governance, not least following the introduction of a Knowledge Exchange Profile as an academic promotion route from Lecturer to Professor [Parr, 2015 ]. In effect, we have measures in place to reward excellence. My work since the end of the PER Catalyst has focused on the professionalisation of academic practices in relation to engaged research. What mechanisms can be used to create a culture of aspiration where engaged research is seen as an equivalent ‘third stream’ route to career progression alongside research and teaching [Whitchurch, 2013 ]?

4 Surveying academic practices

We collected a range of evidence through our PER Catalyst project to better understand the academic practices of OU researchers [e.g. Grand et al., 2016 ; Grand et al., 2015 ]. This included participation in two UK-wide surveys of research leaders and researchers, adding four institution-specific questions that addressed aspects of engaged research [Grand et al., 2015 ]. We repeated this work in 2015, but with a slightly different focus, exploring ideas about quality and recognition in relation to engaged research. I undertook this work again in 2017, working with Gareth Davies and the OU’s Academic Development Team to include two questions that explored OU researchers’ current thinking about engaged research. Of these, one of the questions asked researchers to consider how engaged research could be supported at the university:

“What mechanisms do you think the University could introduce to support researchers as they work with stakeholders, end-users and members of the public to generate and evidence social and/or economic impacts from research?”

The response rates to the Principal Investigators and Research Leaders Survey (n=177; 23%) and Careers in Research Online Survey (n=37; 36%) in 2017 were very slightly higher in percentage terms (+1%) than the surveys completed at the university in 2015 and 2013. The responses from OU researchers can be categorised into a number of different themes. Here I include a descriptive sample of the responses that focus on the need to address questions of Support, as defined by the NCCPE’s (2010) EDGE Tool.

“Train heads of school to understand that research is not only focussed at the OU and internally but it has national and international impact.” (Principal Investigator)

“Promote this aspect of research by valuing it more and allowing more time allocation within workload planning.” (Principal Investigator)

“…time would be really useful here. Our project already engages with stakeholders and end-users, but time to really share findings and resources that could make a difference in practice would be really valuable (more than just a one-off event) — sustained engagement is crucial here.” (Researcher)

“Include this in appraisal process and built-in-time [sic] in everyday workload for this to happen.” (Principal Investigator)

“Be more equitable and value every individual researcher. There is a great deal of ‘hidden’ research which adds value because some academics do not have the confidence in the systems, to put themselves forward.” (Principal Investigator)

This selection of quotes from OU researchers complements the findings from recent (and previous) reports [Owen, Featherstone and Leslie, 2016 ], research [Jensen and Holliman, 2016 ], and surveys [TNS BMRB, 2015 ]. They also correspond with the requirements of the UK’s Concordat for Engaging the Public with Research , Principle 3 [RCUK, 2010 ], in particular the need for effective support procedures to be in place from recruitment through all aspects of a researcher’s work.

Whilst the OU’s PER Catalyst team can claim to have put in place mechanisms for recognition, e.g. through the new promotion profiles, it is clear that the support mechanisms that underpin resource allocation and the professionalisation of academic practices require further attention. It follows that we (and many other universities) have some way to go before we have an aspirational culture of reflective practice in place, where excellent researchers are confident that by adopting the principles and practices of engaged research they have genuine potential to enhance their career.

5 Engaged Research as a route to epistemic justice

This paper contributes to a collection of commentaries on the question of professionlisation in science communication. This focus raises questions about the purposes for organisational and cultural change in relation to engaged research. These can be categorised as:

- Normative, e.g., Who should have a voice in research?

- Substantive, e.g., What types of expertise and/or experience are likely to improve the research and/or the social and/or economic impacts derived from it?)

- Instrumental, e.g., Will this improve my career prospects, and what are funders likely to support?

Through our work at the OU to embed culture change in academic practices, we have linked these purposes, arguing that, if done well and over time , engaged practices can enhance the quality of research, improve the social and economic significance of the resulting impacts for all participants, and generate evidence of sustained excellence in academic practice [e.g. Holliman and Warren, 2017 ; Scanlon, 2017 ].

