1 Introduction

A substantial body of literature in Public Engagement with Science (PES) argues for the need for greater connectivity between theory and practice [Baram-Tsabari et al., 2020 ; Metcalfe, 2019 ]. This gap has been described as ‘a deficit of the science communication domain itself’ [Sanden and Meijman, 2012 , p. 1]. There are also frequent calls for engagement to be integrated within the research process, and for scientists to think more reflexively about the role of their research in society [Mejlgaard, 2018 ; Salmon, Priestley and Goven, 2017 ]. However, such thinking does not automatically transform itself into practice and, as Salmon, Priestley and Goven [ 2017 ] have argued, there is a need for translation of PES theory into actionable, practice-able ideas for scientists and science communicators. This paper presents an endeavour to do this by using design 1 . to advance the application of PES theory within PES practice.

The opportunity was provided by Te Pūnaha Matatini (TPM), a Centre of Research Excellence for complex systems in Aotearoa New Zealand. In addition to carrying out scientific research focused on economic, ecological, and socio-ecological systems, investigators in this cross-institutional, multi-disciplinary research centre are highly committed to creating a research culture that values equity, diversity, indigenous knowledge and public engagement. In their roles as TPM investigators, authors Salmon and Bailey had been responding to a frustration articulated by Salmon, Priestley and Goven [ 2017 ], that PES literature ‘does not ‘speak for itself’ to scientists’ [Salmon, Priestley and Goven, 2017 , p. 62], that it can appear critical of science communication practice, and offers little practical guidance on how to do things differently.

Using a design lens (Bailey’s expertise), Bailey and Salmon had experimented — over a series of four engagement workshops — with a selection of tools, including an ‘engagement wheel’ conceptualised by Salmon and Roop [ 2019 ]. This was developed and iterated after each use. Other exercises included drawing and mapping the participants’ engagement plans (people, places, activities etc) and speculative cardboard prototyping that challenged participants to construct ‘magic’ devices to aid their science communication, 2 as a way to encourage lateral, reflexive thinking about challenges and routes to solutions (Figure 1 ). 3 In addition, Bailey had been experimenting with a ‘cardboard laundromat’ installation format at a series of conferences (science, STS, science communication and a design forum) as a designed space to engender reflexive participation and dialogue.

Off the back of these events, Salmon and Bailey developed a concept for an intervention that would aid scientists in developing their public engagement ideas. TPM funded a pilot of this ‘Engagement Incubator’ that could be applied at different stages of the scientists’ research projects. Horst’s intersection of STS and design in her installation-based work [Horst, 2011 ; Horst, 2021 ] had informed Bailey’s practice, and Horst was invited to join the EI as an observer and ‘critical friend’ [Burchell, 2009 ; Fook, 2015 ] to further interrogate and develop the EI through a PES and STS lens.

Within the supporting framework of TPM, the Engagement Incubator (EI) was developed to combine the following objectives:

- To embed ideas from PES theory throughout scientific research projects within TPM and to use these ideas to improve the projects’ capacity for successful public engagement

- To engage with scientific researchers about PES theory and practice in order to investigate how PES insights can best be made actionable and practice-able .

Using a distinction made by Irwin, the former objective can be understood as a form of ‘second-order thinking’ focused on creating dialogue and transparency [Irwin, 2014 , p. 160] and aimed at increasing scientist-communicators’ 4 reflexivity on how they engage with publics. Similarly, the latter objective can be seen as a form of ‘third-order thinking’ which questions ‘the operating assumptions and modes of thought on which individual initiatives depend’ [Irwin, 2014 , p. 167] and is here aimed at increasing our own reflexivity (as PES and science communication scholars) about how we engage with scientists.

To achieve both these objectives, we used design theory and practice for translating PES theory and to organise the materiality and sociality of the EI event. The strength of design methods in this context was to translate abstract concepts and theories into actionable ideas and tools, in a way that made them practice-able . By this concept we do not mean simply to provide science communication skills training, but that participants have absorbed and incorporated theoretical ideas from PES into their own practice, such that they reflexively shape this practice, whatever that may be. An important part of making PES theories practice-able is therefore to stimulate reflexivity within the individual participants (scientist-communicators and research facilitators).

On this basis, the overarching research question of this paper is to investigate how can we use design practice to reflexively advance the application of PES theory in PES practice? Importantly, reflexivity here applies to all the participants in the EI, including ourselves. This paper will therefore discuss both objectives mentioned above as well as interrogate the impacts and potential of our use of design.

In what follows, we first present our conceptual framework that proposes the application of design to facilitate a bridge between PES theory and practice. This is followed by a brief methodology section prior to three empirical sections, which provide an in-depth description of the EI as well as the participants’ reactions to it and our own reflections. To a certain extent, the material design and realisation of the EI as ‘event’ [Horst and Michael, 2011 ] is a large part of the answer to our research question, so in the final discussion, we examine three important points of learning that grew out of our reflections on the entire endeavour.

2 Using design in PES

Design’s relationship with PES is most frequently understood in the visual communication context — clarifying, illustrating [Trumbo, 1999 , p. 421]; as a translator of information with ‘the potential to increase the attractiveness, understandability, and communication power of research findings’ [Khoury et al., 2019 ]. But design as a discipline has broader applicability for PES. At the speculative end of the spectrum, it can also be deployed as an affective medium, ‘challenging hegemonies and dominant ideologies in contexts of science and technology, social inequality, and unchallenged disciplinary norms’ [Malpass, 2017 , p. 6].

In developing the EI, we picked from across the gamut of design approaches for specific interventions and activities, but part of design’s value in this context also comes from certain facets inherent to its processes. Design is a ‘third culture’ [Cross, 1982 ], with norms and preconceptions different to science and humanities. This different alignment gives an alternative perspective, which can ‘foster dialogue [and] lead to the development of complementary as well as divergent understandings of a study situation’[Cohen and Crabtree, 2006 ]. Providing this third perspective, outside of the norms of either science or PES, was a critical goal of the EI.

Mike Michael observes how designers tend to directly encourage ‘overspilling’ of the empirical, analytic, or political framing with regards to their engagement activities in a way that social science does not [Michael, 2012 , p. 529]. Designers are less preoccupied with generating data that can be accommodated and analysed within specific conceptual frames, and more open to amorphous and ambiguous exercises. Michael contrasts this with engagement through an STS/PES lens, which tends to be ‘linearly arrayed’ across ‘a closed arc of events’: problem identification, public and expert recruitment, engagement event, analysis, dissemination [Michael, 2012 , p. 543]. We deliberately employed what Michael [ 2012 , p. 543] calls a ‘processually open’ approach to our research methodology.

This flexibility aligns with another facet of a ‘designerly way of knowing’ [Cross, 1982 ; Cross, 2001 ]: design’s ‘reliance on generating fairly quickly a satisfactory solution, rather than on any prolonged analysis of the problem’ [Cross, 1982 , p. 224] — or at least not ‘analysis’ as it might be recognised in other domains. Getting to a ‘satisfactory solution’ relies on iterative development and incremental improvement of what already exists or is known, and is rooted in understanding and designing for human needs. This human-centred design approach 5 places emphasis on building empathy with users, and has a mindset of rapid prototyping to generate momentum and maximise opportunities to test and refine. These were key elements in our approach to designing the EI, and also qualities we wanted the participants to absorb.

