1 Background

Based on the research project DFG-KOPRO-Int: concepts of “Co-production” and its influence on the development of inclusive urban spaces — an international comparative study on theories and practices , this paper aims to contribute to understandings of co-production processes in urban and housing developments. Co-production discourses in the built-environment disciplines have grown in the last decades to be an important driver for knowledge building especially in terms of implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For example, The New Urban Agenda (NUA) acknowledges that sustainable integrative urban development needs to be understood in a holistic way, with a focus on different local circumstances, actor constellations and their processes. Hence, co-production frameworks are worth being thought of as tools to reconsider traditional knowledge hierarchies and silos and can foster alternative comprehensions towards integration and inclusion in processes. In this article, we define learnings from co-productive urban development and housing projects to understand involved actors, their process structures and material quality of the projects.

DFG-KOPRO-Int by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft is built in the frame of an international study and referring into different forms of co-production practices mainly from Europa and Latin America. It investigates interdependencies, benefits and specific new instruments of collaborative structures currently being developed and tested in projects. The study also inquires into social-spatial processes and material qualities.

1.1 1. Learning from inhabitants’ local practices in the development of housing

The call to “learn from inhabitants’” local practices and synthesizing mechanisms to develop better solutions for housing and urbanism is as old as the study of Turner on user-led housing and urban informality [Turner, 1976 ]. These approaches, during the 1970s, were discontinued in architecture and urban practices and reasons for their perceived failure were never fully analysed. However, in recent years, research on local practices has experienced a new uptake across the global north and south. Architects have developed a new interest in providing housing solutions such as co-designing with different actors to fit local requirements. In this line, the concept of co-production , which is constituted in a mutual relationship between different actors, such as the state, private sector and civil society, is emerging in academic discourses and urban as well as local housing policies. It has been applied in the urban development field in various contexts, in particular, in governance and actor structure-network inquiries.

Our research demonstrates different fields of practices — to picture the most prominent ones — like incremental housing projects and neighbourhood actions that incorporate cooperative approaches to overcome social inequality [Aravena and Iacobelli, 2013 ] and the refurbishment of housing projects for the urban poor [Lacaton and Vassal, 2015 ]. Also, ephemeral spaces that can enhance test-fields for possible future developments work with co-production as principles for sharing economies (Prinzessinnengarten am Moritzplatz 2009). In Urban regeneration projects (Villa Frei 2014) or urban sustainability projects (Reallabore 2018) the reconfiguration of public space for common approaches goes frequently together with cooperative structures for its development.

Teams of planners, sociologists and ethnographers [Simone, 2004 ; Miraftab, 2009 ; McFarlane, 2011 ] are providing an understanding of the complex social dimensions and lessons to be learned from such practices. This leads to a new perception and appreciation of citizen practices beyond a unilateral-project approach.

1.2 2. Co-production and commoning

According to Elinor Ostrom [ 1996 ], co-production was developed in the late 1970s to reconfigure government-funding frameworks . Co-production thus comfortably fits in the performance of the “governance equation” identified by Harpham and Boateng [ 1997 ] where citizens are considered fundamental stakeholders to mobilise resources for service provision by setting up a new logic of development. Ostrom recognized the origin of the term in a direct relationship of individuals with urban policies, proving that the improvement in the production of service is difficult without the participation of those who are supposed to be beneficiaries.

Co-production implies that citizens can play an active role in the public generation of goods and services in which they are directly involved or that are of importance to them. In particular, development processes motivated by civil society, so-called user-centered processes, should provide decisive impulses for long-term development [Kuhn, 2016 ]. This is particularly well understandable in Ostroms framing of Commoning , that exists when following parameters are given: (a) the existence of a common or collective resource, (b) a community, and (c) the process that secures and reproduces that resource [Ostrom, 1996 ]. She explained her work while detailing cases in the global north and south in education, health, security and public infrastructure. These approaches synthesize the potentials that may exist in the relationship between the regular producer of service (often the state) and the actors, clients or recipients who aim for improvement and transformation by that provision, into safer or healthier environments [De Angelis, 2017 ; Blomley, 2016 ]. Urban development, including housing as a habitat, can be considered a service and a good and it remains important to understand both the actions initiated by the public power and the actions that communities carry out [Torrent, 2020 ].

