1 Introduction & objectives

Complex political decisions also increasingly require scientific knowledge and expertise. But the exchange between actors from the political and the scientific systems is confronted by challenges: there is relatively little incentive for scientists to invest resources in communication with political actors. The scientific system primarily rewards the communication of knowledge and findings in specialist media and among the professional public. That is why the communication of scientists predominantly follows the logic of scientific production and dissemination, which, in light of the complexity and terminology, is only compatible with the political logic to a limited extent [cf. Frohn, 2017 ; Tremblay, Vandewalle and Wittmer, 2016 ; Bednarek et al., 2018 ]. Furthermore, some scientists do not have the time resources or communication skills required to convey their knowledge to the political/administrative system [cf. Beratan and Karl, 2012 , p. 211].

On the other hand, actors in the political system only selectively address scientific actors and their findings, depending on their political demands and opportunities. Research distinguishes between three possibilities of using scientific knowledge [cf. Rimkutė and Haverland, 2015 , p. 432; Amara, Ouimet and Landry, 2004 ]: politicians and civil servants use scientific findings to a) develop solutions for social problems (instrumental knowledge utilisation), b) scientifically support already developed solutions (substantiating knowledge utilisation) or c) give more weight to their own positions and points of view (legitimising knowledge utilisation). The use of scientific knowledge therefore takes place in the framework of political action logics. In temporal, substantive and social terms, the two groups of actors act in accordance with different institutional expectations. Beratan and Karl [ 2012 , p. 190] sum up: “Scientists and decision makers come from dissimilar professional cultures with different purposes, values, norms, and reward systems. As a result, the two groups tend to approach problems and issues very differently, with little incentive on either side to change and broaden their horizons.”

Intermediary actors are required, in order to overcome or reduce these barriers to communication. Science policy interfaces could help, because they build platforms by means of which scientific findings are compiled and presented to the public. From these platforms, they reach different social actors — from parliamentary actors and actors in public administration to social interest groups and, last but not least, the citizens as electorate and as private actors [Lange, 2010 , p. 202].

In this context, foundations, which are growing in significance as part of society’s intermediary structure [cf. Scott, Lubienski et al., 2014 ], are playing an increasingly important supply and mediation role in the dissemination, discussion and reflection of scientific knowledge [cf. Scott and Jabbar, 2014 ]. This is also because, as private actors, they are free in their choice of topics, as well as in their strategy decisions, and do not have to seek direct approval. They can address problems and themes that may have social importance over the medium- or even long-term. In doing so, they can refer to scientific findings and sponsor related work. However, they are not always subject to scientific quality standards or transparent selection criteria. In addition, their studies are not always subject to scientific peer review procedures.

Social commitment combined with scientific expertise is increasingly apparent among larger German foundations (such as the Stiftung Mercator in the area of climate change or the Hertie Stiftung in the area of governance). Foundations advocate selective goals, facilitate scientific analyses to this end, and transmit scientific knowledge. They are involved in or initiate the founding, as well as funding, of research institutions, think tanks, consultancies, etc. In addition, operationally active foundations, in particular, act on their own or with other actors to provide policy recommendations, consultancy models etc. Foundations themselves also transmit scientific knowledge or contribute to transferring them to certain sectors of society.

This article analyses and discusses the importance of foundations as science policy interfaces. To this end, we will first present the salient features and functions of foundations as actor-type in the framework of theoretical considerations and discuss their fundamental suitability as mediators of scientific knowledge in the political process. We will then identify the significance and role of foundations as science policy interfaces using a quantitative content analysis of references to foundations in the debates of the 18th German Bundestag.

2 Foundations as science policy interfaces

The term “science policy interfaces” is used to describe the mediation between science and politics via “intermediaries”, “brokers”, “mediators” or “science communicators” [cf. Knight and Lyall, 2013 ; Rodari, Bultitude and Desborough, 2012 ; Peters, 2013 ]. van den Hove [ 2007 , p. 814–815] defines them as “social processes which encompass relations between scientists and other actors in the policy process, and which allow for exchanges, co-evolution, and joint construction of knowledge with the aim of enriching decision making.” But the constitution as well as the governance of these intermediaries, which act alongside other intermediaries such as parties or associations, involves many presuppositions. They need to have their focus in the area of science, as well as to have a certain degree of autonomy, in order to be credible. Above all, however, they must not enter into competition with the intermediaries competing for votes, to fill posts or directly to advance interests — since this is the domain especially of political parties (interest promotion) and associations (interest aggregation). Sarkki et al. [ 2013 ] therefore consider credibility, relevance and legitimacy to be decisive characteristics for the efficiency and improvement of the use of scientific knowledge in political will formation and decision-making. Besides the classical actors in the science sector, such as universities, universities of applied sciences and academies [cf. Fähnrich, 2018 ], foundations can also be increasingly identified as science policy interfaces [cf. Frohn, 2017 ; Hamburg, 1999 ].

A wide range of different actors with various goals, organisational structures, legal structures (in Germany: civil law foundation; gGmbH [charitable] foundation, GmbH foundation, fiduciary foundation, association, among others), financial means, and modes of operation can be subsumed under the concept of foundation [cf. Adloff, 2004 , p. 272; Kocka, 2004 , p. 5]: “In the nonprofit sector, the term foundation has no precise meaning” (Council on Foundations: Foundations Basics 1 ). What they have in common is that they constitute a legal person, usually of a permanent nature, whose assets are used for a foundation purpose determined by the donor [cf. Strachwitz, 2010 ]. The European Foundation Center specified possible foundation purposes as follows: “They distribute their financial resources for educational, cultural, religious, social or other public benefit purposes, either by supporting associations, charities, educational institutions or individuals, or by operating their own programmes (European Foundation Center).” 2 The purpose of the foundation needs to be anchored in a statute that is designed such that this statute permanently binds the administrator of the body with regard to the preservation and use of the assets [Strachwitz, 2011 , p. 348]. Foundations are often assigned to the domain of civil society, since they “neither belong to the public sphere nor to the market and are also not situated in the private sphere” [Kocka, 2004 , p. 4].

