1 Introduction

What does it mean to “see the ‘seeing’ of others” [Kato, 2014] through the exchange of photos on mobile devices across two countries, when participants may never meet each other in person? Social science researchers across China and Germany associated with the Urban-Rural Assembly (URA) project have explored this question by experimenting with a (post)digital ethnographic method for conducting research across borders in the context of mobility restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a project funded by the German government’s Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), URA has deployed interdisciplinary teams of researchers, policymakers and communities to develop future scenarios for the sustainable urban-rural transformation of planning and governance in China’s Taizhou region since 2019. These processes are operationalised through two urban-rural ‘Reallabore’ or Living Labs (LLs) in Huangyan, China and one LL in Thüringen, Germany, as spaces which offer experimental platforms for research and development in direct collaboration with local actors.

LLs can be defined as “user-centred, open innovation ecosystems based on a systematic user co-creation approach, integrating research and innovation processes in real-life communities and settings” [Ruijsink & Smith, 2016]. The work of LLs is typically carried out with participants in real-world environments to foster collaborative experimentation, learning and innovation that can be adapted for other locations and contexts [Higgins & Klein, 2011; Steen & van Bueren, 2017; Ruijsink & Smith, 2016; Franz, Tausz & Thiel, 2015]. Emphasis is directed on placemaking as a local arena for social learning and exchange [Laborgne et al., 2021], in which “policymakers, researchers, businesses, service providers, citizens and other stakeholders work together to develop and test new ways to solve problems in a specific geographic region” [Robust, 2021].

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across China and Germany from 2019–2022, physical engagement between researchers in Germany and the ‘real-world’ field sites of URA’s two LLs in Taizhou became increasingly difficult. Researchers thus set up a prototype in the form of a WeChat (Weixin 微信) group to experiment with new approaches for connecting with participants of the three LLs across borders — a liminal space that in turn became its own kind of LL for cross-sectoral experimentation during a period where physical exchange between stakeholders of the Chinese and German LLs was not possible. Informed by digital ethnographic methods like photovoice [Nykiforuk, Vallianatos & Nieuwendyk, 2011; Sutton-Brown, 2014], individuals located in and around the LLs in Huangyan-Taizhou were invited to engage in a curated exchange of photos with researchers involved in the URA project, with each side sharing artifacts of everyday experiences — from commutes and panoramic views to intimate moments at home.

In this paper, we explore how social network platforms like WeChat can be used to understand socio-spatial practices in selected study areas (in this case, LLs) by experimenting with a two-phase method for postdigital interaction between participants where encounters in a physical field is not possible. Our method integrates a variety of postdigital ethnographic approaches, including photo exchanges, informal chatting and interviews, along with ephemeral data collection on the socio-spatial practices and texture of everyday life in urban-rural LLs. We work in particular with the prototype model which is commonly implemented in user-centred design and DIWO (Do-It-With-Others) settings in order to build a preliminary version of a product, test it with users, iterate according to feedback, and rework it to suit their needs [Catlow & Garrett, 2019; Camburn & Wood, 2018; Kera, 2012].

In the following sections, we will explore how the process of building and maintaining a WeChat photo-sharing group enables the concept of a LL as a site of experimentation and innovation amongst diverse stakeholders to be transferred, developed, and evaluated across both physical and virtual environments. Within a WeChat group (which in practice becomes its own kind of LL, as we will outline), emergent imaginaries and life experiences are casually exchanged. WeChat thus becomes another potentially helpful LL tool for exploring how sustainable future scenarios can be investigated and co-imagined alongside local actors, policymakers and scientists. Our experimentations with the method also provide a wealth of practical insights for other kinds of ethnographic LL research that require close interactions with participants working in fields that have been limited by unexpected circumstances, from public health crises and natural disasters to border lockdowns. This offers special value for research on, and with, digital platforms based in China.

The paper begins with an overview of the theoretical basis for conducting postdigital ethnographic research within the project’s urban-rural LLs, and an explanation of how our two-phase method for LL interaction was applied in practice through the URA WeChat group. In the findings section, themes which emerged from the photos shared within the group are discussed, along with an analysis of interactions between LL participants. In the discussion that follows, we offer methodological reflections on the limitations, biases and ethical concerns of the prototype. In conclusion, we suggest four design principles for how our WeChat method for postdigital exchange with participants might be implemented in other kinds of projects working with LLs where physical co-location is not possible.

2 Theoretical framework and literature review

2.1 (Post)digital ethnographies in hybrid virtual/physical environments

In constructing our methodology, we are informed by theoretical approaches to digital ethnography as a form of making place and building connection in post-screenic and/or postdigital environments, where a kind of ‘immersive cohabitation’ between users emerges through cross-platform interactions between devices, softwares and algorithms [Bluteau, 2019]. By digital ethnography, we refer to the methodological grab-bag of approaches used to conduct empirical research in hybrid virtual/physical environments. These approaches adapt traditional ethnographic methods used to examine human and non-human relations across the social sciences (including participant-observation, interviewing, and immersion in a field of study) to build an understanding of field sites which are algorithmically-mediated.

Because the aim of digital ethnographic approaches is to emulate physical forms of ‘walking through’ field sites without the use of a physical body, digital ethnographies typically feature mobilities particular to screenic forms, such as “fingers moving across media device surfaces […] navigational flows through nested app infrastructures, and the different kinds of habitating, narrating and reflecting that digital social media [and email, chat, video calls, etc] allow” [Møller & Robards, 2019, p. 96]. While digital ethnographic methods initially explored what it meant to be ‘virtually human’, and dichotomised field sites as either ‘online’ or ‘offline’, contemporary postdigital approaches emphasise the environmental hybridities of ‘post-screenic’ worlds, where digital devices like mobile phones, wifi networks and Internet of Things (IoT) sensors are increasingly enmeshed in, and integral to, the mundane practices and communications of daily life [Bluteau, 2019; Boellstorff, 2010].

These developments are especially evident in technologically-advanced nations like China, where social network platforms (SNPs) like WeChat are used for a wide variety of essential administrative and financial functions, expanding the reach of such platforms beyond their original ‘passive usage’ of casual chatting on mobile phones, and into the everyday structural functioning of homes, schools and workplaces [S. Chen, Shao & Zhi, 2019]. These developments illustrate how algorithms and software can play a role in ‘making space’, by reframing the power-geometries which structure (and are in turn structured by) ever-evolving flows of goods, services and actor-networks, endowing social actors with uneven access to agency, capital and mobility across multiple geographies [Braybrooke, 2019; Dodge, Kitchin & Zook, 2009; Massey, 1993]. Postdigital communication platforms like WeChat provide ideal field sites for researchers to examine these flows of power and influence in China, where grassroots organising, tactical co-creation and resistance co-exists alongside increasing consolidation, surveillance and control [Braybrooke, 2022].