Here I emphasise, like others working in similar contexts [Medvecky and Leach, 2017 ], that the necessity to improve the quality of engaged research through superior academic practices should have a moral imperative. It follows that success in embedding engagement within academic practices would be measured by a reduction in epistemic injustice [Fricker, 2007 ] and the promotion of ‘fairness in knowing’ [Medvecky, 2017 ]. A key driver for this change is effective upstream planning for engaged research, matched by clear rules of engagement and fairness in their application [Holliman et al., 2017 ].

Approaching engaged research in this way addresses the two forms of epistemic injustice that Fricker [ 2007 ] identifies: testimonial and hermeneutical. As with normative configurations of engaged research, testimonial injustice raises questions about who should have a voice in research, but also how voices in research are heard in wider society [Medvecky, 2017 ]. This raises important questions about the creation of ‘publics’ for engaged research include, ‘Who could/should have a voice in research?’, ‘Who is excluded, why, and is this justified?’ Colleagues at the Open University proposed a solution to this challenge by calling for researchers to work ‘upstream’ to improve their preparedness to co-create ‘publics’ for research [Mahony, 2015 ]. Further, if as researchers we engage with publics through research, we should ensure that those who have participated (researchers and publics) are heard when the research findings and other outputs are shared. This could take the form of co-authored publications [e.g. Holliman et al., 2017 ], forms of communication that represent partnership working [e.g. NCCPE, 2017 ], acknowledgements [e.g. Holliman et al., 2009b ], and/or other forms of attribution [e.g. Collins et al., 2015 ].

In describing hermeneutical injustice, Fricker [ 2007 ] describes an absence of knowing that an injustice has occurred, allied with a lack of opportunities and the skills necessary to participate. I argue that this applies to engaged research in two ways: 1) whether researchers have a shared understanding of the principles and practices of engaged research; and 2) whether participating ‘publics’ have sufficient conceptual grounding in engagement to be able to contribute in ways that are meaningful to them and to the research in question. Much of our work has focused on the former (changing academic practices), with a view to improving the ways that researchers engage with ‘publics’.

Improving levels of hermeneutical justice through engaged research places a responsibility on researchers and research managers to explore why they (and their ‘publics’) are engaging, how, when (and how often), where and to what ends. Care and attention need to be taken in how engaged research should take place to ensure that the mechanisms are fair, equitable and appropriate. These decisions should ideally be made upstream, although I acknowledge, like others, that in some instances they will need to be revisited at appropriate points in the research cycle [Reed, in press ; Holliman et al., 2017 ].

Professional development clearly has a role in opening up the possibilities for researchers to engage with relevant publics in meaningful ways, and to ensure that participants are suitably recognised for their contributions [Holliman and Warren, 2017 ; Miller, Fahy and the ESConet Team, 2009 ]. However, influencing support mechanisms, in combination with training and recognition, is essential for changes in academic practices are sustainable. Support for engaged research should start during undergraduate and postgraduate education and training [Holliman et al., 2009a ]. It should be addressed through recruitment criteria through induction, training and mentoring, continuing through prioritisation of resources through workload planning and routine monitoring of performance. Significantly, support for engaged research must address questions of leadership [Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (LFHE), 2017 ], to include questions of succession planning. Who are the engaged research leaders for the next generation? In short, for engaged research to become fully embedded requires a systematic and ongoing examination of all areas of academic practice.

Through training, support and recognition we can encourage virtuous behaviour in the planning, enactment, and evaluation of engaged research, offering ‘publics’ authentic opportunities to meaningfully interact over any or all stages of a research process, from issue formulation, to the production or co-creation of new knowledge, to knowledge evaluation and dissemination. If researchers become more professional, improving rigour in process through a principled approach that can be applied across academic domains and beyond, all parties to these processes will benefit from better quality engagement [Holliman, 2017 ].

Acknowledgments

The research discussed in this paper was supported through the following awards: RCUK Public Engagement with Research Catalyst (EP/J020087/1); RCUK School University Partnership Initiative (EP/K027786/1); and a NERC Innovation Award (NE/L002493/1). Jane Perrone and Brian Trench provided helpful comments on a draft of this paper.

References

-

Burnard, P., Craft, A., Cremin, T., Duffy, B., Hanson, R., Keene, J., Haynes, L. and Burns, D. (2006). ‘Documenting ‘possibility thinking’: a journey of collaborative enquiry’. International Journal of Early Years Education 14 (3), pp. 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760600880001 .