They can influence political processes in many ways. In so doing, their action, unlike, for instance, that of parties and associations, normally does not require legitimation by member votes or public monitoring. This enables them to act independently of fully formulated or even declared normative standpoints, the obligation to participate in elections or on the basis of third party requirements. On the other hand, foundations often find that they are confronted by questions of legitimacy owing to these specific characteristics [Fritsch, 2007 , p. 165ff], since they function as private actors and are only subject to limited public oversight, even though they react to public affairs or make reference to public issues. Above all, party- and corporate-affiliated foundations find themselves confronted by such criticism, when they engage in fields of research that are closely connected to their political expertise or business area [cf. Rohe, 2016 ]. In order to be successful, they must therefore be concerned for their own legitimacy — especially when they explicitly pursue political goals. This requires a certain amount of transparency from foundations, as well as suitable governance.

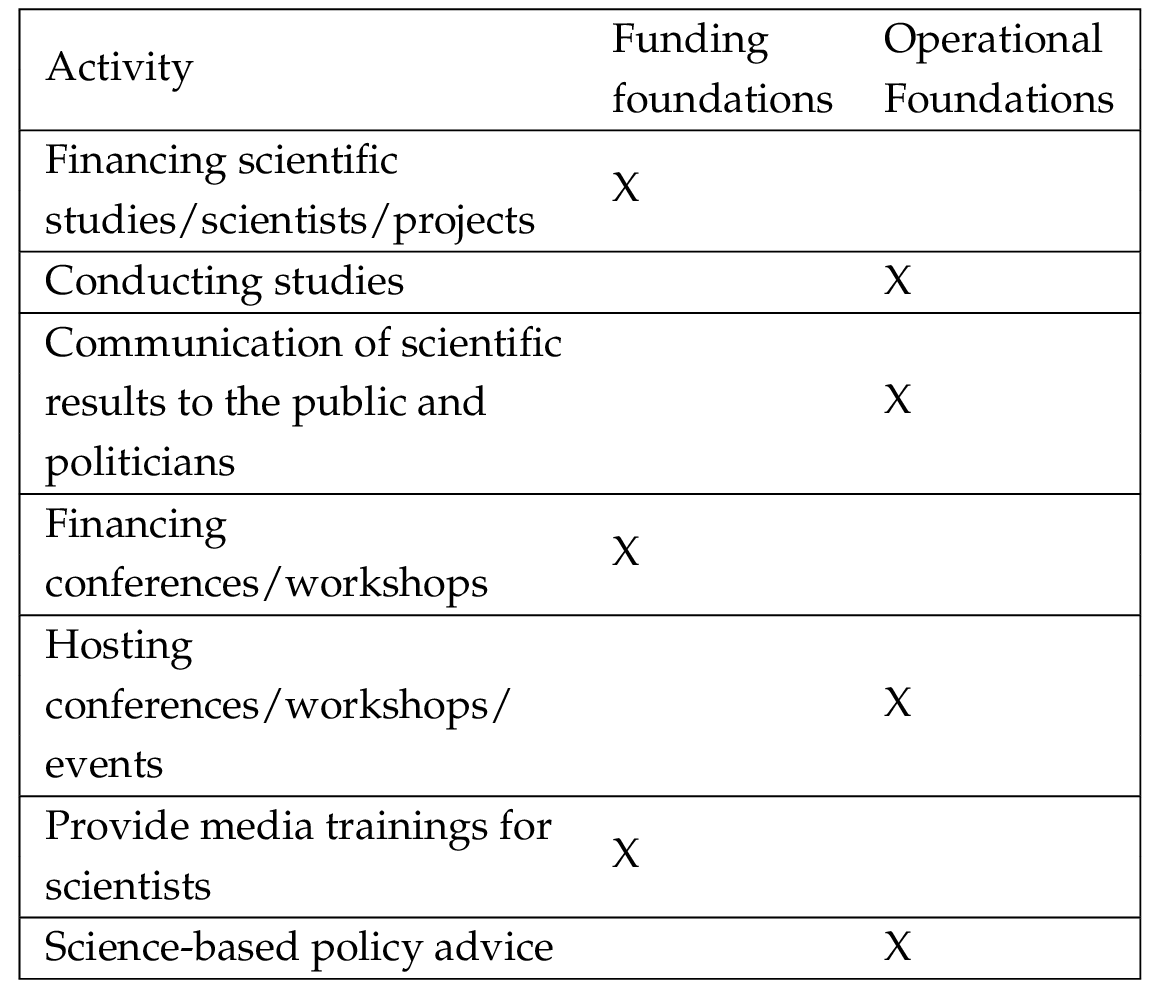

A fundamental distinction can be made between two types of foundations, which differ as regards the involvement of external actors: on the one hand, operational foundations can be identified, which carry out their own projects [including, among other things, research projects, political consultancy, competitions; cf. Leat, 2016 ; Wigand, 2009 , p. 168]. They must be distinguished from funding foundations, which promote external projects or actors: for example, via scholarships, grants, and research funding, among other things [cf. Strachwitz, 2011 , p. 353]. The distinction between operational and funding foundations is not always clear-cut, however: many foundations, as mixed types, are active both operationally and in providing funding.