2.2 Accessing physical fields through postdigital Wechat groups

Postdigital traces such as photographs, audio, text and video clips generated from specific geographic locations have been formative in providing scientific researchers with access to local knowledges about urban-rural experiences [Kwan, 2002]. Geocoded data shared on SNPs is used in imagining the “life maps” [Alibrandi, Thompson & Hagevik, 2000], “body inscriptions” [Laws, 1997] and “spatial stories” [De Certeau, 1984] of everyday life. By establishing a WeChat group which purposely invited LL participants from the URA project’s research region, our methodological experiment was intended to enable researchers to be able to ‘see’ these socially embedded spatialities by engaging with the ‘seeing’ of local participants.

The WeChat group as an ethnographic site has been explored in a variety of settings [Sun & Yu, 2020; Zhou & Xiang, 2021; D. Wang & Liu, 2021; Qian & Mao, 2021; Nam, Weber, Liu & English, 2022]. To build an understanding of feminist actions in China, for example, D. Wang and Liu [2021] collected empirical data through day-to-day participation in a WeChat group of feminist activists. By maximizing interactions with Chinese feminists in chatrooms, the researchers managed to build close connections before visiting the field [D. Wang & Liu, 2021]. In another project aimed at examining the educational role of WeChat groups in processes of ‘citizen-making’, researchers conducted participant observation in 45 politically-oriented WeChat groups across China, and analysed data collected from group discussions [Sun & Yu, 2020].

Scholars have also reflected on the challenges they encounter when using WeChat groups as a method [e.g. D. Wang & Liu, 2021; Sun & Yu, 2020; Nam et al., 2022]. China’s Internet censorship and surveillance are recognised ethical issues which can put both researchers and participants at risk [D. Wang & Liu, 2021; Nam et al., 2022]. Researchers who act as ‘embodied subjects’ participating in the everyday lives of online fields, as argued by digital ethnographers, should be acknowledged as “integrated dimensions of the research process” [Kozinets, 2010; Bengtsson, 2014]. In her research on migrants’ social and economic practices using a mixed approach of online and offline methods, Zani [2021] notes that digital ethnography should be designed and performed in dialogue with offline observations. She suggests that only by looking at both spheres together can a comprehensive view of social phenomena be gained [Zani, 2021]. Traditional ethnographic methods like in-depth interviews are considered an important supplementary method for interpreting the fragmented data gathered from WeChat groups [Sun & Yu, 2020; Zhou & Xiang, 2021]. Moreover, the representativeness of the data gained from SNPs should also be questioned, as digital ethnographies may exclude people without sufficient access to (or knowledge of) digital platforms, mobile phones, and the Internet, such as elderly groups [Y. Chen, Sherren, Smit & Lee, 2021].

Nevertheless, the power of postdigital ethnography should not be underestimated. D. Wang and Liu [2021] note that digital ethnographic approaches conducted through social media do not change the basic principles of traditional ethnographic methods, as researchers are still immersed in their research subjects’ digital sites and day-to-day interactions. The establishment of a WeChat group can thus enable researchers to overcome the time and cost constraints of field trips and travel restrictions, while also providing opportunities to cultivate lasting relationships with field informants across digital and physical space.

2.3 Let the photo speak: image-based participatory research

Photos can provide evidence of additional insights, local textures and lived experiences in comparison with other texts [Y. Chen et al., 2021], in ways that transcend language barriers and borders alike [Jurgenson, 2019]. Moreover, photos can reveal insights into the lives of the individuals who take them through the angles they choose to shoot from and the items they decide to include and not to include in the frame. Therefore, reading photos beyond their frames can allow interpreters to gain an insight into the external narrative and mental space of photo takers themselves [Sturken & Cartwright, 2019; Banks, 2018]. Furthermore, photos can reveal dynamic underlying meanings of objects and events, as the meaning of an image is not limited to the information and emotions it carries when it is captured, but can also extend to what happened before and after, depending on its post-event interpretations [Finn, 2012].

How can photos speak? Photovoice, a participatory ethnographic method that has gained popularity in social science research over the past two decades, is “a process by which people can identify, represent, and enhance their community through a specific photographic technique” [C. Wang & Burris, 1997, p. 369]. To conduct photovoice research, the researcher invites participants to take photos of their neighbourhood, city, or private spaces, and capture the moments, landscapes, people, buildings or objects which they perceive as meaningful in relation to a specific research question; the researcher then asks the participants to describe the photos they take, individually or in a focus group, to promote critical dialogue and knowledge exchange about the spaces captured within the photo [C. Wang & Burris, 1997; Kong, Kellner, Austin, Els & Orr, 2015]. The use of photovoice to study the impact of urban transformation on people’s everyday lives is increasingly considered to be impactful in engaging vulnerable groups to play an active role in the research in an accessible way [Meenar & Mandarano, 2021]. By capturing and discussing photos, participants can gain a deeper understanding of local issues, and voice out their valuable local insights to researchers [Kong et al., 2015]. Photovoice can also be used as a valuable vehicle for building trust and capacity within a community, as well as to convey community messages to upper-level decision makers, making it an effective tool for participatory urban-rural planning [Meenar & Mandarano, 2021].

While informed by the photovoice method, our WeChat photo-sharing prototype had its own distinct features. First, individuals were placed together in one chatroom, and asked to share photos in the group as they went about their lives. This meant the production and sharing of photos was not a completely independent activity free from conscious (or subconscious) group influence. Second, the interactive features of the WeChat platform enabled researchers to observe and exchange with informants in real-time or with a short delay, which is typically not in line with the photovoice approach and its “capture first, discuss later” process. As suggested by Bengtsson [2014], direct interaction with research participants is more valuable for ethnographers when gathering first-hand data, instead of solely being used for observation. Third, as part of the development of our methodology, an initial phase was introduced in which group members were not able to send text messages at all, with the aim of overcoming language barriers and building initial connections and trust with local participants. With these distinctions, our WeChat photo-sharing approach is especially applicable for postdigital ethnographic studies in fields faced with similar cross-cultural settings, where participants are located in distant or difficult-to-access research regions.