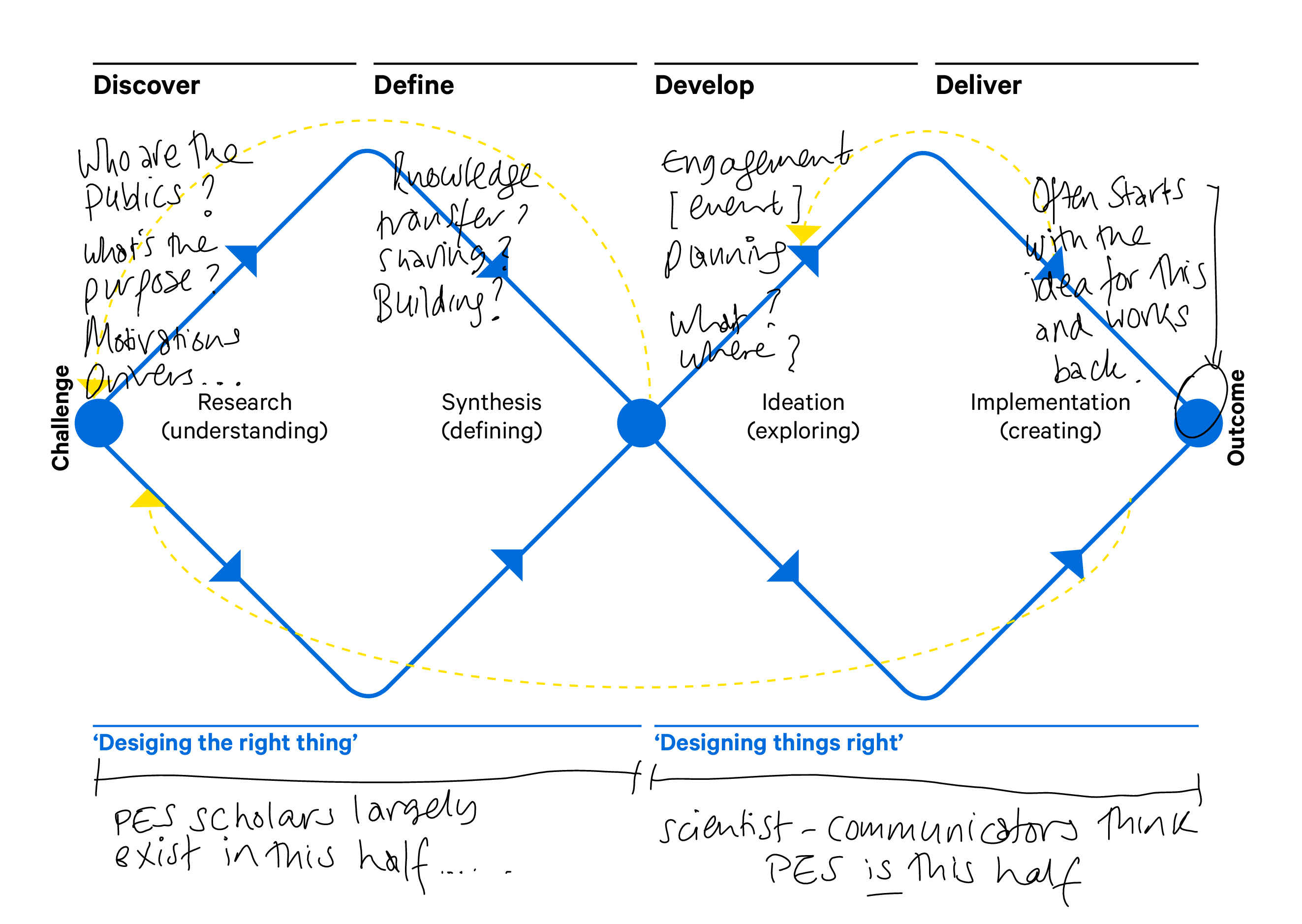

One of the most recognised visual representations of the design process is the UK Design Council’s ‘Double Diamond’ [Design Council, n.d. ] (Figure 2 ). It was released in 2004, building on models dating back to the 1960s, and was foremost a way of categorising, describing and codifying the design process (reflecting the way designers tend to work). Subsequently, it has been used as a method for considering the type, shape, structure and process of a design project.

The Double Diamond follows a four-step process structured as two diamonds of divergent and convergent thinking. The first diamond includes ‘Discover’ and ‘Define’, which entail breaking down assumptions about a problem to understand it from the position of affected people, and redefining the problem based on this insight. The second diamond includes ‘Develop’ and ‘Deliver’, which entail divergent consideration of potential responses to the problem, and the testing, rejecting or refining of possible solutions. The first diamond is about working out what ‘designing the right thing’ might be, and the second is about ‘designing the thing right’ [Ball, 2019 ].

We propose that part of the apparent lack of alignment between theory and practice in PES can be attributed to PES researchers tending to ask questions that sit naturally in the first diamond (what is the purpose of this activity; who are the publics?), whereas scientist-communicators tend to launch straight into the second diamond of ‘making and doing’ often with a predetermined outcome in mind. Taking a Double Diamond approach necessitates an entanglement of this default: scientist-communicators are made to first consider the context and purpose of their activities, and we (as PES researchers) are made to experience some of the discomforts and logistical challenges associated with delivering public engagement in practice. This requires employing what Horst [ 2013b ] describes as ‘a particular ethos … an appreciation of the value of discomfort’ which she considers necessary for such experiments to succeed Horst [ 2013b , p. 23].

A further design trait that we sought to deploy in PES practice comes from its propensity to be iterative. Though the Double Diamond’s simple representation suggests a linear process from problem to conclusion, implicit within the model is a recognition that testing and prototyping might be applicable at any stage, and at any point it might be necessary to ‘loop back’. At a macro level, design is never ‘finished’, but also, as Bruno Latour [ 2008 ] points out, it never starts from a blank slate either, it is always redesign: ‘There is always something that exists first as a given, as an issue, as a problem. Design is a task that follows to make that something more lively, more commercial, more usable, more user’s [sic] friendly, more acceptable, more sustainable, and so on’ [Latour, 2008 , p. 5]. So this cyclical redesigning is baked into the design mindset and aligns well with our goal for the EI to stimulate a reflexive approach to engagement design.

We use the term reflexivity in the sense of actively bringing to the fore assumptions about research and engagement and its impact on others (audiences, participants, publics). These are shaped by personal values and those of communities, society, or organisational power structures. Cunliffe [ 2016 , p. 741] describes this as ‘questioning what we, and others, might be taking for granted — what is being said and not said — and examining the impact this has or might have’. Beyond this though, we also recognise that reflexivity is not just the thinking, ‘but rather a type of thinking tied to action’ that enables ‘ways of acting that would not otherwise be possible’ [Salmon, Priestley and Goven, 2017 , p. 58]. In essence, reflexivity needs to be enacted, and the reflexive participant ends up changed as a result of putting this thinking into practice.

In what follows, we first describe the background, methods and methodology of our experiment with the EI and our efforts to learn from the process. We subsequently describe the EI in more detail and provide examples of how we sought to put the principles of design into practice.

3 Background and methodology

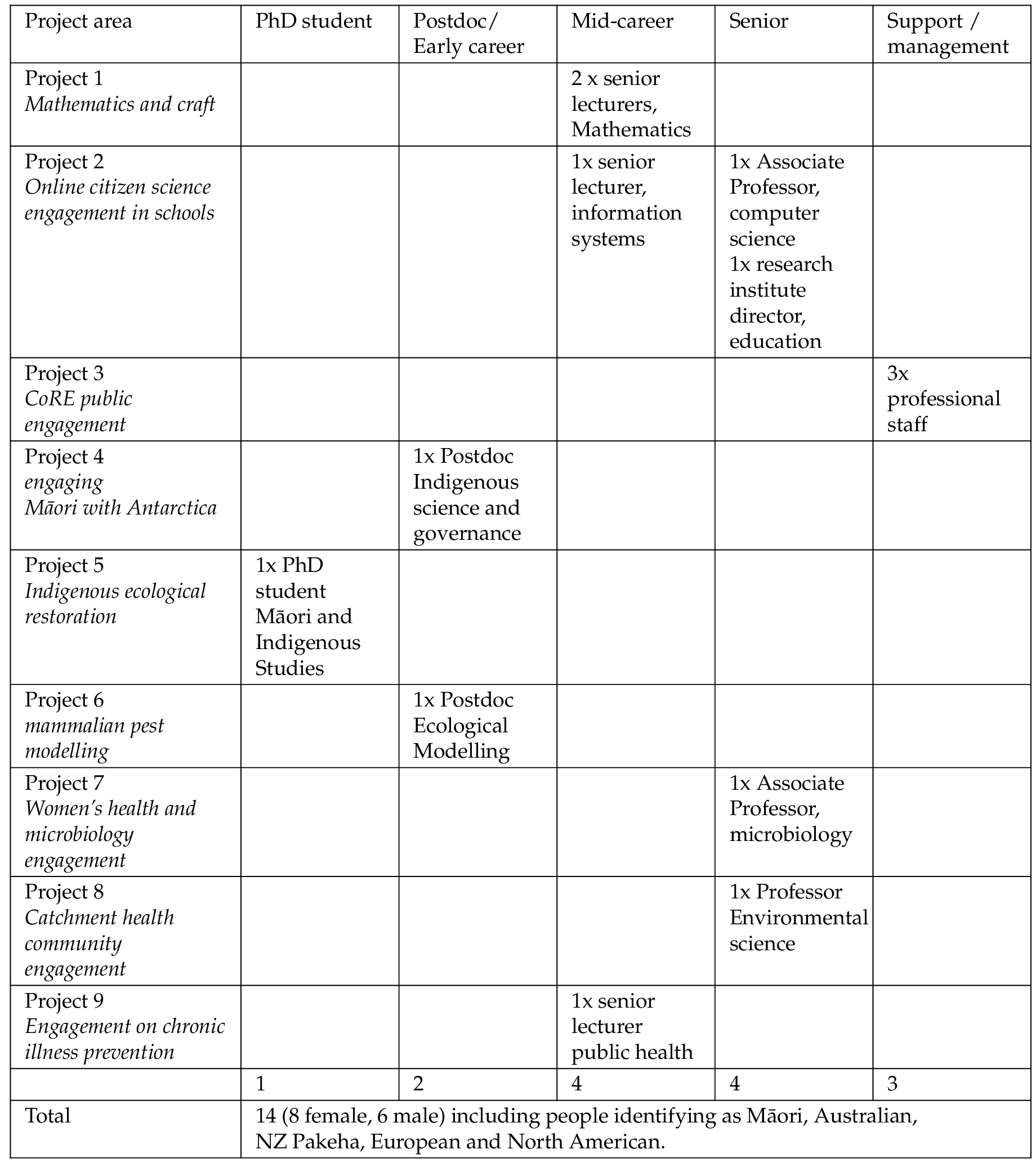

The EI occurred in February 2020 and involved 14 participants. They represented nine different research projects that spanned a wide range of scientific fields and seniority, from PhD student to Professor (see appendix A ). There were 8 female and 6 male participants, including people identifying as Māori, Australian, Pākeha [New Zealander of non-Māori descent], European and North American. They also represented a wide range of experience with public-facing engagement. The workshop participants also included the authors in roles as a primary facilitator, a facilitator/designer and an observer.