Hence, Ostrom’s studies raise appreciation of environments that are built from teams of actors and spaces that are shaped according to the needs and experiences of their inhabitants. She therefore advocates a savoir-vivre approach rather than an abstract planning logic. Furthermore, Ostrom’s definition brought up the level of the Urban Commons noticeably in urban contexts.

1.3 3. Lessons from co-production in housing and urban projects

In our empirical research study we set the focus on co-productions’ assumed four key dimensions, while researching specific new instruments of cooperation that are currently being developed and tested in projects, and their impact on socio-spatial material consequences.

A. Actors. The achievement of a set of interdisciplinary actors and multiple stakeholders including the public, privates, civil society and communities.

In recent years, the engagement of multiple actors has increased in the creation of urban spaces in cities, in particular, from the state, private sector and civil society sphere. Despite their limited scope/scale of involvement and interest, scholars have perceived the patterns of multi-actor engagement as a positive influence on projects. One of the main stimuli for such a development is ‘the knowledge itself of citizens/inhabitants own living environment’. Involved citizens can generate and share knowledge, and qualify themselves through further accumulated experiences in such projects [Alfaro-d’Alençon and Bauerfeind, 2017 ]. Though, the return-oriented development projects consist of certain correlations between the scope of a project and private sector actors including the power asymmetries (ibid).

Municipalities learn at best from and within the practices of self-organised citizens in urban development projects in terms of preservation/re-use//regain developments and they can become development engines.

In the frame of our study on social-spatial inclusiveness, various forms of cooperative actor structures have been observed (the case of European context — Berlin city), who are able to take part in processes. For example, in the realm of urban conversion and renewal projects, a higher percentage of citizen involvement is identified in comparison to standard urban development projects [Alfaro-d’Alençon and Bauerfeind, 2017 ].

B. Processes. How a resource is mutually distributed, created and shaped by different logics, as theoretical and practical logics reflect on a process-based perception of the context.

Many current initiatives/campaigns promote collective practices dealing with the production and management of resources, surrounding processes such as the (re)production of material and immaterial common goods and spaces in general, rather than only with the resources themselves [Gruber and Ngo, 2018 ]. In the urban context, the notion of commoning reflects processes of negotiating differences/conflicts between the individual, the community and society beyond the influences of market and state and represents the search for an alternative/self-determined approach (ibid). For example, the ‘ Does effective planning really exist editorial project’ [Lepratti and Alfaro-d’Alençon, 2018 ] highlighted the responsibility of taking a clear position by urban planners/architects in such situated processes and negotiations. Since these initiatives/projects aim to challenge the prevailing social and political structures and search for new forms of collective, yet pluralistic, governance.

Considering the scholarly discourses of today‘s scarce common resources and decreased interdependency of communities/livelihoods, the concept of urban commons has been revived again in built environment discipline (e.g. by including urban spaces and processes around it) to produce sustainable urban ecosystems [Gidwani and Baviskar, 2011 ]. The scholar Michel Bauwens focuses on the understanding of the varied nature of the common-pool resources that pre-existed in urban territories. This understanding is explained in three categories of common-pool resources: inherited commons (such as land, water, forest), immaterial commons (cultural, local and craft knowledge) and material commons such as large man made reserves of materials [Gruber and Ngo, 2018 ].

In this scenario, urban governance models offer a platform to develop a new process of organizing and distributing (spatial) demands and common resources. The growing number and diversity of stakeholders require direct and open communication as well as the inclusion of various levels of knowledge [Alfaro-d’Alençon and Bauerfeind, 2017 , p. 10]. However, frequently local planning structures present short-term approaches or uncertainty for the new planning tasks due to their complexity, in particular, on clarifying the roles (ibid). Despite their temporary presence in urban practices, these self-initiated and non-conformist approaches can be identified as an important part of new alternative instruments around planning operations.

Scholarly research hence argues for transparency and accountability within the cooperation — this is crucial so that conflicts are overcome and pressure does not immediately endanger the entire collaboration [Coaffee and Healey, 2003 ]. In fact the amount of actors involved in the realisation of urban spaces has increased, and various forms of cooperative approaches in urban development between state, private sector, and civil society actors have been established in recent years. However, as can be seen as a general pattern from the research, planners have still little knowledge or fewer methods concerning cooperative planning practice with civil society as participatory budgeting or division of planning responsibility [Alfaro-d’Alençon and Bauerfeind, 2017 ].