3 Research context and methodology

3.1 SNPs as essential sites of intercultural exchange during global crises

Amongst other purposes, social network platforms (SNPs) have become influential modes of communication worldwide for relaying everyday experiences and social worlds. SNPs such as Facebook and LinkedIn operate as “web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system” [Boyd & Ellison, 2007, p. 211]. The Chinese SNP WeChat is free of charge, and supports everything from instant messaging, audio and video calls to social media, mobile payments, ride hailing and gaming. It also links to medical, retail, security and fast delivery services, among other functions that facilitate everyday life, which also increases the frequency and range of daily public access to such services. According to Xiaolong Zhang (president of WeChat Business Group), “Every day, 1.09 billion users open WeChat and 330 million make video calls; 780 million users enter Moments; 360 million users read official account articles and 400 million users use Mini Programs. WeChat Pay has become a daily necessity, like a wallet” [Tianyang, 2022]. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the postdigital interactions of platforms like WeChat played an increasingly essential role in supporting social encounters in times of crisis, becoming ever more essential for maintaining connection across borders. In 2022, the number of WeChat users reached 1.2 billion, with 78% of China’s population aged 16–64 linked to the platform [Statista, 2022].

Postdigital communication became especially essential for the URA project, due to its reliance on local knowledge about everyday experiences of urban-rural transformation across the physical fields of its three LLs. The hypothesis of URA is that participatory and actor-oriented urban-rural research and practice represent key levers in building resilient and sustainable future developments. To do so, the interdisciplinary URA research consortium collaborates across borders to address context-specific sustainability challenges through strategic spatial planning methods such as the Raumbild approach. Raumbild is a method established in the German context as a participatory planning process involving multiple actors, and is the nucleus around which each of the project’s LLs unfurls over time. The project’s three selected urban-rural LLs are its central case studies as well as its platforms for experimentation, serving as local research and development anchors. Researchers associated with the LLs thus decided to integrate the WeChat platform into the URA project’s research methodology when it became clear that physical engagement with the two LL’s in China would not be possible for German researchers for an extended and undetermined period of time.

3.2 Process: WeChat group setup and phasing

The WeChat group ‘URA 照片分享群’ (Urban-Rural Assembly Photo Exchange) was launched in prototype form to the public in February 2022 after several months of planning, with the intention that its methods and approaches would evolve over time based on user feedback. The authors of this paper acted as ‘guardians’ of the group, and maintained its liveliness by exchanging at least three photos per week with participants. After an initial phase of testing the group internally with researchers in China and Germany, Phase 1 of the prototype ran from February 2022 to October 2022, and involved participants with connections to the project’s two LLs in the case study region of Huangyan-Taizhou in Zhejiang province — named Beiyang Town and Smart Moulding Town.

3.3 Participant selection, engagement and feedback

Participants were invited from across the LL communities that the project’s researchers had connected with during previous fieldwork in Huangyan in 2019 and 2022. This included the students and researchers of local partner universities, migrant workers, villagers, farmers, policymakers and entrepreneurs. The authors crafted an introduction text in English and Mandarin, and invited participants to freely share photos from their everyday lives that they found interesting, inspiring or funny, giving examples of common activities such as going to work, cooking, playing and relaxing. The authors explained that the photo exchange group was an image-only environment which welcomed photos, videos, GIFs and stickers without words. The intention was to offer simple visuals that enabled initial engagement across languages and cultures.

After running the group for eight months, the authors conducted a survey to garner feedback from participants in order to modify the method for the next phase. At this stage, the survey questions were mainly designed to understand group dynamics. Adjustment strategies were expected to be made according to the survey responses to foster more active participation in Phase 2. The following questions were asked:

-

What’s one thing you like about the group so far?

-

What kinds of photos do you like to share in the group? What kind do you like to see?

-

Do you feel restricted in sharing photos in the group? If so, why? What do you think would help people feel more comfortable to share photos?

-

Does photo sharing help you to establish any sort of connection with other people in the group? Would you like to have further communications with other group members?

9 participants responded to the survey, which helped the authors to identify key limitations, concerns, and opportunities, and integrate them into Phase 2.

3.4 Iterating WeChat engagement, from Phase 1 to Phase 2

In Phase 2, four major adjustments were made according to the learnings of Phase 1. First of all, more diverse participant communities were invited to the WeChat group alongside encounters in the field of a URA colleague who had managed to travel to China to conduct fieldwork in September 2022 despite ongoing travel restrictions. This increased the group size from 23 to 41 members. Second, the ‘images only’ principle was removed to allow informal chatting between group members, such as asking questions and commenting on images exchanged. WeChat has a translation function which allows participants to write in English or Chinese, enabling participants to immediately translate messages and fostering smooth communication among those responding in different languages. Third, participation in a newly gamified format was incentivised with a small monetary reward of 10–15 Chinese Yuan (approximately 1.30–2.00 Euros) through WeChat’s virtual ‘red pockets’ function. Last, a series of calls were curated and launched which invited participants to share photos relating to a specific, simple theme each week.

The themed calls were designed around three purposes: (1) Achieving more active participation; (2) Gaining participant photo responses which correlated more closely to the project’s research themes; and (3) Limiting the potential for shared content to highlight social inequalities amongst participants. Weekly themes included but were not limited to:

-

Places you like to spend leisure time

-

Your favourite green spaces

-

A place where you have a special memory

Rapid urbanisation in Huangyan has fostered a decline of ecological and agricultural spaces, while the industrialisation of villages has drastically changed people’s dwelling types and locations, lifestyles, and forms of employment. Therefore, the choice of images corresponding to these guided themes were expected to bring important insights about how people used public spaces and which places carried special meanings to them. Studying everyday practices and spaces offers valuable reflections of the evolving social dynamics and power relations associated with space and place, particularly as “all social relations become real and concrete, a part of our lived existence, only when they are spatially ‘inscribed”’ [Lefebvre, 1991, p. 46]. Thus, the exchange of everyday spatial images-in-common is crucial to co-imagining future scenarios for more socially and environmentally-just development.

3.5 Data collection and analysis

During this two-phase process of prototype iteration, the authors collected image and textual data from the WeChat group, recorded their interactions with local participants through field notes of digital participant observation, and conducted surveys and one-to-one interviews with research participants. The image and textual data were then analysed through a process of thematic coding. In order to reduce the subjectivity of the analysis, each author of the team interpreted and coded the images independently before a collective discussion and analysis. The field notes, survey results, and interviews have been incorporated in our reflections on the two-phase prototype in urban-rural LLs, and are presented in the following sections.