The science communication projects being workshopped were diverse. Examples include: hands-on experiences of mathematical principles, knowledge of disease prevention, citizen science, and giving voice to indigenous people in policy processes. We did not try to make distinctions between forms of engagement, for instance valorising a focus on dialogue or political empowerment, but rather accepted at face value what the researchers themselves saw as meaningful communication and engagement. 6

Although it was optional, all participants consented to their data being collected through a pre-event survey, observation throughout the event, and follow-up surveys or interviews. Information provided in the pre-event survey, for example about the nature of their project and what they wanted to gain from the experience, was used to inform the design of the EI.

Participants’ travel, catering and accommodation was organised for them. This helped to contribute to a sense of being cared for, and valuing their contribution. The agenda allowed the participants to unwind and enter the EI space mentally as well as physically. Participants shared their engagement ideas on the first evening, prior to an introduction to PES theory (in what we called ‘SciComm 101’) the following morning. This lay the groundwork for an exploration of their assumptions and understanding of engagement. This was followed by a full day unpacking, interrogating and workshopping their projects in some depth, based on the ‘pop-up laundromat’ theme (described below), and a final morning of reflection and project planning.

In the final session, participants noted down memorable moments, ‘a-ha’ moments, or other reflections they might like to share about the experience and then we conducted a focus group style discussion. We fully acknowledge that this feedback was likely influenced by social desirability bias [Grimm, 2010 ], and present it with this caveat. The process of collective reflection was not purely for our data-collecting purposes, for which we might have adopted a more anonymous and systematic method. Rather, its main purposes were to (a) encourage self-reflection amongst participants in order to contribute to an on-going reflexive process, and (b) to deepen our own understanding of the lived-experience of participants.

We also recorded field notes and observations throughout the design and delivery of the event, supported by photos, video and sound recordings. A few months after the EI, participants were contacted for follow-up interviews but the Covid pandemic (which emerged soon after) meant that only one was in a ‘mental space’ to be able to reflect on the event. In addition, all the science communication projects were either postponed or changed significantly.

Data from the pre-EI survey, recordings of discussions and interviews, and email feedback were collated and (where applicable) transcribed, and then inductively coded into themes in an iterative process guided by Braun and Clarke’s ‘reflexive thematic analysis’ approach [Braun and Clarke, 2013 ; Braun and Clarke, 2019 ]. This ‘fluid and recursive’ [Braun and Clarke, 2019 , p. 591] interpretive analysis was designed to help us understand how the EI supported reflexivity. As we assume reflexivity to be a foundational human activity [Lynch, 2000 ], it did not make sense to ask whether the EI created reflexivity but rather how it shaped such reflections, in order to tease out instances where we could intersubjectively discuss their meaning.

On this basis, the following empirical analysis falls in three sections. Section “Designing the Engagement Incubator” describes the design of the EI based on Bailey’s archive, reflections and logbooks from the process. Section “Translating PES theory in the Engagement Incubator” demonstrates how the EI translated aspects of PES theory and how workshop participants reacted to this. Finally, section “Participant reflections on the Engagement Incubator” discusses how participants reacted to the entire experience and points to how reflexivity was supported and shaped through the EI.