For the most part, foundations perform important social, charitable, economic or also political tasks [cf., among others Adloff, 2004 , p. 274]: they operate as promoters of innovative ideas [Adloff, 2004 , p. 280], as political consultants [cf. Welzel, 2006 ], as initiators of scientific projects or as an “instrument of institutional mediation between different social sub-sectors” [Adloff, 2004 , p. 280]. Foundations increasingly appear in the role of science policy interfaces, above all, by financing, promoting and conducting scientific studies, projects and scientific actors, as well as by making available and disseminating scientific expertise to political actors [cf. Frohn, 2017 , p. 452; Hamburg, 1999 ]. They also create public and non-public spaces of interaction for politicians and scientists in the framework of events, workshops and discussion groups, “allowing ideas to flow through a great permeable membrane between government and nongovernment bodies and helping to provide for a mutually beneficial flow of information and people between the governmental and nongovernmental sector” [Hamburg, 1999 , p. 259]. Furthermore, they initiate and are responsible for scientific public relations campaigns [Weingart, 2012 , p. 21] or provide media training for scientist [Peters, 2012 , p. 225]. For operational foundations the function of political consultancy can also be added: in other words, collecting or producing information, disseminating it to political actors, and support or guidance in decision-making [cf. Welzel, 2006 , p. 278]. They are even regarded, at least in certain policy fields, as “major players in policy making” [Anheier, 2015 ], which exercise their influence on the political decision-making process by sharing knowledge. Operational foundations therefore often position themselves as think tanks or are perceived and systematized as such [cf. Ruser, 2018 , p. 44; Thunert, 2004 , p. 71]. Think tanks are independent research organizations that provide applied research to political decision makers [cf. Ruser, 2018 , p. 44] and therefore also include other organizations that are not organized as foundations, such as, for instance, the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development or the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research. Moreover, not all foundations act as think tanks. For this study it is assumed that foundations that do not carry out research themselves but promote it and communicate their results can also function as important science policy interfaces. Both actor terms therefore have overlaps, but cannot be used synonymously.

In this connection, as compared to parties and associations, they can decide more freely which topics and problems require attention, due to less “internal and external constraints” [Fraussen and Halpin, 2017 ]. However, since think tanks also carry out research independently, without always having to fulfil scientific quality criteria, Sebba [ 2013 ] challenges their suitability and efficiency as “research mediators”.

As a preliminary conclusion, it can be noted that foundations pursue an aim defined by the donor and mostly realised with the resources of the latter. Unlike other scientific organizations such as universities or academies, foundations do not have to compete for money, students or the goodwill of their members. They are thus more free in their decision-making. At the same time, however, this also means that their actions are not subject to any formal control mechanism. This raises questions of legitimacy. Some of these foundations — above all, operationally active ones — promote scientific projects and studies or have their own projects and studies prepared, organise conferences, and employ experts by virtue of whose knowledge and recommendations they qualify as science policy interfaces for political decision-makers, in order thereby to exert influence on social processes. The following table 1 provides an overview of the science-based main activities of funding and operational foundations.

They play a “discernible role in the policy process and […] they are relevant political actors. Not only are they worthy of academic analysis; they also demand the attention of politicians and political observers and the vigilance of those interested in open political processes [Pautz, 2012 , p. 181]. ” Despite this importance of foundations for conveying scientific knowledge in politics and the public sphere, however, there are hardly any scientific — especially empirical — analyses on this subject for the German-speaking area [cf. Almog-Bar and Zychlinski, 2014 ].

The majority of publications discuss the significance of foundations theoretically and conceptually [cf. Anheier, 2015 ; Strachwitz, 2010 ; Kocka, 2004 ] or represent reflections of practitioners or science managers [Frohn, 2017 ; Rohe, 2016 ].

Studies that focus on the analysis of think tanks, however, only consider a small part of the organizations that are organized as foundations. For example, Ruser [ 2018 ], who analysed foundations acting as think tanks on the subject of climate policy, can show in network analyses of cooperation and client relations that party foundations do not play a central role compared to academic think tanks. However, this finding is regarded by the author as misleading because “A closer look at these particular organizations, however, reveals that political foundations have been active in providing political expertise on climate politics” [Ruser, 2018 , p. 114]. Thunert [ 2004 , p. 85] certifies above all that party-related foundations, which he calls party think tanks, have an influence in the early stages of the policy process and in the area of the inner-party opinion-forming process. Studies, that are mostly based on interview data with representatives of think tanks, also showed that think tanks can play a relevant role in the policy making process in Australia [Fraussen and Halpin, 2017 ], the U.S.A. [Grossmann, 2012 ] and Great Britain [Pautz, 2013 ], especially by providing research results to political actors. An interviewee of a think tank from Grossmann’s study leads to “They believe our numbers are accurate. We have a reputation for solid research.” [Grossmann, 2012 , p. 162].

In addition, foundations and scientific knowledge provided by foundations are not specifically taken into account in studies dealing with the use of scientific findings by politicians and administrations. The studies, which are often based on survey data, only analyse in general whether scientific findings are taken into account or specifically ask only about the significance of university studies for specific policy fields [Boswell, 2008 ; Boswell, 2009 ; Haverland, 2009 ; Schrefler, 2010 ].

Content analytical studies of parliamentary debates have also not focused on the importance of foundations [Vowe, 2006 ; Vowe and Dohle, 2009a ; Vowe and Dohle, 2009b ; Scherer and Baumann, 2002 ]. They have not differentiated categories such as supranational and international organisations and experts any further. Thus, it remains unclear to what extent foundations and foundation representatives may be classified under these categories. The significance of foundations in the parliamentary debate cannot therefore be comprehended.

The objective of the present study is to close a specific research gap as regards the possible role of foundations as science policy interfaces.

Therefore, the present study focuses on the question as to whether parliamentary discourse refers to studies/projects that were commissioned by foundations or studies/expert reports conducted by them (F1.1) and whether the expertise of foundations is taken into account in parliamentary discourse (F1.2)? How the foundations and their activities are evaluated in parliamentary discourse (F2) is also of interest, since it can be assumed that the effectiveness of knowledge-mediating processes is especially influenced by how the transmitter of the knowledge is assessed. Finally, we will assess whether party-specific differences are apparent in the use of references to foundations (F3).

3 Method & design

In order to answer the research questions, we relied on a quantitative content analysis of the parliamentary debates of the 18th German Bundestag (October 2013–October 2017).