4 Research findings

In this section, we begin by presenting the kinds of photos which were shared in the WeChat group during the curation phase and under the guided theme calls, and the major themes that emerged. We then shed some light on the types of photos that evoked lively group reactions. The characteristics of these images are showcased regarding their spatial and emotional meanings to the photo takers, which have potential to serve as crucial references for regional development pathways. In the third part, we discuss how using images as a communication medium fostered participant interaction in ways that transcended geographic and cultural boundaries. This is followed and complemented by a critical observation of the differing perspectives and understandings of the images that were shared in the group. The section concludes with a practical discussion of how researchers and field participants interacted, which provides useful information and guidance for conducting postdigital research in other kinds of field sites.

4.1 Central themes emerging from participant photos

In order to create a friendly and welcoming atmosphere that engaged local participants of the LLs, researchers involved in the WeChat group proactively shared their own daily lives during the first two weeks of Phase 1, with images covering broad geographic locations including Huangyan, Germany, Thailand, and more. The images aimed to demonstrate the type of content the group was aimed at, with varied subjects such as spaces like intimate indoor living spaces to public parks, and from food to art exhibitions, representing diverse everyday activities of working, traveling to work, sightseeing, and socialising. Encouraged by this, a few local participants in Huangyan started to share photos. The images shared by local participants during this phase included subjects such as city landscapes, urban parks, and food.

In Phase 2, under the guiding theme “my favorite green spaces”, Jiufeng Park (one of the oldest urban parks in Huangyan), Yongning Park (an urban park located at the city centre with a modern design), and Changtan Reservoir were among the most frequently shared green spaces in the group. One group member proudly introduced Jiufeng Park as an “AAAA tourist spot” (a high national ranking in China) and invited group members to visit. Living near the park and visiting it daily, his photos covered different times of the day which were highly valuable to the researchers in understanding the use of space at different times. Another group member from Huangyan took the initiative to express his concern about the recent drought by sharing a photo of the Changtan Reservoir with a low water level. This sparked a discussion amongst participants which offered further insight into the local environmental concerns held by residents of the region. Under the theme “places with special memories”, photos shared generally consisted of local cultural sites, such as scenes of an ancient pagoda on the mountain or a grotto decorated with colourful lights. The tactic of guided photo sharing thus proved to be an efficient tool for increasing participation and achieving more targeted outcomes than in Phase 1.

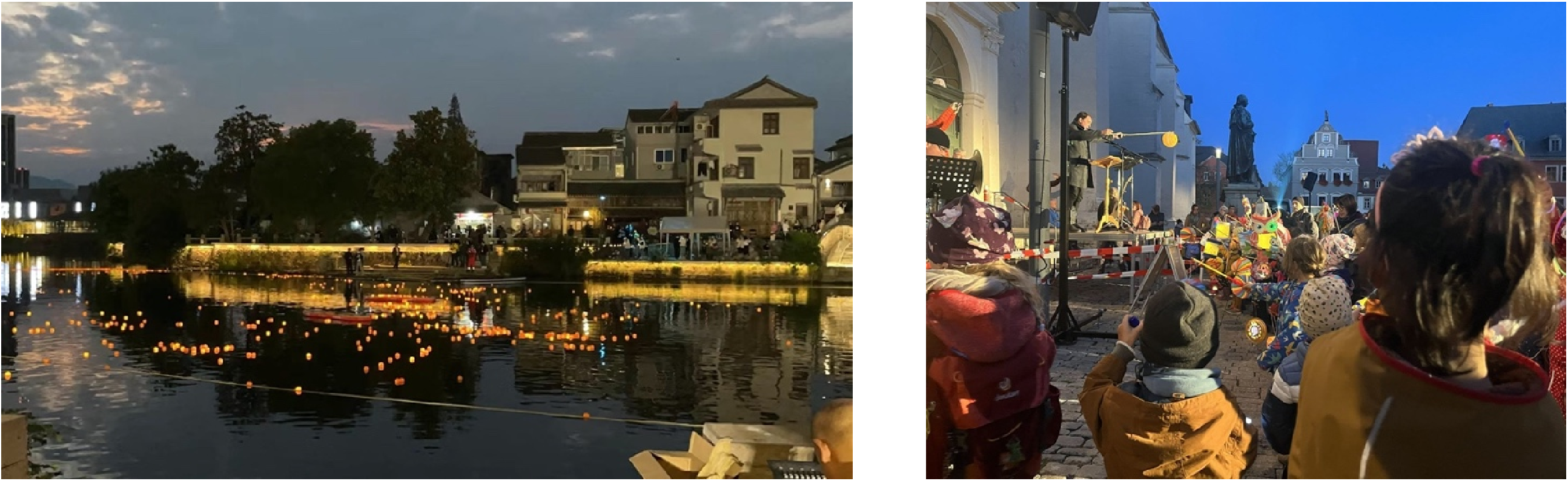

Other themes that emerged from the photo sharing outside of the themed calls could be categorised into three primary groups: landscape and architecture, moments of everyday life, and socio-spatial practices. In the theme of landscape and architecture, photos such as urban or village views, buildings with interesting designs or shapes, traditional village houses and temples, and cultural halls were captured. Participants frequently shared attractive moments from their everyday lives, such as a beautiful sunset and rainbow to a trace of a plane in the sky. Under the theme “socio-spatial practices”, diverse activities were presented in the shared photos, including children playing in the park, villagers washing clothes at the riverside, urban festivals, markets, COVID-19 test sites, eating in a restaurant, religious practice in the temples, shopping, collecting flowers, and many more (Figure 1). Photos in this category offered an extremely valuable window for the project’s researchers to get a glimpse of everyday life in the physical field of Huangyan. They also served as important documentation of events that carried their own specific space-time meanings. For example, as the Zero-COVID policy intensified across China during Phase 2, many local participants shared photos of their “daily PCR test” in the group. Other season-specific events, such as the yearly Orange Festival in Huangyan and the blossom of the osmanthus tree, also offered rich insights and texture in terms of local cultural and social practices.

4.2 Place identities and their emotional attachments

The photos that sparked the most lively group discussions were scenes of urban festivals in Huangyan and Germany. A citizens’ art festival and an orange festival were showcased by people living in and around the LLs in Huangyan. Their photos featured various objects and activities, such as an orange-themed statue, people participating in a square dance, the speech of a heritage preservation professional, shimmering orange lights on a river, or a coffee stall at the open market (Figure 2). Discussions stimulated by these photos generally reflected positive sentiments, indicating that participants appeared to be proud of sharing the local rituals of these personally or culturally meaningful events with international audiences. In addition, photos with identifiable place characteristics, such as an LED facade showing the name of Huangyan, local plants, city museums or traditional architecture, were commonly shared by local participants. Such photos carried a strong place identity and local meaning, and signified important representations of participants’ sense of belonging and place-attachment to their local regions. The selective representation of spaces also demonstrated the types of activities or spaces that were perceived to be worthy of showcasing to outside audiences due to their positive representation of the local area.