4 Designing the Engagement Incubator

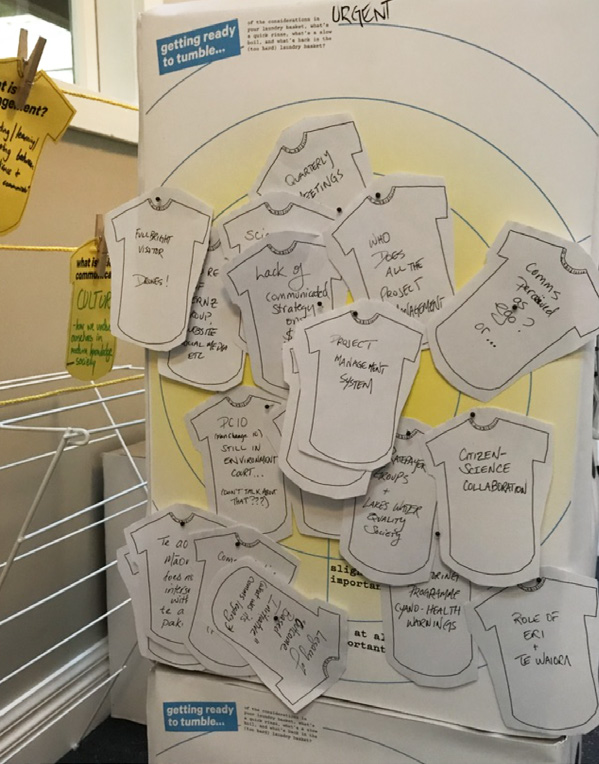

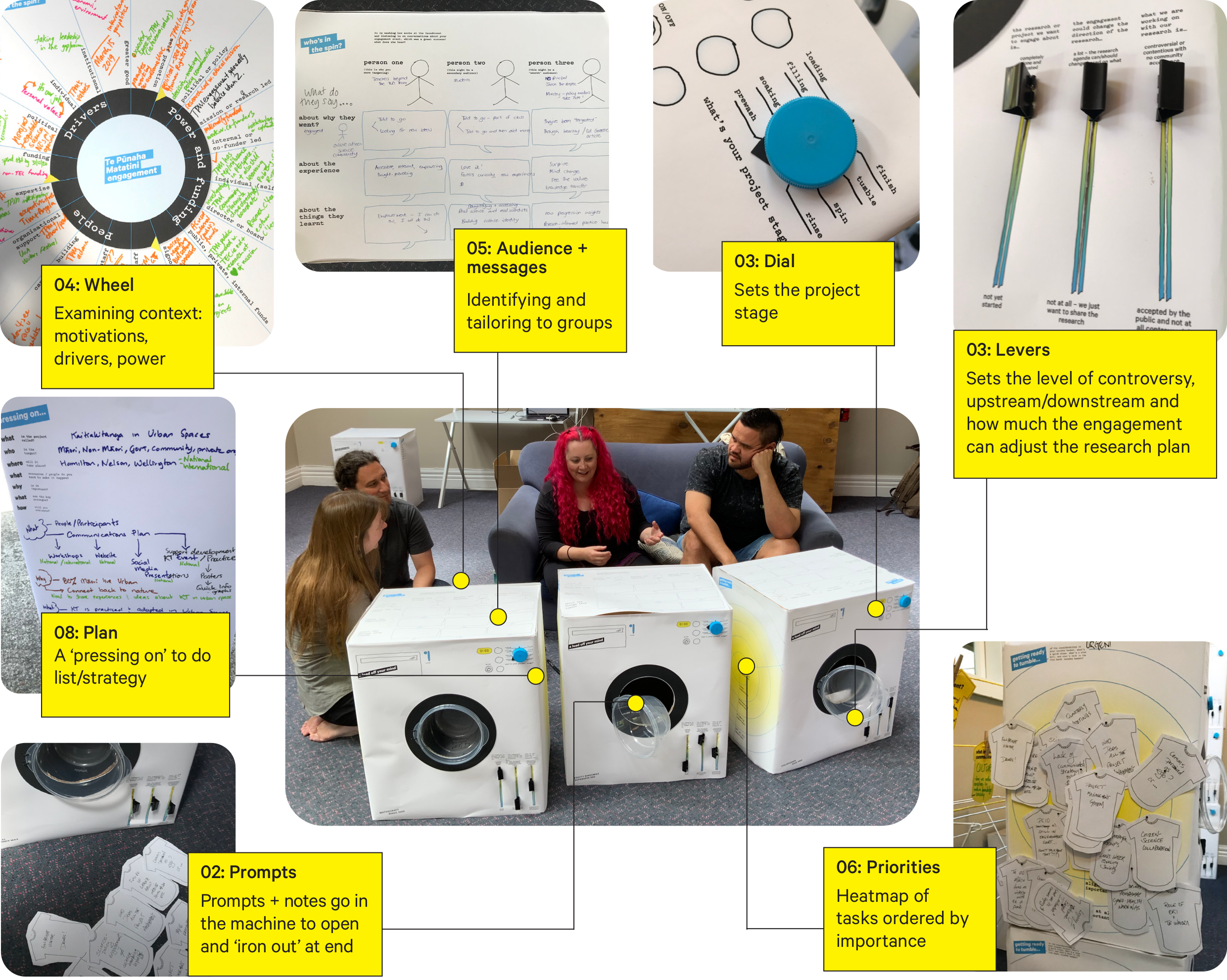

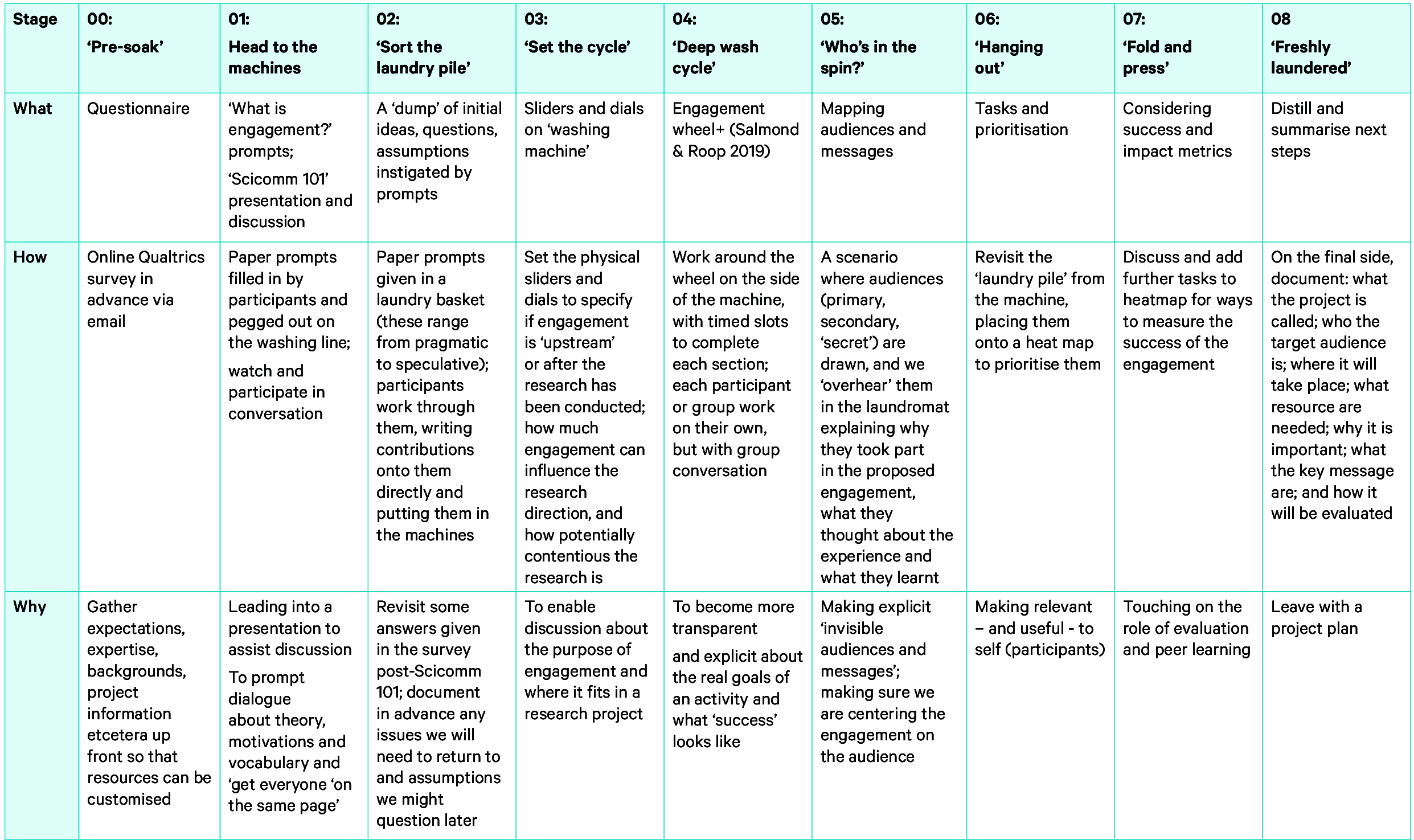

The central theme of the EI was the ‘pop-up laundromat’ (Figure 3 ), which built on an installation at a series of conferences that was developed by Bailey (Figure 1 ). This designed installation played with metaphors that connected washing and reflexivity (rinsing and wringing, hanging out, agitating, ironing out, pressing on…). It also activated participants using ‘design probe’ inspired prompts [Boucher et al., 2018 ; Mattelmäki, 2005 ; Wallace et al., 2013 ]. These prompts were provocation questions printed on paper in the shape of garments, which participants could write on, then ‘peg out to air’ publicly, or put in the machines to ‘wash’ anonymously, encouraging both individual reflection and collective dialogue. Drawing on Hächler’s [ 2015 ] methods of ‘social scenography’, visual, material and spatial design were used to encourage participation, self-questioning and dialogue, with the aim of transforming the ‘visitor-observer’ into ‘visitor-participant’ [Hächler, 2015 , p. 366].

At the EI, each project was given a ‘washing machine’ as the canvas for workshop activities. These were personalised, so it was clear everyone had their own ‘work-load’ or project space. The material and visual quality of the set-up, though low-fidelity and low-tech, was highly deliberate. Prop elements such as uncovered ironing boards suggested ‘wireframes’ or a work in progress; iteration baked into aesthetic. Repurposed elements such as bottle top ‘knobs’ and plastic bowl ‘doors’ pointed to a DIY, unpretentious approach. Cardboard and paper were the primary materials. These are cheap, familiar, and don’t require careful handling: they can be written on or have pins stuck in them without concern you are ‘ruining’ them. The cardboard ‘washing machines’ were augmented with hand-drawn elements, drawing attention to the presence of a maker. The fact that the washing machines were clearly constructed by hand also acted as part of the narrative: each inconsistency showed the mark of a human. Together, these marks suggested an authenticity — vulnerability even — that, alongside the humble materials, connote that the laundromat is a place where it is ok to be human; ok to be imperfect, ok to leave a trace of a process.

Field note excerpts: Horst

Bailey has created ‘washing machines’ by gluing luxurious white paper with print on big cardboard boxes and adding plastic levers and a ‘door’. There is a washing machine for each research project and she has personalised the front with a title for the machine that is a pun on the specific research project. The other four sides of the machine have a headline, a couple of questions and nicely designed spaces to be written on by the researchers as they go through the phases of planning the public engagement of their research project. As an invited guest I don’t have a machine and I feel slightly envious. The thick white paper on the machines is very inviting and so are questions like: what is your secret audience? I lean back in the comfortable sofa and breathe in the buzzing small-talk, the hum of concentration and collegial goodwill as well as the sounds of friendly nature outside the open doors. Our workshop is both very tangible and material with the writing on washing machines and simultaneously very abstract with its focus on future possible engagements and objectives. In my slightly other-worldly state of jetlag I enjoy how Salmon convenes the process with an expert balance between moving on and listening to input, allowing individuals to be who they are, but also creating a collective sense of shared purpose. It is pleasurable, but also highly demanding as a large number of reflections on public engagement seem to struggle for my attention.

The laundromat metaphors and puns brought a degree of levity and playfulness and became a way to talk about the activities as a process as shown in Figure 4 . As well as serving as a prop for various phases of the workshop, the washing machines gave us a great metaphor for thinking about public engagement as a cyclical household chore, which we were undertaking in the simultaneously public and intimate space of a ‘laundromat’. Interestingly, we discovered the notion of repetitively, cyclically, doing laundry to be not only a helpful and accessible image for the EI, but also a powerful metaphor that gave new meaning to our own understanding of public engagement. We will return to this in the discussion.

The washing machines — and associated tools such as written prompts — functioned as a canvas and toolkit or guide to lead the participants through the ‘cycle’ of structured, purposeful tasks (Figure 4 ). It also enabled accretion of documentation during the course of the EI. Using a structured toolkit has been identified as an approach that is non-threatening and hence easy to sustain [Taffe, 2018 , p. 354]. The process was intentionally designed such that conversation could flow while hands captured salient points on the prompts or directly onto the machines.

5 Translating PES theory in the Engagement Incubator

Every stage of the laundromat cycle was designed to respond to and translate a specific aspect of PES theory. In this section we look in more depth at steps 3, 4 and 5: ‘set the cycle’ (Figure 4 , stage 03), ‘deep wash cycle’ (Figure 4 , stage 04) and ‘who’s in the spin?’ (Figure 4 , stage 05). These were each designed to translate some of the more nuanced aspects of PES theory that are often overlooked in more pragmatic science communication training programmes.

5.1 ‘Set the cycle’ sliders

The value of the literal ‘hands on’ experience of the washing machine was particularly evident in an early exercise to ‘set the cycle’ (Figure 4 , stage 03) through manipulating three ‘sliders’ on the front of the machine (made from foldback clips). These sliders asked about:

- the research project stage (as opposed to the engagement component), from ‘not yet started’ to ‘completely done and dusted’;

- the degree to which public engagement could change the direction of that research (from ‘not at all — we just want to share the research’ to ‘a lot — the research agenda can/should change based on what is learnt’), and;

- the degree of public acceptance of the research (from ‘controversial or contentious with no community acceptance’ to ‘accepted by the public and not at all controversial’).

These questions are deceptively simple, but they allow discussion of the possible roles of publics in research and engagement. They also challenged the participants to think about their preconceptions of the relationship between scientist and publics.

The first slider required a consideration of the potential for engagement as an ‘upstream’ activity [Rogers-Hayden and Pidgeon, 2007 ], which was a terminology that some participants were wholly unfamiliar with. Introduced in this context, however, it became clear that the first two levers are interdependent, something which seems self-evident but was observed with surprise by participants. The experience activates the terminology, and avoids it becoming exclusionary ‘social science speak’ [Chilvers, 2012 , p. 293]. The first two sliders also became a useful vehicle to discuss the participants’ actual situation (where engagement is often reactive) and what it might have been in a more ideal scenario, without becoming hamstrung by a sense they haven’t ‘done it right’. These are not binaries, and physically moving the sliders tacitly suggests we can move from one state to another by degrees.