The case study analyses the importance of German foundations for the mediation of science in parliamentary discourse for the following reasons:

- After the U.S.A., Germany has the largest and most resource-rich foundation system [Anheier et al., 2017 , p. 12]. The Bundesverband deutscher Stiftungen [Federal Association of German Foundations] [Bundesverband deutscher Stiftungen, 2019 , as of 22.01.2019] currently lists more than 22,000 foundations. The majority is exclusively active in the non-profit sector. For this reason, German parliamentarians are expected to take this important societal actor into account.

- In Germany, there are also numerous foundations under public law which are characterised by a special proximity to state actors [Anheier et al., 2017 , p. 12]. These include, for example, cultural and scientific foundations such as the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz [Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation], Conterganstiftung [Contergan Foundation] and Cultural Foundations of the State. Especially here the attention of politicians to the foundation’s activities seems probable.

- All parties represented in the Bundestag also have party-related foundations [Renvert, 2011 , p. 356; Anheier et al., 2017 , p. 14]. This cannot be found in any other country.

- In addition, the German Bundestag allows a simple keyword search in the parliamentary minutes.

The following parliamentary groups were represented in the 18th Bundestag: the Christian Democratic Union (CDU)/Christian Social Union (CSU, with a total of 309 deputies) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD, with 193 parliamentarians), which formed the governing coalition, as well as the opposition parties Bündnis 90/die Grünen [Greens] (63 deputies) and Die Linke [ Left ] (64 deputies). While the CDU/CSU can be located in the conservative bourgeois party spectrum, the SPD, the Greens and also the Left are positioned primarily in the social and left-wing party milieu. The core competence of the CDU/CSU is above all economic expertise. The SPD and the Left are awarded expertise in the social field. Environmental protection and nature conservation are classically part of the competence of the Greens [cf. Niedermayer, 2015 , p. 16].

The debates were searched using the German Bundestag database. 3 The word “Stiftung [foundation]” was used as search term. The advantage of this approach was that it enabled all references to individual foundations or the general foundation sector to be taken into account. In addition, it was also possible to identify foundations relevant for scientific mediation ex post and hence completely, rather than creating a list of foundation names ex ante, which would have then served as search terms. However, the disadvantage is that foundations operating under a name not including the term “foundation” could not be found with the chosen search term. Similarly, it was not possible to include sub-organisations and subsidiaries of foundations that were founded for a specific purpose, but that operate under a different name. Studies, rankings, projects or expert reports by foundations, but whose issuer was not made transparent in the parliamentary debate itself, were also not taken into account. This search term displayed 194 parliamentary proceedings in the list of hits for the 18th legislative period. The analysis was based on a representative random sample of the parliamentary debates. A total of 149 proceedings were analysed — of which approx. 14% (n=21, 95% KI [8.7; 20.1]) were accounted for by the policy area “international politics”, as well as 13% each (n=20, 95% KI [8.1; 18.8]) by debates in educational policy and financial policy.

In addition to the formal features such as date, policy field or subject of the debate, data was also collected on the following variables at statement level. The formal categories for the analysis of parliamentary minutes originate from the language-analytical study of parliamentary debates [Jarren, Oehmer and Wassmer, 2010 ]. The content variables for the foundation references were mainly developed inductively in parts of the analysis material. On the other hand, the categories were deductively derived from studies that dealt empirically with foundations [Donsbach and Brade, 2013 ]. The inter-coder reliability coefficient (Krippendorff’s Alpha) of four coders was specified in brackets for each category:

- Content of the foundation statement (.87): this variable was used to determine what the statement on the foundation is about. A distinction was made, on the one hand, between general information (for example, publication of a foundation’s annual report or a change in the management) and the different forms of social(-political) activities of a specific foundation (including campaign/initiative, projects/funding plans, studies/ expert reports, award ceremonies; competition; scholarships; conference/meeting/discussion group/podium discussion, consultancy activities, submission of a petition, participation in legislative projects). Also, general statements about foundations or the foundation sector (for example, reference to the work/functions of foundations, calls for transparency from foundations, financial support) were coded.

- Functional role of the foundation in the statement (.76): data was also collected on what role a foundation plays in the reference: if it was mentioned in connection with expert knowledge — for example, by citing study results or assessments of substantive issues — then it was coded as expert. The advocacy role was coded, if the foundation appeared as defending a specific position. If, however, the main focus was on the foundation activities — such as competitions, initiatives or campaigns — which were initiated, in order to place a specific topic on the political or social agenda, the role of the agenda-setter was coded. If the parliamentarian placed the emphasis on the foundation’s third party funding activities (for example, awards given to scientists, project support…), then it was coded in the role of funder.

- Assessment of the foundation (.94): the assessment of the foundation was recorded as positive, neutral, negative, and not clear.

- Party/parliamentary group of the statement source (1): data was also collected on the party affiliation (CDU/CSU, SPD, The Greens, The Left Party [ Die Linke ], independent) of the source of the statement on the foundation, in order to identify possible differences in political orientation.

In addition, the coders were instructed to record the respective foundation names and statements as a direct quote. Some of these are reproduced in the results chapter for illustration purposes.