-

Collins, T., Devine, P., Holliman, R., Turner, L., Roberts, D., Stratford, T., Banks, E., Griffiths, C., Ojo, O. and Russell, M. (2015). Communicating partnership: Participatory design with young people. School-University Partnerships Initiative Case Study. Bristol, U.K.: NCCPE. URL: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/case-studies/communicating-partnership-participatory-design-with-young-people .

-

Collins, T. (2015). ‘Enhancing Outdoor Learning Through Participatory Design and Development: A Case Study of Embedding Mobile Learning at a Field Study Centre’. International Journal of Mobile Human Computer Interaction 7 (1), pp. 42–58. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijmhci.2015010103 .

-

Duncan, S. and Manners, P. (2016). Culture change — embedding a culture of public engagement. Bristol, U.K.: NCCPE. URL: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/nccpe_catalyst_report_may_2016.pdf .

-

Duncan, S. and Oliver, S. (2017). ‘Editorial: Motivations for engagement’. Research for All 1 (2), pp. 229–233. https://doi.org/10.18546/rfa.01.2.01 .

-

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

-

Grand, A., Davies, G., Holliman, R. and Adams, A. (2015). ‘Mapping public engagement with research in a UK University’. PLOS ONE 10 (4), e0121874, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121874 . PMID: 25837803 .

-

Grand, A., Holliman, R., Collins, T. and Adams, A. (2016). ‘“We muddle our way through”: shared and distributed expertise in digital engagement with research’. 15 (4), A05. URL: http://jcom.sissa.it/archive/15/04/JCOM_1504_2016_A05 .

-

Guston, D. H. (2013). ‘Understanding ‘anticipatory governance’’. Social Studies of Science 44 (2), pp. 218–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312713508669 .

-

Hartnett, E. J., Daniel, E. M. and Holti, R. (2012). ‘Client and consultant engagement in public sector IS projects’. International Journal of Information Management 32 (4), pp. 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.05.005 .

-

Hoggart, L. (2017). ‘Collaboration or collusion? Involving research users in applied social research’. Women’s Studies International Forum 61, pp. 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2016.08.005 .

-

Holliman, R. (23rd February 2017). Assessing excellence in research impact. National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement Blog. Bristol, U.K.: NCCPE. URL: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/blog/assessing-excellence-research-impact .

-

Holliman, R. and Warren, C. J. (2017). ‘Supporting future scholars of engaged research’. Research for All 1 (1), pp. 168–184. https://doi.org/10.18546/rfa.01.1.14 .

-

Holliman, R., Whitelegg, E., Scanlon, E., Smidt, S. and Thomas, J., eds. (2009a). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Holliman, R., Adams, A., Blackman, T., Collins, T., Davies, G., Dibb, S., Grand, A., Holti, R., McKerlie, F., Mahony, N. and Wissenburg, A. (2015). An open research university: final report. Milton Keynes, U.K.: The Open University. URL: http://oro.open.ac.uk/44255/ .

-

Holliman, R., Collins, T., Jensen, E. and Taylor, P. (2009b). ISOTOPE: Informing Science Outreach and Public Engagement. Final Report of the NESTA-funded ISOTOPE Project. Milton Keynes, U.K.: The Open University. URL: http://oro.open.ac.uk/20090 .

-

Holliman, R., Davies, G., Pearson, V., Collins, T., Sheridan, S., Brown, H., Hallam, J. and Russell, M. (2017). ‘Planning for engaged research: a collaborative ‘Labcast’’. In: The Digitally Agile Researcher. Ed. by N. Kucirkova and O. Oliver Quinlan. Maidenhead, U.K.: Open University Press, pp. 88–106. URL: http://oro.open.ac.uk/50411 .

-

Jensen, E. and Holliman, R. (2016). ‘Norms and Values in UK Science Engagement Practice’. International Journal of Science Education, Part B 6 (1), pp. 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2014.995743 .

-

Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (LFHE) (2017). Research Leaders’ Impact Toolkit. London, U.K.: LFHE. URL: https://www.lfhe.ac.uk/en/research-resources/publications-hub/research-leaders-impact-toolkit-publications.cfm .