4.3 Photo exchanges that stimulate intercultural dialogues and connections

As the WeChat group progressed, its conversations increasingly revealed how photos and the act of exchanging them can be powerful tools for starting dialogues across geographic borders and involving their respective cultures. URA researchers who had been to Huangyan recalled fond memories of Huangyan after seeing photos shared by locals. The discussions following these photos demonstrated a favourable view of the local area in Huangyan, which helped to nurture a positive atmosphere in the group, and encouraged further participation. Images of attractive scenery and ‘beautiful moments’ shared in the group were celebrated and encouraged by other participants through words and emojis. While some photos shared did not relate directly to the research questions, they played an important role in promoting dialogues between participants, bringing them closer to each other through increased trust and familiarity.

Just as the process of a photo’s inclusion suggests various motivations and personalities of its author, it also provided possibilities for participants to forge connections with each other within the WeChat group. One group member reflected:

“I like to share photos which are beautiful to me, like flowers or landscapes, or something that is related to my emotions, like places, food, views, or when I had a good time with my family. I want to see something which can make me happy.” — Survey respondent, Chinese in Germany

Another participant revealed:

“If you like the photos people share, then you are more willing to get to know more about him/her and their life stories… I would like to have further communication with group members who I do not know. Their photos make me curious about their life stories.” — Survey respondent, Chinese in Germany

Through communications like these in the WeChat group, researchers and local participants who could not meet in person cited how they had gained an intimate view into each other’s unique life experiences and outlooks across the borders of China and Germany.

4.4 Photos that reveal varying perceptions and meanings of space

The participant observations conducted in Phase 1 and 2 also enabled the project’s researchers to reflect on their own biases. While the photos shared by researchers were primarily old village houses, temples, and informally planted vegetables — scenes that were interesting for them when they were able to investigate the local identity in the physical field (Figure 3), photos shared by locals mainly presented modern architecture, urban festivals, and urban parks decorated with lights. It could be perceived that locals preferred to present a modern and urban image of Huangyan in the WeChat group, rather than photos that related to its rural characteristics (Figure 4).

Another example could be seen when a researcher shared a photo taken in Huangyan, showing vegetables planted at the riverside beside a modern real estate compound, to which a local participant commented: “Green field, fresh vegetables”. On the other hand, the image was discussed amongst the researchers as a manifestation of the ongoing conflicts between rapid urbanisation processes in the region, and the rural lifestyle and practices of villagers. This observation reflects the ways that the production of local places and their (social) concepts are perceived and interpreted distinctively by individuals according to their own personal experiences, contexts and purposes. It also reminds us that we can not always take such concepts for granted without embedding the importance of space itself as a social production within particular time-space contexts.

4.5 Interactions with, and among, local participants

During the initial phase, the researchers and students who had joined the group through the URA project were more active in sharing photos than in Phase 2. This could have been the result of a better shared understanding of the purpose of the WeChat group, the already-established familiarity between project organisers, and their cultural openness to participating in an international environment. The interaction with locals increased considerably when an URA researcher who had the opportunity to travel to China and be present in the field started to share photos from Huangyan that were recognisable by the local participants. People started to get involved when they saw photos of places they felt familiar with or had something to compare with from their everyday lives, such as farms, cityscapes, and street views. Our surveyalso suggested that participants felt alienated by photos that were too different from what they were used to.

In Phase 2, the group size increased, themed calls were introduced, and monetary incentives were provided. These adjustments significantly encouraged participation, while personal communication also increased through participants commenting on each other’s photos, and sending and receiving red pockets. However, the researchers also observed that many of the photos shared by participants did not necessarily correspond to the theme calls. One participant expressed that the themes limited her freedom of sharing the types of photos she liked.

5 Discussion: critical reflections on limitations, biases and ethics

5.1 Trust

During the 8 months of Phase 1, the WeChat prototype approach was largely successful at creating an informal and friendly professional community of LL stakeholders. The researchers working at academic institutions in China and Germany actively shared photos and interacted freely. However, the phase only achieved limited participation from the group’s non-researchers, such as students and farmers, among other local actors. The main reason for this appeared to be a lack of trust. The researchers’ inability to establish personal connections in the physical fields inhabited by local participants made it difficult for many participants to feel comfortable joining a group full of strangers only known to them through a WeChat name and a virtual avatar image.

Some participants cited finding the instructions of the group too vague, and others worried about personal privacy and the security standards of the WeChat platform. More than one participant from Germany considered the surveillance and data protection of Chinese platforms to be a real concern, and cited being wary of sharing their intimate moments. Moreover, a local participant from Huangyan expressed that he felt unmotivated in Phase 1, because the group size was too small. A limited number of messages (in image format only) in the group meant that photos often seemed to stand on their own, with many of the participants seeming to prefer observing these first, and then decide later whether and how to participate in group activities. In their digital ethnographic research on WeChat, Sun and Yu [2020] also observed that many people chose to be silent in public WeChat groups because they joined to “lurk for information” (4). During Phase 1 of our WeChat group, it was difficult for new group members (lurkers) to grasp the characteristics and narratives of the crowd, which consequently discouraged further participation.

5.2 Bias

The free-sharing model of SNPs like WeChat should not be considered unbiased. We observed a tendency amongst participants to share similar images as those shared by others. For example, after a researcher shared photos presenting cityscapes and architecture, local participants responded with similar photos (Figures 5, 6). This indicates that images without text captions carry the potential to create their own dialogues. However, these dialogues can potentially influence participants’ ways of observing their own living environments. In an interview, one German participant explained how he had decided to not share certain content such as images showing people’s faces, because he had not seen similar content shared by others in the group.

The group dynamics also affected what kind of photos were shared, due to participants coming from diverse social, cultural, geographic, and economic backgrounds. While some participants celebrated this diversity, others seemed to feel disconnected. We observed that participants reacted more actively to images they already felt familiar with. Moreover, though local participants were randomly selected, there is a possibility that some of them might already know each other. As its size grew, the chance of meeting real-life acquaintances in the WeChat group also increased. Personal recognition and exposure between field participants are recognised risks in conducting ethnographic studies offline [Xiang, 2005; Stachowski, 2020]. In the WeChat group, recognising other people within the community coming from different social hierarchies or conflictual relationships might have reduced a willingness to share, while influencing the curation of shared content. In the long-term, an increased familiarity between group members may encourage interactions overall, but it can also limit the freedoms of sharing anonymously.