4 Results

A total of 711 statements referring to foundations were identified in the parliamentary debates. The Bertelsmann Stiftung (n=46) and the Alexander-von-Humboldt-Stiftung (n=27) are the most frequently mentioned foundations. They are followed by the party-affiliated foundations such as the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (n=22) and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (n=21), which, above all, via the persons on the foundations’ governing bodies, are closely linked to the respective parties and their objectives [cf. Heisterkamp, 2014 ]. The majority of statements referring to foundations can be attributed to parliamentarians from the CDU/CSU (32.9%, n=234, 95% KI [29.7; 36.4]) and the SPD (27.3%, n=195 KI [23.8; 30.7]) and therefore from the largest parliamentary groups (those of the governing parties with a total of 502 members of to parliament) in the 18th German Bundestag. Far behind, there then follow references to foundations from Left Party politicians (16.3%, n=116. 95% KI [13.5; 19.1]) and politicians from the Greens (13.8%, n=98, 95% KI [11.4; 16.3]). Independent parliamentarians commented on foundations in 59 cases (8.3%, 95% KI [6.5; 10.3]). Foundations are, above all, mentioned in financial policy debates (24.3%, n=173, 95% KI [21.1; 27.6]). In addition, they are also cited in the context of cultural (8.4%, n=60, 95% KI [6.3; 10.5]) and socio-political (7.0%, n=50, 95% KI [5.3; 9.0]) debates. This also supplements the findings of the study by Amara, Ouimet and Landry [ 2004 , p. 99], which were able to demonstrate a recourse to university research findings, particularly in the policy fields of education and social services. They are also taken into account during discussions on international politics (6.9%, n=49, 95% KI [5.1; 8.7]).

4.1 Content of the reference to foundations

Firstly, the question (F.1.1) was addressed regarding the content of references to foundations and whether studies/projects that were commissioned by foundations or studies/expert reports conducted by the latter entered into parliamentary discourse. On the one hand, a distinction was made between statements containing information or activities from a specific foundation. On the other hand, general references on foundations and the foundation sector were identified.

A large part of the statements contain — predominantly organisational — information about foundations, such as their financial resources, for instance, or elections to the management board (32.6%, n=232, 95% KI [29.3; 36.1]), and thus do not contain any content that is relevant for scientific mediation. Nevertheless, attention is given to foundations and their activities in parliamentary debates. However, when the activities of foundations were addressed, the activities in question were studies and reports conducted, published or commissioned by them (17.9%, n=127, 95% KI [15.1; 20.7]); they are therefore relevant as bearers or mediators of knowledge. Such references included statements like “The results of the current 2016 Regional Monitoring of Early Childhood Education by the Bertelsmann-Stiftung demonstrate that the quality development process is already bearing fruit” (Protocol 18/228) or “The Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik [German Institute for International and Security Affairs] has recently published a rather clever, I find, analysis to this end” (Protocol 18/228). This shows that scientific knowledge coming from foundations is recognised and used for arguments in parliamentary debates.

In addition to the role of knowledge-mediator, foundations are also thematised in parliament as knowledge promoters and facilitators. In 9.3 % (n=66, 95% KI [7.2; 11.4]) of the statements referring to foundations, reference is made to studies and projects that have been sponsored or facilitated by foundations: statements such as “We now also have a platform funded by the Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt [German Environment Foundation], which provides the economy with analyses and instruments to reduce food losses” (Protocol 18/234) or “The projects that this foundation carries out include the archive of other memories…, a number of projects on the acceptance of gender and sexual diversity, as well as the active fight against homophobia: for example, in sport” (Protocol 18/119) were subsumed under this heading. Conventions and meetings that were initiated by the foundations were referred to on only 12 occasions in the debates (1.7%, 95% KI [0.8; 2.7]): among them were the following references:

“Only last year, in March 2014, the Foreign Office organised an international seminar in cooperation with the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, at which experts discussed in what way and by what steps, non-strategic nuclear weapons can, with Russian and American participation, be disarmed (Protocol 18/90)”.

“At a recent conference hosted by the Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS) addressed the federal states’ request for additional instruments, particularly those pertaining to the social labour market, by saying that an instrument reform would create too much disruption in the job centres (Protocol 18/101)”.