C. Access. As to understand that access to knowledge and its exchange is the prerequisite for its production and enhancing arenas for inclusion.

The contribution of the civil actors contributes significantly to the change in the knowledge pool and the competency models in urban development projects [Brownill and Parker, 2010 ]. Different researches in the last years show that this knowledge is produced for individual situations and through a wide network of actors, and contributes to specific spatial and functional solutions for the neighbourhood development. This spatial practice breaks the understanding of planning as the only discipline influencing the living environment, and a shift can be observed in the importance of knowledge building. Therefore, unlocking the locally produced knowledge is gaining in importance, and is becoming a new challenge in project development. The focus is set on different local circumstances and urban situations, different actor constellations and co-benefits [Dellenbaugh et al., 2015 ]. The collective knowledge production between the state and civil society is identified as a relevant contribution to theory building in the planning sciences. This can imply multi-level governance settings and focus on the operationale level or on the strategic level [Nesti, 2018 ].

D. Spaces. A reflection on different operative fields such as urban areas, public spaces, housing issues, even public buildings, evidence fields of synergies and cross-fertilization between cultural agents and financial sources from different sectorial policies.

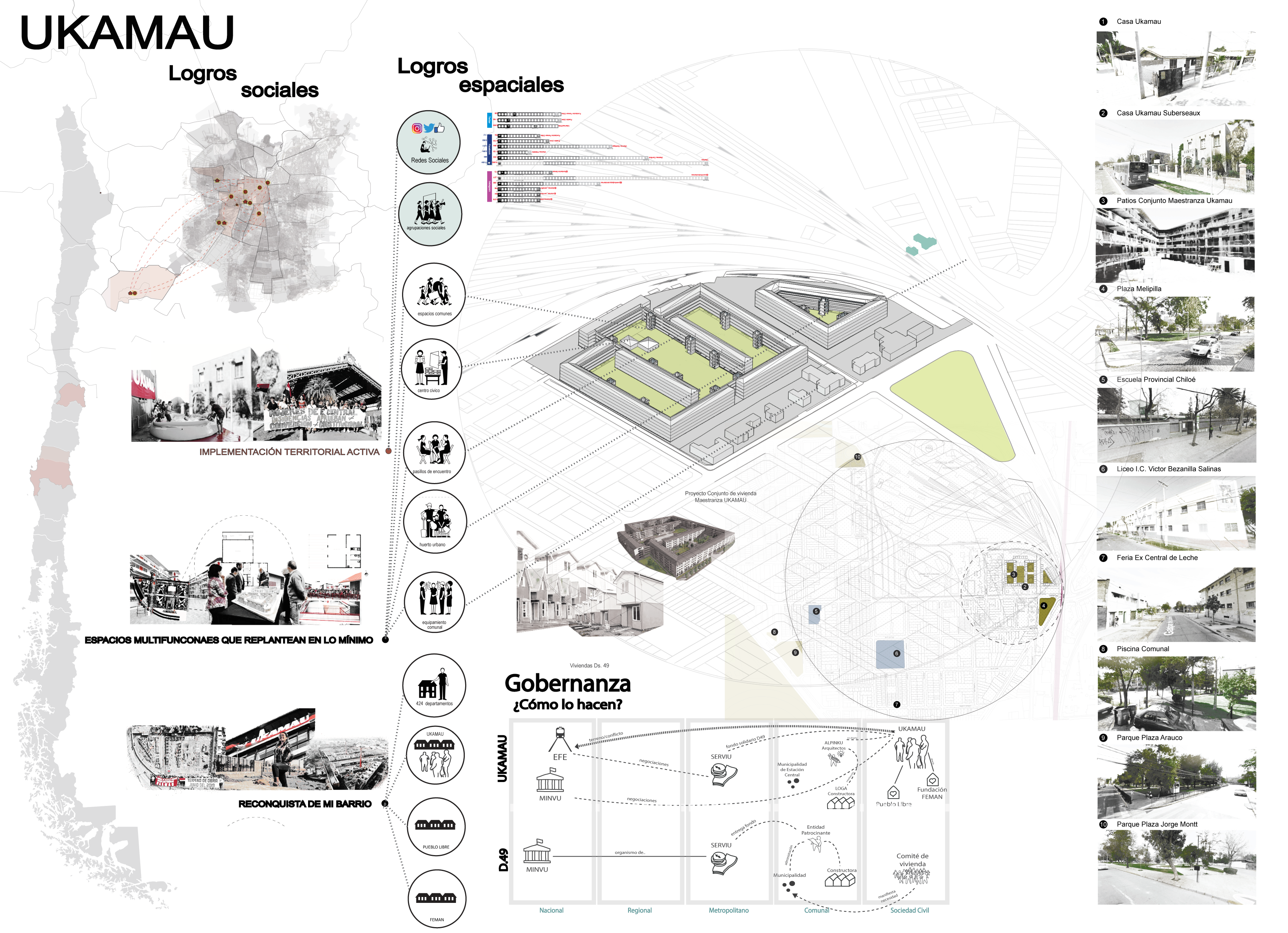

Strong citizen/civic involvement in the implementation of the project offers a promising approach for the conversion/maintenance of areas that had previously accommodated obsolete uses or (infrastructural) buildings and ensure interesting specific solutions and tailor based designs (Figure 1 ). From such practices it appears apparent that the (local) neighbourhoods become a new planning action space. This is worked out within a framework of activism for the activation of local resources and establishes spatial organizational principles.

Under the frame of sustainable development, universities (planning and built environment) and research institutions have adopted new collaborative teaching and research methods to knowledge production [Lange, Harding and Cahill-Jones, 2019 ]. Collaborative spaces have been acknowledged as a key driver to a successful transition design among institutions, networks and civil society to develop and learn actual social requirements [Helfrich and Haas, 2012 ]. However, in knowledge-making spaces, these institutions are often facing challenges like to maintain dialogue spaces with experts, local groups, urban activist networks and city administrations and meeting increasing performance expectations that are critical to decision-making at comparable European and global assessment levels.

2 Open end-adventure