5.3 Language barriers

As previously mentioned, a key finding in Phase 1 was that a limited non-wordic postdigital format restricted communication possibilities. It was challenging for researchers to make theoretical concepts like ‘urban-rural’ and ‘socio-spatial’ clear to participants from diverse socio-cultural contexts who did not share a common language. In this format, there was no opportunity to explain anything more deeply or make full sense of the photos shared. In Phase 2, however, language barriers became more of a problem once text messages were also encouraged. Although participants were invited to use the WeChat translate function, smooth communication remained hindered by the app’s translation inaccuracies, as well as participants’ willingness and capacity to spend time translating along the way. Nevertheless, the inclusion of text-based messages did enable and stimulate more direct conversations between group participants, while helping them decipher together the meanings of photos shared.

5.4 Image interpretation

Another key finding from the two-phase prototype process was that while further guidance could constrain the freedoms of open sharing in the WeChat group, without it, shared content was too difficult to make sense of cross-culturally. It was often challenging to interpret the images without text annotations and geotags. Applying a postdigital photo-only approach to engage with LL stakeholders can thus result in outputs that are textured and multilayered, anchored in participants’ intimate experiences of local places, yet they also lack in local specificity and remain decontextualised. Without geotagging each photo, and without words to describe its context, many photos in Phase 1 appeared oddly universalised, the only clues to their origin coming from the location of their creator, and the cultural characteristics they appeared to represent. Several photos seemed to be from China, for example, but were actually from Germany or Thailand, while others appeared to have ‘European’ characteristics, but had been taken in China.

Are we really able to “see the seeing” of LL participants so distant from ourselves merely from the photos they present? While text and oral explanations are vital for third-person interpretation, they still do not enable researchers to understand the full meaning of an image, as the photo-taker might not address questions like “What is not included in the frame? why?” or “Who is your imagined audience?”. This may also pose challenges to the scale of research, as in-depth image analysis might not be suitable for large sample sizes.

5.5 Researcher positionality

During the two-phase approach, we found that a reciprocal relationship with local participants was a prerequisite for further inquiries such as one-to-one interviews, and thus adapted the method of participant observation [Kozinets, 2010] which requires active interaction with field respondents. However, researchers sometimes found it difficult to manage their own self-presentation and identity in the group. Compared with traditional ethnography, online and postdigital ethnography does not provide researchers with a clear in-group and out-group boundary [D. Wang & Liu, 2021]. A researcher in our team expressed that he found it difficult to separate professional and private spheres, as the “WeChat group is an intersection of both”. This dynamic especially affected the female researchers. For example, two female researchers revealed that when approached privately by male respondents from China in the WeChat group, they couldn’t decide whether they should stick to a professional attitude, or help the participant to feel more comfortable by following their lead in building the 1:1 connection alongside the group as a “casual online encounter”.

The ways that field participants were approached also had an impact on the kinds of reactions received. We observed that a participant might have a very different reaction to being approached by a Chinese researcher in Germany, a Chinese researcher in China, or German researchers in Germany. As an Irish researcher in Germany noted:

“As a foreign researcher conducting fieldwork in China, I often experienced a great deal of curiosity from people I met. As much as I was interested in people’s everyday lives, some people were equally curious about my life in Germany. I noted that in a few cases they didn’t display the same openness toward my Chinese colleagues.”

As an international research team, it is thus crucial for us to continue to reflect on our own positions as researchers, how we participate in the group, and how we approach participants online and in the field in ways that are equitable and caring for all involved.

5.6 Ethical concerns

Our WeChat group brought people from different social, cultural, economic, and geographic backgrounds together in a small, private virtual room across devices. This was different from other SNP interactions (including Facebook, Weibo and Instagram) due to members interacting with a small, cross-cultural group framed by research aims over a period of time (instead of the general public or their own social circles). This level of intimacy could sometimes provoke an emotional reaction in participants toward what they saw others posting. In our survey after Phase 1, a Chinese researcher reflected:

“I have been hesitant to invite my respondents from Huangyan into the WeChat group, as they come from very different social backgrounds compared with group members from Germany. Most are low-skilled workers who might have never traveled abroad. In our group they not only see the ‘seeing’ of others, but also their lifestyles. How would they feel when they see landscapes, food, and streets that are completely alien to them? How would they feel about a lifestyle they might not be able to afford, but have always longed for? What impressions would they get after seeing these strong visual materials, and how would they react to them? Would they hold back from sharing their own lives?”

Concerns like these from the project’s researchers highlight the ongoing importance of remaining sensitive to the evolving power dynamics between participants, and finding novel ways to moderate the kinds of images that may highlight these inequalities.

6 Conclusion — introducing four design principles for future research

In this paper, we have outlined how the co-creation of postdigital LLs situated in liminal spaces in-between physical fields can address the concerns of LLs which are faced with unexpected circumstances which limit their activities. We have explored in particular the possibilities of a two-phase method for gathering ephemeral data on socio-spatial practices in LLs where physical co-location with participants in the field is impossible or restricted. Our investigations have showcased the potential of transnational groups on SNPs like WeChat to be developed into a practical avenue for engagement with the everyday experiences of LL stakeholders from a distance, through photo exchanges (with and without a theme) and social texts. The local knowledges obtained helped us to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the social and physical fields of our LLs, while illuminating the potentials of engaging with relevant stakeholders and actors in ways that transcend brick-and-mortar spaces and places.

While the in-person exchanges between stakeholders of the project’s LLs in China and Germany became increasingly impossible due to the limitations of the COVID-19 pandemic, local engagement still proceeded at each LL in China and Germany through research and development activities conducted with local participants in-presence. This enabled the 3 LLs of the URA project to continue their real-world experimentation with sustainable development pathways in each nation, but not (and more importantly) the intercultural knowledge exchanges that had been planned in between them. By harnessing WeChat as a liminal space for these encounters in-between to emerge, the WeChat group became its own kind of LL, which focused on the possibilities of cross-border experimentation, by testing out innovative and creative approaches for working with web-based SNPs, in ways that worked around the physical limitations of LL participants.

Our findings also illustrate several prevailing challenges in experimenting with, and attempting to gather qualitative data on, liminal postdigital environments, including difficulties in forging trust and dealing with language barriers in intercultural settings; biases and limited choices for image-sharing in terms of familiarity versus anonymity; spurious interpretations of images without dialogue; and ethical concerns around the inequalities and power dynamics among participants, including the positionality of researchers themselves. These findings will be of particular use to research teams who aim to test out postdigital approaches to address physical LL limitations.

We will now summarise these important lessons gained in the field through four design principles, which present practical recommendations for future projects working with LLs in limited and/or blended virtual-physical settings.