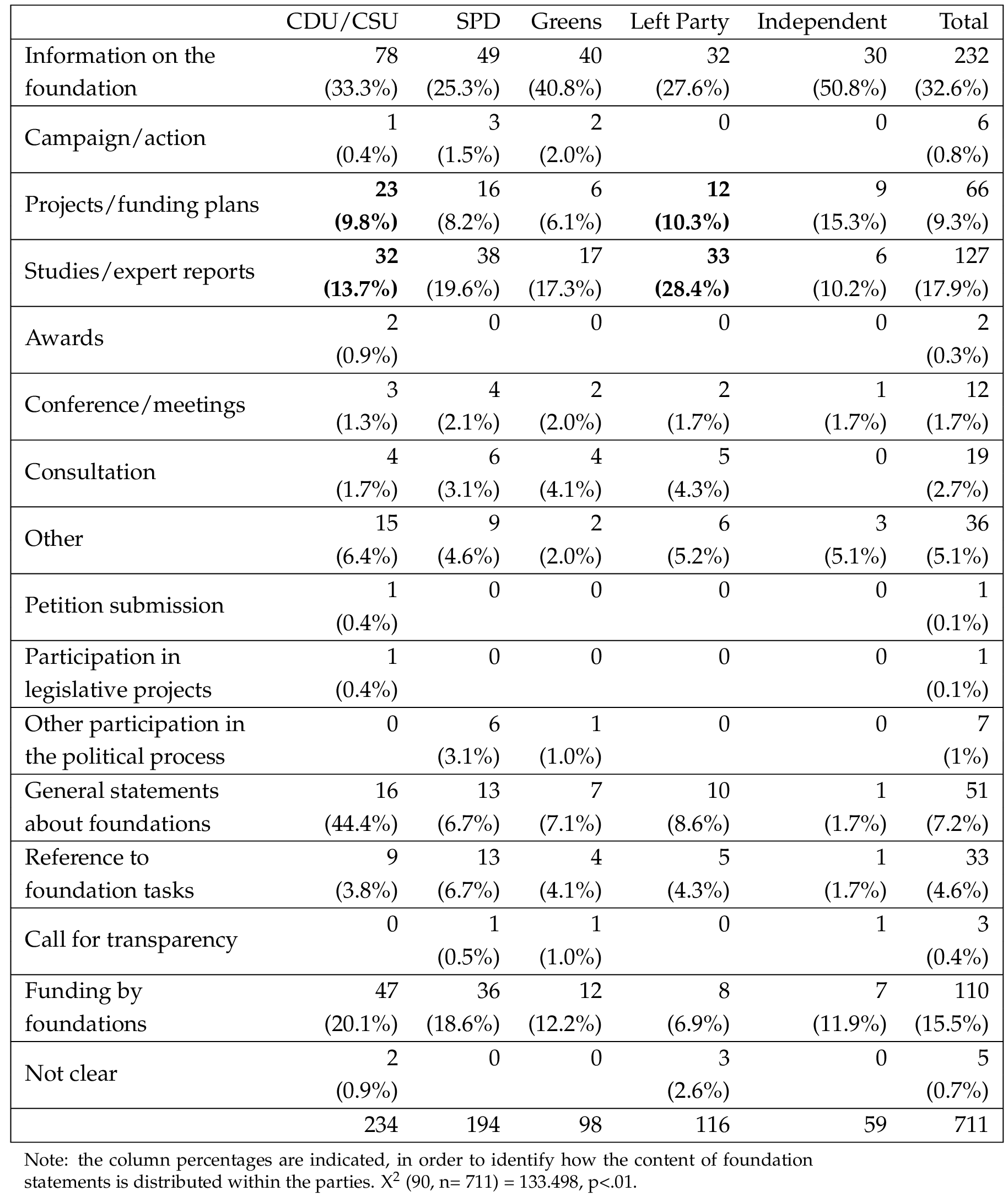

If one considers the contents of statements on foundations separately by Bundestag parliamentary groups, so as to answer research question 3, it is clear that, above all, the opposition party the Left Party has recourse to foundation knowledge from expert reports and studies or to projects/funding plans. Almost one third of all statements on foundations (28.4%, n=33, see table 2 ) from this parliamentary group’s members refer to findings of foundations from studies. 10.3 percent (n=12) of the statements refer to projects and funding plans. This may be due to the fact that the Left Party, as an opposition party, has less financial and organisational resources at its disposal than, for instance, the ruling parties, which can rely on expertise, assessments, opinions and research coming from the apparatus of government. Hence, it is perhaps more heavily reliant upon knowledge made available to it by third parties. By way of comparison: only 13 percent (n=32) of the references by the CDU/CSU parliamentary group have recourse to expert reports or studies. Projects and funding plans of foundations are only mentioned by CDU/CSU members in 9.8 percent (n=23) of the cases.

4.2 Functional role of the foundations

The functional role in which foundations appear in the statements was also identified (F1.2): the data encompassed the roles of expert, funder, advocate and agenda-setter. More than two thirds of the statements referring to foundations do not include any specific role ascription (55.4%, n=394, 95% KI [51.9; 59.2]). If, however, a role ascription can be identified, this is, above all, the expert role at 20.6% (n=146, 95% KI [17.7; 23.6]). Statements illustrating this include “The rotation of troops is a trick in order to circumvent the prohibition of permanent stationing — that was said, moreover, by Wolfgang Richter from the Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik — (Protocol 18/212).” Or: “But the dilemma is that due to the type of state founding that received massive support from the West — the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung also says this — precisely these hopes have not been fulfilled (Protocol 18/209).” Politicians thus use the knowledge made available by foundations both to justify and legitimise their own positions. Above all, politicians from the Left Party employ these means: 30.2 percent (n=35) of all references to foundations made by them refer to foundations’ expertise. Merely 16.2 percent (n=38) of all statements about foundations by CDU/CSU parliamentarians had foundations appear as experts. Foundations are also described by parliamentarians in the role of funder: they are portrayed as institutions that make possible projects or studies 117 times (16.5%, 95% KI [13.6; 19.1]). This is reflected in references such as:

“Major German foundations therefore endeavour, following the example of the German-Jordanian University, to establish a university of applied sciences in East Africa, in order to fill the gap between school and academic training, to educate in a more applied manner, because there is a corresponding need for this in these regions (Protocol 18/193).”

“The topic of ‘Forced Germanisation” has been addressed in the context of projects by way of various funding programmes of the Stiftung “Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” [Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future”] (Protocol 18/215).”

Parliamentarians barely cite foundations in the role of advocate (6.3%, n=45, 95% KI [4.6; 8.2]), defending its own positions, and agenda-setter (1.3 %, n=9.95% KI [0.6; 2.1] that introduces topics into the social debate.

4.3 Assessments of foundations

Since it is presumed that the role of a knowledge-mediating actor is shaped by how it is perceived, data was also compiled on the assessment of foundations in parliamentary debates (F2). Almost two thirds of the statements referring to foundations are neutral (72.7%, n=517, 95% KI [69.3; 76.2]). The remaining statements are almost entirely positive (20.5%, n=146, 95% KI [17.6; 23.5]). In principle, we can thus suppose a positive attitude towards and perception of foundations. Hardly any negative statements about foundations can be noted (2.5%, n=18, 95% KI [2.8; 5.8]). These are mostly articulated by representatives of the Left Party (7.8%, n=9) and largely refer to party-affiliated foundations of rival parties.

5 Discussion & conclusion

A key interest of the present study was the question concerning what role foundations play as science policy interfaces in parliamentary debates in the German Bundestag. Based on the results of the content analysis of parliamentary debates, it was possible to show that parliamentarians perceive foundations as knowledge-mediating institutions and that knowledge provided by foundations is introduced into the political debate. Thus, studies or expert reports of foundations are referred to, projects and funding plans are thematised or, albeit to a very limited extent, mention is made of conferences and meetings they host. They are mainly presented in the role of expert or funder and this, above all, for the purpose of legitimising one’s own political positions. Hence, foundation activities are predominantly integrated into the debate when they provide support from an independent third party for one’s own argument. In analogy to findings on the use of research results in politics and administration [Rimkutė and Haverland, 2015 ] and on the use of sources in journalism, an instrumental quotation of “opportune witnesses” [Hagen, 1993 ; Brüggemann and Engesser, 2014 ] can also be assumed here. This, however, requires additional (case-study) analyses, which also shed light on possible specificities of policy fields: it is thus interesting to illuminate in which policy fields foundations, and foundations as knowledge-mediators, act on a particularly frequent basis. On the other hand, they are not presented as advocates, which formulate and defend their own positions, or agenda-setters, which introduce socially relevant topics into the debate. Moreover, foundations mostly have positive or neutral connotations for parliamentarians, such that we can, in principle, assume a positive reception of foundation activities and knowledge.