The growing number of bottom-up spaces has recently challenged policymakers, planners and architects on how to best support these initiatives. In addition to state-led new governance models and participation opportunities, a new generation of city entrepreneurs seeks to define their work and living environments to meet their needs and aspirations in a collaborative and commons-based way. Particularly in this field, international discourses are presenting the arrival of private investors as key players in urban development. The simultaneous withdrawal/absence of the state has led to a more complex network of participating actors and conflictive urban development patterns in various forms, in which strategies to guarantee the influence of societies’ interests for space productions are needed.

Empirically, from our study a variety of projects have been registered in which co-production patterns have been developed: ephemeral spaces, housing, sustainability, urban regeneration. For this development, it seemed pertinent to focus on the four fundamental dimensions of co-production (Actors, access processes, spaces). At the same time we can conclude that these patterns are the facilitators and key adjusters. The essence is that it is worth to achieve in the future a greater insertion of the idea of co-production in projects that have the urban environment as a field of application. In the existing diverse and dynamic urban contexts, co-production arguably has innovative potential to challenge the traditional spatial planning framework, through the involvement of a large number of new players, personal commitments, new ideas, practices and experiments. However, following the growth of the concept, (international) research debates and project frameworks need to be concerned with the following — as this project, the both authors are collaborating on, is formulating: to understand the interdependencies and benefits of different forms of co-production development, its functional structure on various interdependencies from local to the macro level. Especially, with regard to its social-spatial processes and in particular in — or exclusionary effects that they can produce, as this seams still not clearly understood from the current researches.

References

-

Alfaro-d’Alençon, P. and Bauerfeind, B. (2017). Kooperative (urbane) Praxis — Räume, Akteure + Wissenbildung in der Stadtentwicklung. Ludwigsburg, Germany: Wüstenrot Stiftung.

-

Aravena, A. and Iacobelli, A. (2013). Elemental: incremental housing and participatory design manual. Bilingual edition. Ostfilder, Germany: Hatje Cantz.

-

Blomley, N. (2016). ‘The right to not be excluded’. In: Releasing the commons: rethinking the futures of the commons. Ed. by A. Amin and P. Howell. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Routledge, pp. 89–106. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315673172-6 .

-

Brownill, S. and Parker, G. (2010). ‘Why bother with good works? The relevance of public participation(s) in planning in a post-collaborative era’. Planning Practice & Research 25 (3), pp. 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2010.503407 .

-

Coaffee, J. and Healey, P. (2003). ‘“My voice: my place”: tracking transformations in urban governance’. Urban Studies 40 (10), pp. 1979–1999. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000116077 .