-

Mahony, N. (2015). Designing Public-Centric Forms of Public Engagement with Research. Milton Keynes, U.K.: The Open University. URL: http://oro.open.ac.uk/42551 .

-

Martin, G. P., Carter, P. and Dent, M. (2017). ‘Major health service transformation and the public voice: conflict, challenge or complicity?’ Journal of Health Services Research & Policy , p. 135581961772853. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819617728530 .

-

Medvecky, F. (2017). ‘Fairness in Knowing: Science Communication and Epistemic Justice’. Science and Engineering Ethics . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9977-0 .

-

Medvecky, F. and Leach, J. (2017). ‘The ethics of science communication’. JCOM 16 (4), E. URL: https://jcom.sissa.it/archive/16/04/JCOM_1604_2017_E .

-

Miller, S., Fahy, D. and the ESConet Team (2009). ‘Can Science Communication Workshops Train Scientists for Reflexive Public Engagement?’ Science Communication 31 (1), pp. 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547009339048 .

-

Molyneux, S. and Bull, S. (2013). ‘Consent and Community Engagement in Diverse Research Contexts: Reviewing and Developing Research and Practice’. Participants in the Community Engagement and Consent Workshop, Kilifi, Kenya, March 2011. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 8 (4), pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2013.8.4.1 .

-

National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE) (2010). Self-assess your institution . URL: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/work-with-us/completed-projects/beacons .

-

— (2012). The Beacons for Public Engagement . URL: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/work-with-us/completed-projects/beacons .

-

— (2017). School-University Partnerships: Lessons from the RCUK-funded School-University Partnership Initiative. Bristol, U.K.: NCCPE. URL: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/nccpe_supi_lessons.pdf .

-

Oreszczyn, S. and Lane, A., eds. (2017). Mapping environmental sustainability: Reflecting on systemic practices for participatory research. Bristol, U.K.: Policy Press. URL: http://oro.open.ac.uk/49474 .

-

Owen, D., Featherstone, H. and Leslie, K. (2016). The state of play: public engagement with research in UK universities . Prepared for RCUK and the Wellcome Trust. URL: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/sites/default/files/publication/state_of_play_final.pdf .

-

Owen, R., Macnaghten, P. and Stilgoe, J. (2012). ‘Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society’. Science and Public Policy 39 (6), pp. 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs093 .

-

Parr, C. (2nd April 2015). ‘Open University maps new routes to career progression’. Times Higher Education . URL: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/open-university-maps-new-routes-to-career-progression/2019410.article .

-

Reed, M. (in press). ‘Pathways to policy impact: A new approach for planning and evidencing research impact’. Evidence and Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice .

-

Research Councils UK (2010). Concordat for Engaging the Public with Research . URL: http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/pe/Concordat/ (visited on 17th March 2016).

-

Scanlon, E. (2017). ‘Concepts and Challenges in Digital Scholarship’. Frontiers in Digital Humanities 4, pp. 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdigh.2017.00015 .

-

Seale, J. (2016). ‘How can we confidently judge the extent to which student voice in higher education has been genuinely amplified? A proposal for a new evaluation framework’. Research Papers in Education 31 (2), pp. 212–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2015.1027726 .

-

Stirling, A. (2008). ‘“Opening Up” and “Closing Down”: Power, Participation, and Pluralism in the Social Appraisal of Technology’. Science, Technology, & Human Values 33 (2), pp. 262–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243907311265 .

-

TNS BMRB (2015). Factors affecting public engagement by researchers: A study on behalf 1006 of a consortium of UK public research funders . URL: https://wellcome.ac.uk/news/what-are-barriers-uk-researchers-engaging-public .

-

Weller, M. (2014). The Battle For Open. London, U.K.: Ubiquity Press. https://doi.org/10.5334/bam .

-

Whitchurch, C. (2013). Reconstructing identities in higher education: The rise of third space professionals. Abingdon, Oxon, U.K.: Routledge.

Author

Richard Holliman is Professor of Engaged Research at The Open University, UK. Through his teaching and engaged research, he explores relationships between academic researchers and non-academic stakeholders. He is particularly interested in the cultural and organizational change in higher education, and how the practices of engagement shape and frame contemporary research. His publications are listed at: http://oro.open.ac.uk/view/person/rmh47.html . E-mail: Richard.Holliman@open.ac.uk .