The third slider is also deliberately simplistic, in that it uncritically asks about ‘the public’. This enabled a conversation about different publics [Michael, 1998 ], and how specific groups might place that slider in a different position (indeed, where different people in the room might place that slider). It also allows the idea of ‘social licence’ to be considered (acknowledging the problems with the term [Jenkins, 2018 ]), and with it issues such as ‘cultural licence’ [West et al., 2020 ], which have particular resonance to TPM’s focus on ‘indigenising science’. We observed participants recalibrating the sliders numerous times during the discussion, suggesting that their non-static nature assisted the conversation’s fluidity.

5.2 ‘Deep wash cycle’ wheel

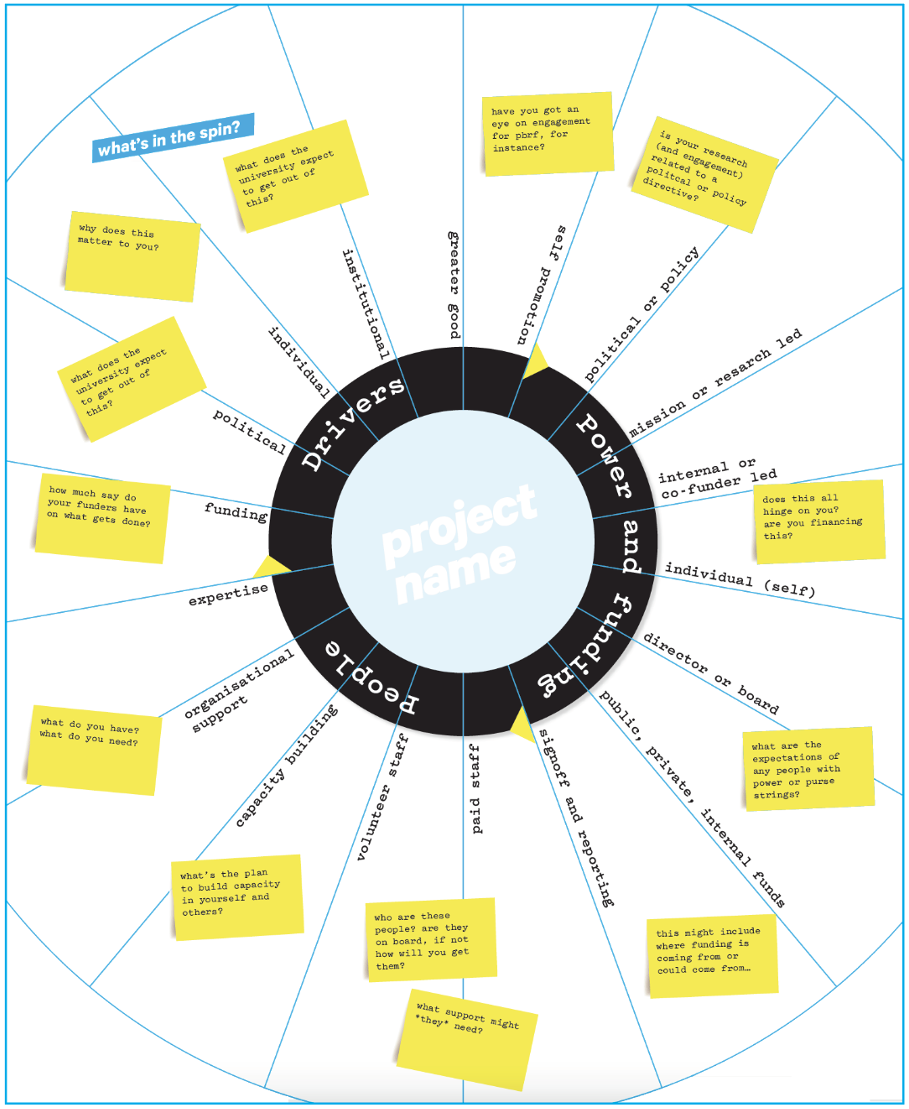

‘The wheel’ (Figure 4 , stage 04 and Figure 5 ) is the fourth phase of the cycle: an immersive ‘deep wash’. This was based on a tool devised by Salmon and Roop [ 2019 ] that Salmon and Bailey had iterated through prior workshops. During this stage, participants were asked to externalise considerations that might not normally be overtly declared (as well as more practical considerations) in order to become more transparent about the implicit as well as explicit goals of their activities.

This was a timed exercise to encourage rapid contribution under the headings ‘drivers’, ‘power and funding’ and ‘people’. After completing the wheel in less than 45 minutes, participants shared their insights with the wider group. This provided a foundation for a group discussion centred around ideas from PES related to the complexity and culture of engagement, motivations for engagement, implicit power structures and the roles that scientists play in engagement [Horst, 2013a ]. It also ‘forced’ participants to ‘unpack’ their projects prior to exploring audiences and messages (Figure 4 , stage 05). In our experience, this is often overlooked in traditional science communication training and reflects our intention to connect the two ‘diamonds’ as described previously (Figure 2 ).

5.3 ‘Who’s in the spin?’

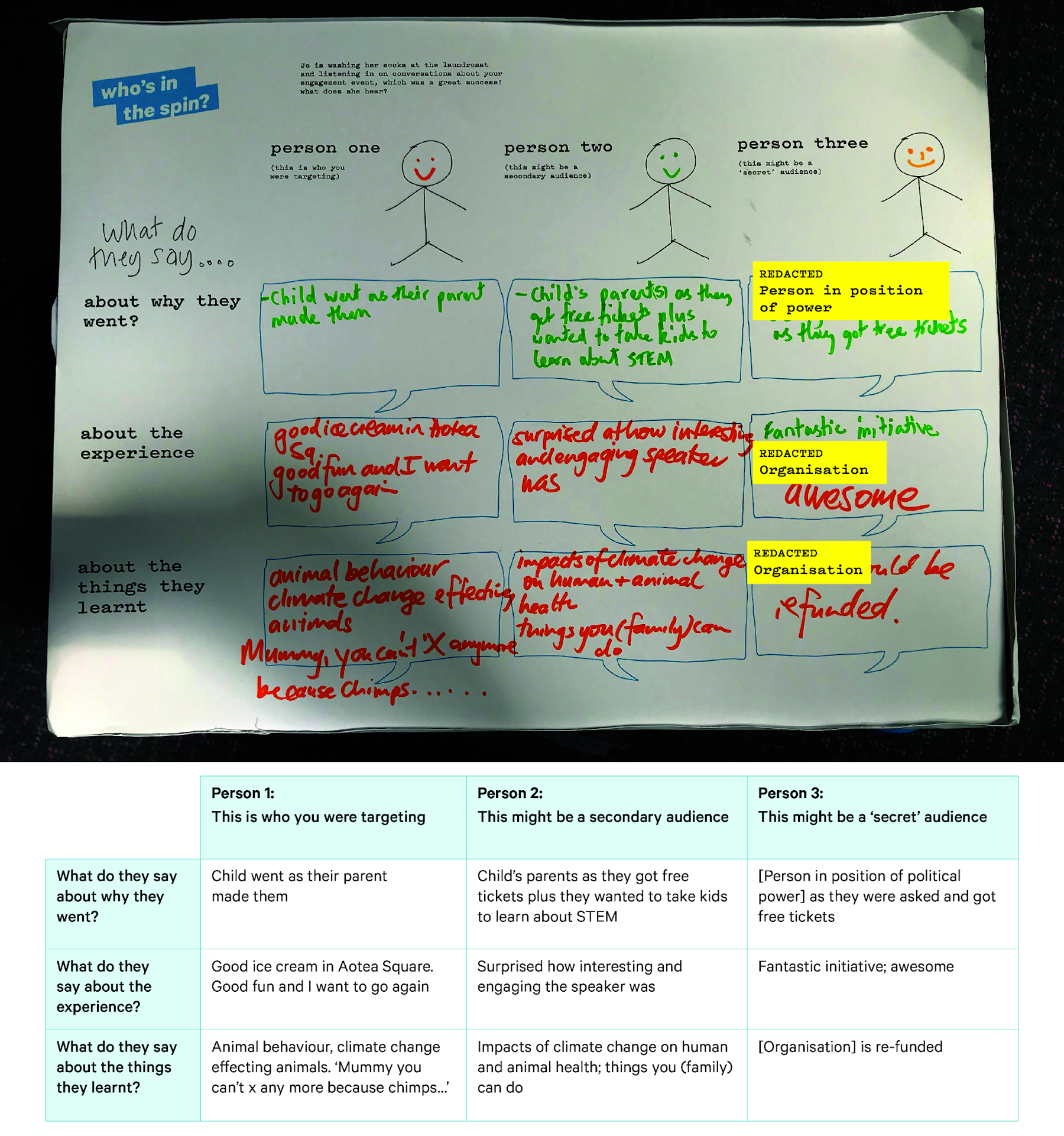

A regular feature of most science communication (including PES) training programmes is the identification of clear goals, audiences and messages [Stocklmayer, 2013 ]. While this might seem to be a fairly straightforward activity, we used this exercise to invite participants to reflect on the purpose(s) and (often multifaceted) objectives of the engagement [Besley, Dudo and Yuan, 2018 ; Horst, 2021 ]. We asked the participants to identify three desired audiences for their activity (Figure 6 ). This included a ‘secret audience’ (one they would not normally declare openly), such as a person in a position of power, a funder, an unsupportive colleague, or someone on a promotion committee.