Design principle 1: build trust first. It is essential that a relationship of trust and care between researchers and local participants, and amongst different types of participants, is cultivated through an ongoing commitment to long-term, sensitive and continuous engagement. Researchers engaging and embedding themselves within international LLs in postdigital settings must ensure to continually reflect on their own roles and situatedness in the group dynamics, and keep in mind their duty of care to the participants they invite to take part by regularly checking in with them.

Design principle 2: recognise bias. Bias inevitably exists and intersects with data derived from postdigital platforms. It emerges in association with the backgrounds and social hierarchies of participants and researchers alike, and frames the degree of familiarity versus anonymity experienced by the group. The knowledges gained are also affected by how people position themselves on a SNP, and the views they choose to express on different topics, impacted by social and cultural norms. Therefore, it is crucial for researchers to critically address such possible biases when interpreting the data. Identifying and attempting to look into the underlying reasons for this may also provide valuable insights into overlooked local knowledges, social dynamics, and micro-level social-spatial transformations that may not be immediately apparent if the data is merely taken at face value.

Design principle 3: give clear direction. It made a considerable difference to participant engagement in the WeChat group when a clearer structure was given to guide the photo exchange. Introducing concrete, themed calls relating to our research questions made it easier for participants to engage, and for observers to obtain focused local data to support interpretation. A more controlled sharing of content can also help to reduce the risks of exposing inequalities among participants. However, imposing themes may also limit the sharing of potentially valuable content not captured in the themes, while the lack of freedom may discourage some participants from engaging. The approach thus must depend on the research questions and aims of the researchers. Giving direction in Phase 1 of a WeChat group prototype can acclimatise participants to its aims, give participants more confidence to share their content in a more structured way, and build trust among group members, after which the conditions to employ more unstructured approaches can be improved.

Design principle 4: find a common language. Our experimentations with an image-only environment revealed challenges to interpretation which limited interactions among participants. The decision to include text-based messages comes with both opportunities and risks, and will depend on the nature of the group in terms of language and sample size, as well as the method of interpretation. Text annotations can open up far more direct and dynamic communication between participants, and foster potential for longer-term familiarity within the group. They also support the ability of researchers to achieve a higher level of insight into the meaning of the data from the perspective of participants. A more in-depth analysis of this information may only be appropriate for smaller sample sizes, however. Furthermore, in cross-cultural settings, language barriers and translation inaccuracies may inevitably emerge, which can affect the fluidity of communication among participants. Researchers should reflect on how this may affect engagement.

Can we really see the local ‘seeing’ of participants of LLs through photo exchanges on a WeChat group? As SNPs become an increasingly intrinsic sphere of everyday life, such liminal spaces offer a valuable vehicle through which to conduct postdigital LL research in situations where the physical field is inaccessible. As our research reveals, SNPs like WeChat can indeed allow researchers to build liminal LLs in-between, which cut across physical boundaries in times of crisis and limitation.

Local places came to life for participants in our WeChat group over time, through mundane encounters shared across borders, time zones and languages. As we reflect on the challenges of inviting new ways of seeing between strangers, we also gain a greater understanding of the risks, biases, and assumptions underlying shared content. The dialogues which emerged from the postdigital traces exchanged in our WeChat group illustrate how our ways of ‘seeing’ the spaces of ourselves and those of others are framed in relation to the social, economic, and cultural contexts from which they emerge. Like the social space animated in the exchanged photos, a postdigital ethnographic approach for engaging LLs without physical co-location must continually evolve according to these dynamics.

Acknowledgments

This work was produced in association with the ‘Urban Rural Assembly’ project (URA,01LE1804A-D), which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of the FONA programme ‘Sustainable Development of Urban Regions’ (NUR). The authors were employed at Technische Universität Berlin when the writing began, and would like to send their gratitude to the local collaborators of URA’s Living Labs across China and Germany who kindly shared their WeChat group experiences with the project.

References

-

Alibrandi, M., Thompson, A. & Hagevik, R. (2000). Documenting a culture. ArcNews 22 (3), 27.

-

Banks, M. (2018). Using visual data in qualitative research. doi:10.4135/9781526445933

-

Bengtsson, S. (2014). Faraway, so close! Proximity and distance in ethnography online. Media, Culture & Society 36 (6), 862–877. doi:10.1177/0163443714531195

-

Bluteau, J. M. (2019). Legitimising digital anthropology through immersive cohabitation: becoming an observing participant in a blended digital landscape. Ethnography 22 (2), 267–285. doi:10.1177/1466138119881165

-

Boellstorff, T. (2010). Coming of age in Second Life: an anthropologist explores the virtually human. Princeton University Press.

-

Boyd, D. M. & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: definition, history and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (1), 210–230. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

-

Braybrooke, K. (2019). Placeless’ making? Reframing the power-geometries of digital platforms in China through tactical co-creation. In L. Bogers & L. Chiappini (Eds.), The critical makers reader: (un)learning technology (pp. 258–269). Institute of Networked Cultures.

-

Braybrooke, K. (2022). Creative commons, open access, free/libre open-source software. doi:10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea2486

-

Camburn, B. & Wood, K. (2018). Principles of maker and DIY fabrication: enabling design prototypes at low cost. Design Studies 58, 63–88. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2018.04.002

-

Catlow, R. & Garrett, M. (2019). DIWO to DAOWO: rehashing proprietorial dominance of art practice. In V. Bradbury & S. O’Hara (Eds.), Art Hack Practice: critical intersections of art, innovation and the maker movement (pp. 40–51). doi:10.4324/9781351241212-5

-

Chen, S., Shao, B.-J. & Zhi, K.-Y. (2019). Examining the effects of passive WeChat use in China. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 35 (17), 1630–1644. doi:10.1080/10447318.2018.1559535

-

Chen, Y., Sherren, K., Smit, M. & Lee, K. Y. (2021). Using social media images as data in social science research. New Media & Society 25 (4), 849–871. doi:10.1177/14614448211038761

-

De Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Translation by S. Rendall. University of California Press.

-

Dodge, M., Kitchin, R. & Zook, M. (2009). How does software make space? Exploring some geographical dimensions of pervasive computing and software studies. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41 (6), 1283–1293. doi:10.1068/a42133

-

Finn, J. M. (2012). Visual communication and culture: images in action. Oxford University Press.

-

Franz, Y., Tausz, K. & Thiel, S.-K. (2015). Contextuality and co-creation matter: a qualitative case study comparison of living lab concepts in urban research. Technology Innovation Management Review 5 (12), 48–55. doi:10.22215/timreview/952

-

Higgins, A. & Klein, S. (2011). Introduction to the living lab approach. In Accelerating global supply chains with IT-innovation (pp. 31–36). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-15669-4_2

-

Jurgenson, N. (2019). The social photo: on photography and social media. Verso Books.