-

De Angelis, C. (2017). ‘A crowdfunding campaign for the acquisition of the Casa del Pescatore “Bene Comune”’. LabGov.org . URL: http://www.labgov.it/2017/08/12/a-crowdfunding-campaign-for-the-acquisition-of-the-casa-del-pescatore-bene-comune/ .

-

Dellenbaugh, M., Kip, M., Bieniok, M., Müller, A. and Schwegmann, M., eds. (2015). Urban commons: moving beyond state and market. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783038214953 .

-

Gidwani, V. and Baviskar, A. (2011). ‘Urban commons’. Economic and Political Weekly 46 (50), pp. 42–43.

-

Gruber, S. and Ngo, A. L. (2018). ‘The contested fields of commoning’. In: An atlas of commoning: places of collective production. ARCH+. URL: https://www.archplus.net/home/english-publications/an-atlas-of-commoning/328,0,1,0.html .

-

Harpham, T. and Boateng, K. A. (1997). ‘Urban governance in relation to the operation of urban services in developing countries’. Habitat International 21 (1), pp. 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-3975(96)00046-x .

-

Helfrich, S. and Haas, J. (2012). ‘The commons: a new narrative for our times’. Heinrich Böll Stiftung 15.

-

Kuhn, G. (2016). ‘Planungslabor in Kooperation mit Wüstenrot Stiftung’. In: Ephemere Stadtentwicklung. Berlin, Germany: DOM-Publisher.

-

Lacaton, A. and Vassal, J. P., eds. (2015). Lacaton & Vassal 1993–2015. El Croquis n 177–178 monograph. Barcelona, Spain: Editorial GG.

-

Lange, B., Harding, S. and Cahill-Jones, T. (2019). ‘Collaboration at new places of production: a European view on procedural policy making for maker spaces’. European Journal of Creative Practices in Cities and Landscapes 2 (2), pp. 63–81. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2612-0496/9556 .

-

Lepratti, C. and Alfaro-d’Alençon, P., eds. (2018). Does effective planning really exist? Freiburg, Germany: Syntagma Verlag.

-

McFarlane, C. (2011). Learning the city: knowledge and translocal assemblage. Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444343434 .

-

Miraftab, F. (2009). ‘Insurgent planning: situating radical planning in the global south’. Planning Theory 8 (1), pp. 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095208099297 .

-

Nesti, G. (2018). ‘Co-production for innovation: the urban living lab experience’. Policy and Society 37 (3), pp. 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1374692 .

-

Ostrom, E. (1996). ‘Crossing the great divide: coproduction, synergy and development’. World Development 24 (6), pp. 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750x(96)00023-x .

-

Simone, A. (2004). For the city yet to come: changing African life in four cities. Durham, NC, U.S.A.: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822386247 .

-

Torrent, H. (2020). ‘Resilience and co-production: conserving modern housing in Chile’. In: Docomomo International Conference Proceedings . Tokyo, Japan: Docomomo Japan.

-

Turner, J. F. C. (1976). Housing by people — towards autonomy in building environments. London, U.K.: Marion Boyars.

Authors

Paola Alfaro-d’Alençon is an Architect and holds a doctoral degree in urban studies. She started last year as a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG)-Research Fellow and associate Professor to the TU-Berlin, Institut für Architektur. Visiting professor since 2016 for urban design and theory at the Università degli Studi di Genova. Urban research and design practice in the Berlin based U-Lab studio. Works with national and international organizations in consultancy for urban planning, governance processes and climate change frameworks. Founding member of the Urban Research and Design Laboratory (U-Lab, release 2012) at the TU-Berlin, awarded with the “Label Nationale Stadtentwicklung” from the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development. Co-author of several publications as Ephemere Stadtentwicklung (DOM Publisher Berlin, 2016) and co-editor or “Emergent Urban Spaces — A Planetary Perspective”, The Urban Book Series, Springer Verlag, London, Berlin. E-mail: alfarodalencon@tu-berlin.de .

Horacio Torrent Schneider. Architect UNR, Argentina, 1985. Magister in Architecture PUC Chile, 2001; Ph.D. UNR, 2006. He has developed research on modern architecture at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, at the Getty Institute for the Arts and the Humanities, at the National Gallery of Arts in Washington, and as Gastwissenschaftler at the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut in Berlin. Has taught at universities in Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, México, Perú and Spain. Currently Tenured Professor of Architecture at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. E-mail: htorrent@uc.cl .