After identifying audiences, participants were asked to consider what they (ideally) wanted each of these audiences to take out of the experience. Riffing off the theme of the installation, we presented this as a conversation that might be overheard in a laundromat (or similar private-public space) in which a personification of that audience shares their experience of the initiative. By asking why this theoretical person might attend, what they would experience and what they would learn, we attempted to tease out a range of audiences, messages, experiences and outcomes that would define ‘success’ for their activity.

6 Participant reflections on the Engagement Incubator

We have described above how we designed the EI to support participants’ reflexive development of their engagement. As mentioned in section “Background and methodology”, we also directly asked for participants’ reflections and feedback before, during and after the EI. In our own reflexive thematic analysis of this material, we identified three interrelated issues: 7 the value of design; collective social experience and culture; and resonant PES content, which we will consider in turn below.

The participants reported that the designed experience of ‘going to the laundromat’ created a sense that they were part of a well-planned and intentional process. We also observed that the structure generated a momentum to the process that appeared to keep energy and engagement up: ‘the washing machines make you feel like you’re part of a process, it didn’t feel ad hoc, it felt well thought out, so you feel like you can just trust the process’ [participant J].

We also observed a high degree of engagement with the tactile, physical elements, and a notable lack of people checking digital devices. One participant noted the way that even when outside concerns encroached upon being present: “[the] process kept pulling us back to a de-digitalised algorithm… The fact that there was this thing, it made it a physical process” [participant D]. Perhaps related to the fact that they ‘owned’ a tangible object, participants even asked if they could take their washing machines home; something we have never observed in a ‘flipcharts and Post-Its’ workshop context!

Feedback suggested that the designed experience itself created a richer experience than might have been attained had the same activities been carried out without the connecting laundromat theme. As one participant noted, “I think a cool point about the laundromat specifically is that the design component itself just creates a space and time — and a structure — the physical structure of the box is really good to work your way around. You could have just put all those words on one sheet of paper, but I doubt it would have had the same sort of effect.” [Participant B]. The playful element of the design was also important, and enabled an accessible route to conversations about PES concepts that are not always obviously relevant to practitioners.

Secondly, most of the participants reflected on the power of the group experience created by the EI, which was interesting to us as it wasn’t one of our initial design considerations. As one participant explained:

“I also got a lot out of the fact that it wasn’t just me and a washing machine on my own, it was a laundromat! …so there’s other people that you can interact with … the generosity of spirit with which everyone was sharing their experience was so great, and then having — you know — laundromat managers who are really experienced with laundry, …who could point out some of our blind spots, which was really great. And I think that I wouldn’t have seen some of those blind spots if it wasn’t for the group of people and for the guidance of experienced people.” [Participant K].

Peer interaction during the EI appeared to not only enable collective development of ideas but also contribute to a strong sense of social license with regard to prioritising and doing engagement. One participant explained, “I feel like I came with a really specific ‘yep this is what I want to do’ but that feedback from everybody has helped to really distil it… . And also the permission I’ve been given to ‘yes just go ahead and do it!’” [Participant A]. This was reiterated by several participants, for example: “the process has been permission-giving and affirming and really brought to the fore some of my own assumptions.” [Participant G]. This peer-affirmation also contributed to a sense of increased confidence: “I’m just more comfortable with it, and that’s enormously valuable. Instead of just running round in circles.” [Participant B].

In line with recent literature that proposes consideration of science communication as culture [Blue, 2019 ; Davies and Horst, 2016 ] the EI appeared to play a role in honouring and enacting shared cultural values, including bicultural values in Aotearoa New Zealand, the research culture of the TPM community, and the culture of science communication. For example, one participant described the shared cultural and physical experience: “we stepped into this whare [home] — which is the [laundromat] — in time and space and we’re coming out a little bit cleaner in our thoughts on engagement” [Participant B], another described it as “a safe space to air our dirty laundry.” [Participant A].

One participant noted “it was really valuable because it was clearly a TPM process ” [Participant D], suggesting that the EI created an opportunity to connect with and enact the values that the TPM community aspire to. Another commented on the value of the informal times, especially on one evening when: “…people were opening up, and there was a little bit of a rant session … it was kind of interesting to hear what people’s deeper issues were about funding, or anything we were dealing with. So that kind of fits in with the whole, I guess, rinsing out or tumbling…” [Participant F].

Thirdly, the EI process drew on many concepts from PES, including the relationship between science and publics, the role of the scientist, dialogue and coproduction, inherent power structures, the purpose of engagement, explicit and implicit audiences and messages and evaluation. While participants identified with various of these, the notion of the purpose of public engagement being about informing decision-making, or enabling democracy, was repeatedly referred to as being confronting or memorable as the following conversations demonstrate:

[Participant A] “My aha moment was distilling (or when it was for us distilled) — engagement — down to that one word: democracy. Despite the difficulties democracy as a word has (or as a concept).

[Facilitator] What was the aha-ness of it?

[Participant A] Oh, just that it was, that all the things that we were thinking about could be put in that ‘ah yes there is a very simple way to say that’…it’s the fact that it could be distilled down to that. Or justice… that actually underlying all of those things, all of those reasons why we do stuff, was a very simple concept.”

This is also illustrated by the following conversation between two participants in the same project:

[Participant J] “I really enjoyed hearing the word ‘democracy’. Because it’s central to [our project] and so we finally have a word to describe…

[Participant K] …Yeah I think we’ve even used words like democratic and citizenship and that sort of thing but we’ve never actually — we’ve danced around the word democracy, just —

[Participant J] …So when I saw that I thought “ah! Of course.” So that was awesome.”

This discussion of the notion of democracy is a good example of how the EI allowed participants to (re)discover ideas that are basic to a lot of PES literature, but might easily be overlooked in the day-to-day business of planning and executing science communication. We find it noteworthy that the participants who were most struck with this were some of the most experienced communicators in the group. This points to a continuous need for reflexivity as an interest in rediscovering basic purposes of ‘what we are busy doing’ [Horst and Michael, 2011 , p. 287] or what ‘we take for granted’ [Cunliffe, 2016 , p. 741].

7 Discussion

At the heart of our investigation was an exploration of the role that design can play in stimulating reflexivity about engagement among scientist communicators. Our three empirical sections have demonstrated how that happened in a number of different ways throughout the process. In this final discussion we explore three aspects of our own reflections that we believe are important. These are: (i) the role that design played in making PES theory practice-able, (ii) our roles as researchers enacting PES theory, and (iii) the circularity and need to continually revisit and re-imagine engagement work.

7.1 The role of design

We have noted previously that the EI laundromat space, objects and theme were highly deliberate. As a visual communication designer, this is Bailey’s ‘bread-and-butter’ practice so the fact that an experience carefully designed to be fit-for-purpose worked for that purpose is unsurprising. However, through our own critical reflection it became clear that the value of the designed experience was not only in the products and tools (outputs, artefacts, exercises, environment), but also in the iterative process of design. However, in the EI, these two facets of design are entangled: the products help produce the conditions that enable the process . In essence, design shapes the experience, and the experience shapes the participants to think like designers, which can open opportunities for consideration of new modes of engagement. Design can be both connective and generative of theory and practice.

Central to a design approach is an expectation that development happens through discovery, synthesised into an idea that can then be evolved, tested and refined cyclically. Planning and developing the EI, we moved through the stages of the Double Diamond (Figure 2 ), and were comfortable seeing the EI as a prototype. It was a low-fi iteration to try out, test and develop (with an expectation of further cycles). Hence, our participants were part of a coproduction exercise in relation to our research (made transparent through their participation in the university’s ethics process [HEC 025554]). In this sense, design and PES are intertwined. We designed a way to share and develop knowledge about coproduction through doing coproduced engagement and treating our learnings from that as part of a design cycle.

We deliberately and intentionally employed design to inform the way we were doing PES, and we also saw this reflected in our participants’ experiences. While we worked through the stages of the EI, it became clear to many participants that they had initially jumped to the second ‘diamond’ — they had not established what the ‘right thing’ would be for their audiences (or in some cases themselves), so they were not in a position to ‘ do the thing right’. Conversely, others started off feeling somewhat paralysed by aspirations regarding dialogue and coproduction and the need to ‘get it right’ from the get-go. As the laundromat reinforced a sense of quick rough-and-ready sketching and probing of ideas, rather than expecting things to be ‘polished and precious’ from the outset, it was okay to consider engagement a more recursive practice which allowed iterative improvement. Participant feedback suggested that knowing these steps were designed to be somewhat repetitive gave a sense of ‘safety’ that they could trust the process.