-

Kato, F. (2014). Learning with mobile phones. In G. Goggin & L. Hjorth (Eds.), The Routledge companion to mobile media (pp. 183–195). doi:10.4324/9780203434833.ch21

-

Kera, D. (2012). NanoŠmano lab in Ljubljana: disruptive prototypes and experimental governance of nanotechnologies in the hackerspaces. JCOM 11 (04), C03. doi:10.22323/2.11040303

-

Kong, T. M., Kellner, K., Austin, D. E., Els, Y. & Orr, B. J. (2015). Enhancing participatory evaluation of land management through photo elicitation and photovoice. Society & Natural Resources 28 (2), 212–229. doi:10.1080/08941920.2014.941448

-

Kozinets, R. V. (2010). Netnography: doing ethnographic research online. Sage Publications.

-

Kwan, M.-P. (2002). Feminist visualization: re-envisioning GIS as a method in feminist geographic research. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 92 (4), 645–661. doi:10.1111/1467-8306.00309

-

Laborgne, P., Ekille, E., Wendel, J., Pierce, A., Heyder, M., Suchomska, J., … Goszczynski, W. (2021). Urban living labs: how to enable inclusive transdisciplinary research? Urban Transformations 3 (1), 1–18. doi:10.1186/s42854-021-00026-0

-

Laws, G. (1997). Women’s life courses, spatial mobility and state policies. In Thresholds in feminist geography: difference, methodology, representation (pp. 47–64). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

-

Massey, D. (1993). Power-geometry and a progressive sense of place. In J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam & L. Tickner (Eds.), Mapping the futures: local cultures, global change (pp. 59–69). Routledge.

-

Meenar, M. R. & Mandarano, L. A. (2021). Using photovoice and emotional maps to understand transitional urban neighborhoods. Cities 118, 103353. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2021.103353

-

Møller, K. & Robards, B. (2019). Walking through, going along and scrolling back: ephemeral mobilities in digital ethnography. Nordicom Review 40 (s1), 95–109. doi:10.2478/nor-2019-0016

-

Nam, B. H., Weber, H.-J. L., Liu, Y. & English, A. S. (2022). The ‘myth of zero-COVID’ nation: a digital ethnography of expats’ survival amid Shanghai lockdown during the Omicron variant outbreak. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (15), 9047. doi:10.3390/ijerph19159047

-

Nykiforuk, C. I. J., Vallianatos, H. & Nieuwendyk, L. M. (2011). Photovoice as a method for revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 10 (2), 103–124. doi:10.1177/160940691101000201

-

Qian, Y. & Mao, Y. (2021). Coping with cultural differences in healthcare: Chinese immigrant mothers’ health information sharing via WeChat. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 84, 315–324. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.05.001

-

Robust (2021). Rural urban Europe. Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://rural-urban.eu/

-

Ruijsink, S. & Smith, A. (2016). European Network of Living Labs (ENoLL) [Transformative social innovation theory]. Retrieved November 29, 2022, from http://www.transitsocialinnovation.eu/resource-hub/european-network-of-living-labs

-

Stachowski, J. (2020). Positioning in ‘relational claustrophobia’ — ethical reflections on researching small international migrant communities in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies 78, 176–184. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.001

-

Statista (2022). WeChat — statistics and facts. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/topics/9085/wechat/

-

Steen, K. & van Bueren, E. (2017). Urban living labs: a living lab way of working. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions.

-

Sturken, M. & Cartwright, L. (2019). Practices of looking: an introduction to visual culture (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

-

Sun, W. & Yu, H. (2020). WeChatting the Australian election: mandarin-speaking migrants and the teaching of new citizenship practices. Social Media + Society 6 (1). doi:10.1177/2056305120903441

-

Sutton-Brown, C. A. (2014). Photovoice: a methodological guide. Photography and Culture 7 (2), 169–185. doi:10.2752/175145214x13999922103165

-

Tianyang (2022). WeChat group account. Retrieved November 27, 2022, from https://www.uhqq.com/fahang/22756.html

-

Wang, C. & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: concept, methodology and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior 24 (3), 369–387. doi:10.1177/109019819702400309

-

Wang, D. & Liu, S. (2021). Doing ethnography on social media: a methodological reflection on the study of online groups in China. Qualitative Inquiry 27 (8-9), 977–987. doi:10.1177/10778004211014610

-

Xiang, B. (2005). Transcending boundaries. Zhejiangcun: the story of a migrant village in Beijing. doi:10.1163/9789047406792

-

Zani, B. (2021). Shall WeChat? Switching between online and offline ethnography. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 152 (1), 52–75. doi:10.1177/07591063211040229

-

Zhou, Y. & Xiang, Y. (2021). Dual anxieties of technology and labour: an ethnographic analysis of a university’s WeChat groups in China. The Political Economy of Communication 8 (2), 56–74. Retrieved from https://www.polecom.org/index.php/polecom/article/view/124/351

Authors

Kit Braybrooke. Anthropologist and artist-designer whose work explores regenerative

futures at the intersection of digital, material and ecological spaces. Senior Researcher

with Urban-Rural Assembly at Habitat Unit, Technische Universität Berlin, and

Director of Studio We & Us, a creative lab which brings artists and communities

together across Europe, Canada and Asia to explore critical dynamics of the

Anthropocene, and celebrate more-than-human possibilities for systems change.

Webpage: https://drkitkat.com/.

@dr___kitkat @TUBerlin E-mail: krill.xiu@gmail.com

Gaoli Xiao. Research assistant at the China Centre (CCST), TU Berlin. Gaoli holds a

double M.Sc. degree in Urban Development and Urban Planning. She is interested in

themes such as migration, land politics, and socio-spatial inequalities. Her current

research explores the drivers of labour migration to small towns and rural areas in the

Yangtze River Delta.

E-mail: gaoli.xiao@tu-berlin.de

Ava Lynam. Researcher at China Center (CCST) and PhD candidate at Habitat Unit,

TU Berlin, focusing on migration, urban sociology, and socio-spatial inequality within

Chinese rural-urban transformation. She has a particular interest in the influence of

Chinese industrial projects in rural Southeast Asia. Ava is also a freelance editor,

writer, and ‘researcher in residence’ at urban design and architecture practice

Metropolitan Workshop. She previously worked between London and Dublin

as an urban designer on urban strategy, housing, and community engagement

projects.

E-mail: avarlynam@gmail.com