Although knowledge imparted by foundations is primarily used to legitimize and strengthen one’s own positions, the study results can nevertheless be seen as an indication that foundations function as science policy interfaces. They show that their scientific knowledge is acknowledged, processed and used for argumentation by parliamentarians in debates. It is important to bear in mind that debates serve primarily to communicate arguments and interests to the public [Auel and Raunio, 2014 ]. It is therefore understandable that only studies and scientific findings that are conducive to one’s own argument are used here. However, it also seems plausible to assume that studies also play a role in (an earlier stage of) parliamentary work that is not addressed to the public, such as committee meetings and parliamentary group meetings. However, this could only be clarified by means of survey and interview studies which ask parliamentarians about the use of knowledge provided by foundations and about their attitude towards foundations as mediators of science. However, the answer to this question is reserved for future studies. Also interviews with foundation representatives, for example, could provide relevant insights into this aspect.

In addition to the classical science actors, foundations can assume a key role in mediating knowledge in political processes: a role that they are able to fulfil by virtue of the (in some cases) ample financial resources at their disposal. Moreover, unlike researchers at universities, their activity, which is, above all, communicative, is primarily aimed at extra-systemic, social target groups.

It should, however, be critically noted that studies carried out by (operational) foundations themselves — in contrast to the research projects of classical science actors at universities and academies — are not necessarily subject to scientific quality standards and oversight mechanisms such as, for instance, the peer-review process. As regards funding foundations, which facilitate projects by third parties such as researchers at universities and research institutions, the choice of projects mostly takes place according to considerations that have little transparency for the general public with regard to the foundation purpose [cf. Frohn, 2017 , p. 228]. Criteria of the scientific system, such as the suitability of the theoretical basis and the choice of method, as well as the project’s scientific and social relevance, do not always have to play a central role here. Furthermore, the political-ideological proximity of foundations to individual parties or interest groups and associations that sometimes exists also provokes scepticism as regards the neutrality of the knowledge generation and the communication of knowledge. Hence, an important premise for recognition as relevant science policy interfaces in the policy area is not satisfied. An interface function requires a specific governance, which also safeguards the quality of the scientific mediation. Otherwise, the knowledge made available and communicated by foundations could be discredited as partisan knowledge. Further research should therefore devote attention to the governance of foundations in the context of supplying knowledge as well as mediating (scientific) knowledge.

The study also provided insights into party differences: for instance, it is, above all, the Left Party that introduces the expertise of foundations into the debates. What needs to be clarified in the future is whether this represents a general pattern between resource-rich governmental and rather resource-poor opposition parties or whether political positions play a role in taking foundations into consideration.

The study solely focused on foundations and their role as science policy interfaces. For this reason, the debates to be analysed were also selected using a keyword search for this actor in the parliamentary proceedings database of the German Bundestag. A comparison with other knowledge-mediating actors and their significance in parliamentary discourse was therefore not possible. The identification of all knowledge mediating actors and their perception by politicians is reserved for future studies. Exclusively focusing on one legislative period also rendered it impossible to make statements about possible change in the importance of foundations in parliamentary work. A longitudinal design would be desirable here.

References

-

Adloff, F. (2004). ‘Wozu sind Stiftungen gut?’ Leviathan 32 (2), pp. 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11578-004-0018-4 .

-

Almog-Bar, M. and Zychlinski, E. (2014). ‘Collaboration between philanthropic foundations and government’. International Journal of Public Sector Management 27 (3), pp. 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijpsm-03-2013-0036 .

-

Amara, N., Ouimet, M. and Landry, R. (2004). ‘New evidence on instrumental, conceptual and symbolic utilization of university research in government agencies’. Science Communication 26 (1), pp. 75–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547004267491 .

-

Anheier, H. (2015). ‘Policy knowledge: foundations’. In: International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. The Netherlands: Elsevier, pp. 293–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-097086-8.75035-5 .

-

Anheier, H. K., Förster, S., Mangold, J. and Striebing, C. (2017). Stiftungen in Deutschland 1 — Eine Verortung. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-13369-6 .

-

Auel, K. and Raunio, T. (2014). ‘Debating the state of the union? Comparing parliamentary debates on E.U. issues in Finland, France, Germany and the United Kingdom’. The Journal of Legislative Studies 20 (1), pp. 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2013.871482 .

-

Bednarek, A. T., Wyborn, C., Cvitanovic, C., Meyer, R., Colvin, R. M., Addison, P. F. E., Close, S. L., Curran, K., Farooque, M., Goldman, E., Hart, D., Mannix, H., McGreavy, B., Parris, A., Posner, S., Robinson, C., Ryan, M. and Leith, P. (2018). ‘Boundary spanning at the science-policy interface: the practitioners’ perspectives’. Sustainability Science 13 (4), pp. 1175–1183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0550-9 .

-

Beratan, K. K. and Karl, H. A. (2012). ‘Managing the science-policy interface in a complex and contentious world’. In: Restoring lands — coordinating science, politics and action. Ed. by H. Karl, L. Scarlett, J. Vargas-Moreno and M. Flaxman. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Netherlands, pp. 183–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2549-2_10 .

-

Boswell, C. (2008). ‘The political functions of expert knowledge: knowledge and legitimation in European Union immigration policy’. Journal of European Public Policy 15 (4), pp. 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760801996634 .

-

— (2009). ‘Knowledge, legitimation and the politics of risk: the functions of research in public debates on migration’. Political Studies 57 (1), pp. 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00729.x .