Despite having been involved in designing the process, Bailey especially reflected that the act of consciously ‘doing’ the process as an embedded researcher helped her enact theory at a much deeper level. She had previously felt there was a void between her recognising the theoretical importance of reflexivity and actively doing it. To be reflexive requires us to be vulnerable, personally and professionally; to be open to scrutiny within a group context even more so. That’s uncomfortable, or even to some degree risky. What the step-by-step process of the EI does is act as a rope to lower ourselves in with control, and, at a risk of mixing metaphors, it begins to illuminate the reflexive space we are occupying as we head into it.

7.2 Enacting PES theory

The design of the EI deliberately incorporated opportunities to highlight examples of knowledge transfer (e.g., the SciComm 101 presentation), dialogue (e.g., participation in the Wheel exercise), and coproduction (e.g., the entire process in which participants and researchers worked collaboratively to design an engagement project that could not have emerged without the input of all parties). As a way of demonstrating reflexivity, we unpacked our own explicit and implicit goals for the EI and shared this process with the participants. 8 In this way, rather than ‘telling them’ to be reflexive, we attempted to model reflexivity and, in so doing, made it practice-able for ourselves.

The entire experience therefore provided an opportunity for reflexive analysis and unpacking of the process, which is unlikely to have occurred if Bailey and Salmon had simply positioned themselves as facilitators. This was activated by inviting Horst to join as an observer and critical friend. That is to say, we were invested in gaining research insights relevant to PES as well as engagement planning outcomes for the participants, and being ‘embedded’ [Lewis and Russell, 2011 ] enabled this. The experience of enacting our own engagement during the EI, and subsequent analysis of this, therefore generated a rich experience that challenged and deepened our own understanding of, and relationship with, the field.

7.3 The circularity of engagement

Finally, we noted above that a reflexive process is one in which the participant emerges somehow different from who they were at the start. For us, as embedded researchers, our clearest insight was undoubtedly that of the circularity of engagement. This was prompted by the power of the metaphor of laundry, but the wider usefulness of this metaphor only dawned on us slowly. While we started with the notions of ‘airing dirty clothes’ and ‘taking a load off your mind’, the circularity of the act of washing began to take on a different meaning. Washing is repetitive work that needs to be done regularly: we do not wash our clothes so that they will never become dirty again. Rather, washing is a recurring part of daily life. We have developed machines, detergents and routines to make it less time-consuming and more effective, but the reproductive nature of washing is clear. 9

Based on Horst’s fieldnotes regarding the friendly, collective nature of the interactions within the EI (Figure 3 ), it became clear to us that the EI could also be perceived as a collective doing of reproductive household work. Public engagement, like washing, is not something academics can just do once and then walk away from, but rather it needs to keep being done , as part of maintaining and developing the relationship between science and society through changing times and cultures. This is also true of engagement about PES ideas. These are not concepts that can just be written up once, or taught, with an expectation that the ideas will be easily understood and adopted. Rather, they need to be re-considered, re-conceptualised, continually re-engaged with: re-designed (in the sense Latour [ 2008 ] uses the term).

The experience of the shared collaborative atmosphere at the EI also modelled the development of a culture of engagement, in which academics jointly take on responsibility for contributing to good science-society relations and also share with each other an important part of modern life as a researcher. However, it is important that the engagement was also culturally and temporally situated. We don’t for a moment suggest that readers now create pop-up laundromats around the globe — this particular installation was designed specifically and thoughtfully for a particular time, place, people and culture. Which brings us back to the need for thoughtful and deliberate design.

8 Conclusion

We have described and reflected on the opportunity for design to be used to help translate PES theory, and make it accessible to scientists. Via an iterative design process, a bespoke ‘cardboard laundromat’ environment, which incorporated a toolkit of exercises, was developed to help scientists workshop their own public engagement planning. In addition to this primary goal, the Engagement Incubator became an engagement activity about engagement: informed by PES theory and embedding the practice of doing it . Through reflexive thematic analysis of participant feedback and documentation, and our fieldnotes as embedded researchers, we demonstrate the potential for design to make PES theory practice-able; illuminate how our roles as researchers enacting PES theory deepened our own understanding of it; and point to the circularity and need to continually revisit and re-imagine engagement work. We hope this case study encourages PES researchers and practitioners to collaborate, acknowledge discomfort, and reflexively learn from each other’s experience and expertise.

Appendix A Participants and projects

References

-

Ball, J. (1st October 2019). ‘The Double Diamond: A universally accepted depiction of the design process’. Design Council . URL: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/double-diamond-universally-accepted-depiction-design-process .

-

Baram-Tsabari, A., Wolfson, O., Yosef, R., Chapnik, N., Brill, A. and Segev, E. (2020). ‘Jargon use in Public Understanding of Science papers over three decades’. Public Understanding of Science 29 (6), pp. 644–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662520940501 .

-

Bason, C. (2017). ‘The changing nature of design’. In: Leading public design. 1st ed. Bristol, U.K.: Bristol University Press, pp. 33–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t88xq5.7 .

-

Besley, J. C., Dudo, A. and Yuan, S. (2018). ‘Scientists’ views about communication objectives’. Public Understanding of Science 27 (6), pp. 708–730. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662517728478 .

-

Blue, G. (2019). ‘Science communication is culture: foregrounding ritual in the public communication of science’. Science Communication 41 (2), pp. 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547018816456 .

-

Boucher, A., Gaver, B., Kerridge, T., Michael, M., Ovalle, L., Plummer-Fernandez, M. and Wilkie, A. (2018). Energy Babble. U.K.: Mattering Press. https://doi.org/10.28938/9780995527720 .

-

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. 1st ed. London, U.K.: SAGE Publications Ltd. URL: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/successful-qualitative-research/book233059 .

-

— (2019). ‘Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis’. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4), pp. 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676x.2019.1628806 .

-

Burchell, K. (2009). ‘A helping hand or a servant discipline?’ Science, Technology & Innovation Studies 5, pp. 49–61. https://doi.org/10.17877/de290r-970 .

-

Chilvers, J. (2012). ‘Reflexive engagement? Actors, learning and reflexivity in public dialogue on science and technology’. Science Communication 35 (3), pp. 283–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012454598 .

-

Cohen, D. and Crabtree, B. (2006). ‘Qualitative Research Guidelines Project. Semi-structured interviews’. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation . URL: http://www.qualres.org/HomeSemi-3629.html (visited on 21st July 2019).

-

Cross, N. (1982). Designerly ways of knowing .

-

— (2001). ‘Designerly Ways of Knowing: Design Discipline versus Design Science’. Design Issues 17 (3), pp. 49–55. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1511801 .

-

Cunliffe, A. L. (2016). ‘“On Becoming a Critically Reflexive Practitioner” Redux’. Journal of Management Education 40 (6), pp. 740–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562916668919 .

-

Davies, S. R. and Horst, M. (2016). Science Communication: culture, identity and citizenship. London, New York and Shanghai: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50366-4 .

-

Design Council (n.d.). What is the framework for innovation? Design Council’s evolved Double Diamond . URL: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/what-framework-innovation-design-councils-evolved-double-diamond (visited on 30th August 2021).

-

Fook, J. (2015). ‘Reflective practice and critical reflection’. In: Handbook for Practice Learning in Social Work and Social Care. Ed. by J. Lishman. 3rd ed. London, U.K and Philadelphia, U.S.A.: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

-

Grimm, P. (2010). ‘Social Desirability Bias’. In: Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. American Cancer Society. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444316568.wiem02057 .

-

Hächler, B. (2015). ‘Museums as Spaces of the Present: The Case for Social Scenography’. In: The International Handbooks of Museum Studies. Trans. by N. Hoskin, pp. 349–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118829059.wbihms316 .

-

Horst, M. (2011). ‘Taking Our Own Medicine: On an Experiment in Science Communication’. Science and Engineering Ethics 17 (4), pp. 801–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-011-9306-y .

-

— (2013a). ‘A Field of Expertise, the Organization, or Science Itself? Scientists’ Perception of Representing Research in Public Communication’. Science Communication 35 (6), pp. 758–779. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547013487513 .

-

— (2013b). ‘Learning from Discomfort: Science Communication Experiments Between Diffusion, Dialogue and Emergence’. In: Knowledge and Power in Collaborative Research. A Reflexive Approach. Ed. by L. Phillips, M. Kristiansen, M. Vehviläinen and E. Gunnarsson. 1st ed. Routledge. URL: https://www.routledge.com/Knowledge-and-Power-in-Collaborative-Research-A-Reflexive-Approach/Phillips-Kristiansen-Vehvilainen-Gunnarsson/p/book/9781138920613 .

-

— (2021). ‘Science Communication as a Boundary Space: An Interactive Installation about the Social Responsibility of Science’. Science, Technology, & Human Values . https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211003662 .

-

Horst, M. and Michael, M. (2011). ‘On the shoulders of idiots: re-thinking science communication as ‘event’’. Science as Culture 20 (3), pp. 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2010.524199 .

-

Irwin, A. (2014). ‘Risk, science and public communication: Third-order thinking about scientific culture’. In: Routledge Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology. Ed. by M. Bucchi and B. Trench. 2nd ed. London, U.K. and New York, U.S.A.: Routledge, pp. 160–172. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203483794 .

-

Jenkins, K. (2018). ‘"Can I see your social license please?"’ Policy Quarterly 14 (4), pp. 27–35. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v14i4.5146 .

-

Khoury, C. K., Kisel, Y., Kantar, M., Barber, E., Ricciardi, V., Klirs, C., Kucera, L., Mehrabi, Z., Johnson, N., Klabin, S., Valiño, Á., Nowakowski, K., Bartomeus, I., Ramankutty, N., Miller, A., Schipanski, M., Gore, M. A. and Novy, A. (2019). ‘Science-graphic art partnerships to increase research impact’. Communications Biology 2 (1), pp. 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0516-1 .

-

Latour, B. (2008). ‘A Cautious Prometheus? A Few Steps Toward a Philosophy of Design (with Special Attention to Peter Sloterdijk)’. In: Proceedings of the 2008 Annual International Conference of the Design History Society (Falmouth, U.K. 3rd–6th September 2009). Ed. by F. Hackne, J. Glynne and V. Minto, pp. 2–10. URL: http://www.bruno-latour.fr/node/69 .

-

Lewis, S. J. and Russell, A. J. (2011). ‘Being embedded: A way forward for ethnographic research’. Ethnography 12 (3), pp. 398–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138110393786 .

-

Lynch, M. (2000). ‘Against Reflexivity as an Academic Virtue and Source of Privileged Knowledge’. Theory, Culture & Society 17 (3), pp. 26–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/02632760022051202 .

-

Malpass, M. (2017). Critical design in context: History, theory, and practices. 1st ed. London, U.K.: Bloomsbury Academic. URL: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/critical-design-in-context-9781472575180/ .

-

Mattelmäki, T. (2005). ‘Applying probes — from inspirational notes to collaborative insights’. CoDesign 1 (2), pp. 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15719880500135821 .

-

Mejlgaard, N. (2018). ‘Science’s disparate responsibilities: Patterns across European countries’. Public Understanding of Science 27 (3), pp. 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662517724645 .

-

Metcalfe, J. (2019). ‘Comparing science communication theory with practice: an assessment and critique using Australian data’. Public Understanding of Science 28 (4), pp. 382–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662518821022 .

-

Michael, M. (1998). ‘Between citizen and consumer: multiplying the meanings of the “public understanding of science”’. Public Understanding of Science 7 (4), pp. 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/7/4/004 .

-

— (2012). ‘“What Are We Busy Doing?”’ Science, Technology, & Human Values 37 (5), pp. 528–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243911428624 .

-

Rogers-Hayden, T. and Pidgeon, N. (2007). ‘Moving engagement “upstream”? Nanotechnologies and the Royal Society and Royal Academy of Engineering’s inquiry’. Public Understanding of Science 16 (3), pp. 345–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662506076141 .

-

Salmon, R. A., Priestley, R. K. and Goven, J. (2017). ‘The reflexive scientist: an approach to transforming public engagement’. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 7 (1), pp. 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-015-0274-4 .

-

Salmon, R. A. and Roop, H. A. (2019). ‘Bridging the gap between science communication practice and theory: Reflecting on a decade of practitioner experience using polar outreach case studies to develop a new framework for public engagement design’. Polar Record 55 (4), pp. 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0032247418000608 .

-

Sanden, M. van der and Meijman, F. J. (2012). ‘A step-by-step approach for science communication practitioners: a design perspective’. JCOM 11 (02), A03. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.11020203 .

-

Sanders, E. B.-N. (2014). ‘Co-designing can seed the landscape for radical innovation and sustainable change’. In: The Highways and Byways to Radical Innovation — Design Perspectives. Ed. by P. R. Christensen and S. Junginger. Design School Kolding and University of Southern Denmark, pp. 133–151.

-

Stocklmayer, S. M. (2013). ‘Engagement with Science: Models of Science Communication’. In: Communication and engagement with science and technology. Issues and dilemmas. Ed. by J. K. Gilbert and S. M. Stocklmayer. London, U.K. and New York, U.S.A.: Routledge, pp. 19–38. URL: https://www.routledge.com/Communication-and-Engagement-with-Science-and-Technology-Issues-and-Dilemmas/Gilbert-Stocklmayer/p/book/9780415896269 .

-

Taffe, S. (2018). ‘Generate don’t evaluate: how can codesign benefit communication designers?’ CoDesign 14 (4), pp. 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1399144 .

-

Trumbo, J. (1999). ‘Visual Literacy and Science Communication’. Science Communication 20 (4), pp. 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547099020004004 .

-

Tschimmel, K. (2012). ‘Design Thinking as an effective toolkit for innovation’. In: Proceedings of the XXIII ISPIM Conference: Action for Innovation: Innovating from Experience (Barcelona, Spain, 12th–20th June 2012). URL: https://cordis.europa.eu/event/id/127911-the-xxiii-ispim-conference-action-for-innovation-innovating-from-experience-will-be-held-in-b/it .

-

Wallace, J., McCarthy, J., Wright, P. C. and Olivier, P. (2013). ‘Making design probes work’. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 3441–3450. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466473 .

-

West, K., Wilson, D., Thompson, A. and Hudson, M. (2020). Māori Perspectives on Trust and Automated Decision-Making. Digital Council. URL: https://digitalcouncil.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Maori-Perspectives-on-Trust-and-Automated-Decision-Making-13-Nov-2020-1.pdf .

Authors

Jo Bailey is a Senior Lecturer in visual communication design at The School of Design,

Massey University College of Creative Arts in Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand. She is

also a Principal Investigator with Te Pūnaha Matatini situated at the Centre for Science in

Society, Victoria University of Wellington exploring the intersection of design and science

communication.

E-mail:

j.bailey@massey.ac.nz

.

Rhian Salmon is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Science in Society, Victoria

University of Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand and a Principal Investigator with Te

Pūnaha Matatini. She is interested in strengthening the relationship between theory and

practice in Public Engagement with Science, especially with regard to engagement led by

scientists and science organisations.

E-mail:

rhian.salmon@vuw.ac.nz

.

Maja Horst is a Professor of Responsible Technology at the Danish Technological

University (Denmark) with an interest in Science Communication, Public Engagement

with Science and Responsible Innovation. She has also been experimenting with

interactive installations communicating her own research to the public.

E-mail:

majho@dtu.dk

.

Endnotes

1 A brief note on the term design: ‘Design has not one, but many shapes’ [Bason, 2017 , p. 36]. The authors consider design practice to encompass both a process (including methods and techniques), and the outputs generated by that process (artefacts, environments, experiences). Further, it refers to a mindset [Sanders, 2014 ] or attitude [Bason, 2017 ] that is comfortable with the ambiguity of non-predetermined outcomes, embraces iteration, and is human-centred. As a practice it can ‘bring the foundational skills of visualisation, problem solving and creativity to a collective level and seed the emergence of transdisciplinary approaches’ [Sanders, 2014 , p. 133] and within this research, it draws on the ‘participatory practices of making, telling and enacting’ [Sanders, 2014 , p. 140]. This is explored more fully in section “Using design in PES”

2 For clarity, we use science communication as an umbrella term for non-expert-facing communication that can include both one-way knowledge-transfer activities and PES approaches that include knowledge exchange and/or coproduction components.

3 For example, one participant made a ‘sewing tool’ to help integrate an indigenous worldview with a Western science perspective to help bring their whole self to their science communication; another made a ‘black box’ in which any logistical challenges could be fixed. This helped seed discussions about personal motivations, and also how to handle pragmatic administrative or practical issues.

4 Following Salmon, Priestley and Goven [ 2017 ] we use the term ‘scientist-communicator’ to indicate scientists who are undertaking their own science communication activities, to differentiate them from other science communication practitioners such as institutional public-relations staff or professional engagement consultants.

5 In the context of this paper, use of the term ‘design’ implies human-centred design (HCD). This approach is sometimes categorised as ‘Design Thinking’, especially when commodified for application outside the discipline, as a tool for innovation [Tschimmel, 2012 ]. Though HCD centres the human experience, it does not follow (as nascent discussions in the design field posit) that it does so at the expense of broader ecological systems.

6 The participants’ framing of their project (as science communication, engagement, outreach etc) was deliberately unquestioned, but the nuance of terminology became a discussion point during the EI.

7 Two authors coded the transcripts seperately and then compared themes, prior to a full discussion with the three-author team. The resonant themes were the value of design [18 occurrences], collective social experience [15] and resonant PES content [5]. These include sub-themes related to care [3], the creation of a safe space [4] and the process being permission-giving and providing social license [5].

8 It is interesting to note that our own reflexive process revealed that one of our implicit goals was to demonstrate to our colleagues what PES research can look like. This was partly because many of our science-grounded colleagues were confused by what ‘science communication research’ means, often assuming it primarily takes on a service role.

9 The authors have noted the resonance and value of this reproductive, repetitive facet of the laundromat concept several times since the 2020 EI. In 2021, at the TPM annual hui (gathering) for all investigators, one of the leaders spoke, unprompted, of public engagement being “like doing your washing”, suggesting this mindset (and vocabulary) has become embedded within the TPM culture. At the end of 2021, another EI was advertised (subsequently postponed due to the omicron Covid wave), and participants who had attended the first one requested to attend again for a second time. This suggests that the EI provides something beyond a ‘one-off’ introductory science communication workshop.