-

Brüggemann, M. and Engesser, S. (2014). ‘Between Consensus and Denial: Climate Journalists as Interpretive Community’. Science Communication 36 (4), pp. 399–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547014533662 .

-

Bundesverband deutscher Stiftungen (2019). Statistiken . URL: https://www.stiftungen.org/stiftungen/zahlen-und-daten/statistiken.html (visited on 22nd January 2019).

-

Donsbach, W. and Brade, A.-M. (2013). Forschungsfördernde Stiftungen in der Wahrnehmung ihrer Stakeholder. [Abschlussbericht]. Dresden, Germany: Institut für Kommunikationswissenschaft, Technische Universität Dresden. URL: https://www.volkswagenstiftung.de/aktuelles-presse/publikationen/forschungsf%C3%B6rdernde-stiftungen-in-der-wahrnehmung-ihrer-stakeholder-studie-2013 (visited on 22nd January 2019).

-

Fähnrich, B. (2018). ‘Einflussreich, aber wenig beachtet? Eine Meta-Studie zum Stand der deutschsprachigen Forschung über strategische Kommunikation von Wissenschaftsorganisationen’. Publizistik 63 (3), pp. 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11616-018-0435-z .

-

Fraussen, B. and Halpin, D. (2017). ‘Think tanks and strategic policy-making: the contribution of think tanks to policy advisory systems’. Policy Sciences 50 (1), pp. 105–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-016-9246-0 .

-

Fritsch, N. (2007). ‘Erfolgsfaktoren im Stiftungsmanagement. Erfolgsfaktorenforschung im Nonprofit-Sektor’. Dissertation. Wiesbaden, Germany: University of Münster. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8349-9311-3 .

-

Frohn, R. (2017). ‘Stiftungen — Wissenschaften — Politik. Chancen und Grenzen wissenschaftlicher Politikberatung durch Stiftungen’. In: Fortsetzung folgt. Ed. by F. Hoose, F. Beckmann and A. Schönauer. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien, pp. 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-15450-9_21 .

-

Grossmann, M. (2012). The not-so-special interests: interest groups, public representation and American governance. Stanford, CA, U.S.A.: Stanford University Press.

-

Hagen, L. M. (1993). ‘Opportune witnesses: an analysis of balance in the selection of sources and arguments in the leading German newspapers’ coverage of the census issue’. European Journal of Communication 8 (3), pp. 317–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323193008003004 .

-

Hamburg, D. A. (1999). ‘Foundations and science policy’. Science 284 (5412), pp. 259–259. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.284.5412.259 .

-

Haverland, M. (2009). ‘How leader states influence E.U. policy making. Analysing the expert strategy’. European Integration Online Papers 13. URL: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1553787 (visited on 22nd January 2019).

-

Heisterkamp, U. (2014). Think Tanks der Parteien? Eine vergleichende Analyse der deutschen politischen Stiftungen. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06858-5 .

-

Jarren, O., Oehmer, F. and Wassmer, C. (2010). ‘Konfliktbearbeitung in der Politik. Eine Sprachanalyse von Parlamentsdebatten in der Schweiz und Deutschland’. In: Wahl der Wörter — Wahl der Waffen? Sprache und Politik in der Schweiz. Ed. by K. S. Roth and C. Dürscheid. Bremen, Germany: Hempen Verlag, pp. 33–62.

-

Knight, C. and Lyall, C. (2013). ‘Knowledge brokers: the role of intermediaries in producing research impact’. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 9 (3), pp. 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426413x671941 .

-

Kocka, J. (2004). ‘Die Rolle der Stiftungen in der Bürgergesellschaft der Zukunft’. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte , pp. 3–7.

-

Lange, H. (2010). ‘Innovationen im politischen Prozess als Bedingung substantieller Nachhaltigkeitsfortschritte’. In: Soziale Innovation. Ed. by J. Howaldt and H. Jacobsen. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92469-4_11 .

-

Leat, D. (2016). Philanthropic foundations, public good & public policy. London, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Niedermayer, O. (2015). ‘Das deutsche Parteiensystem nach der Bundestagswahl 2013’. In: Die Parteien nach der Bundestagswahl 2013. Ed. by O. Niedermayer. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien, pp. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-02852-7_1 .

-

Pautz, H. (2012). Think-tanks as interfaces between policy, politics and expertise. London, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Pautz, H. (2013). ‘The think tanks behind ‘Cameronism’’. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 15 (3), pp. 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2012.00518.x .

-

Peters, H. P. (2012). ‘Scientific sources and the mass media: forms and consequences of medialization’. In: The sciences’ media connection — public communication and its repercussions. Ed. by S. Rödder, M. Franzen and P. Weingart. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Netherlands, pp. 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2085-5_11 .

-

— (2013). ‘Gap between science and media revisited: Scientists as public communicators’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (Supplement 3), pp. 14102–14109. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212745110 . PMID: 23940312 .

-

Renvert, N. (2011). ‘Die europäisch-transatlantische Dimension der deutschen politischen Stiftungen’. Zeitschrift für Politikberatung 3 (3-4), pp. 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12392-011-0273-0 .

-

Rimkutė, D. and Haverland, M. (2015). ‘How does the European Commission use scientific expertise? Results from a survey of scientific members of the Commission’s expert committees’. Comparative European Politics 13 (4), pp. 430–449. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2013.32 .

-

Rodari, P., Bultitude, K. and Desborough, K. (2012). ‘Science communication between researchers and policy makers. Reflections from a European project’. JCOM 11 (03), C07. https://doi.org/10.22323/2.11030307 .

-

Rohe, W. (2016). ‘Wissenschaftsförderung als gesellschaftliche Aufgabe privater Stiftungen’. In: Handbuch Wissenschaftspolitik. Ed. by D. Simon, A. Knie, S. Hornbostel and K. Zimmermann. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Fachmedien, pp. 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-05455-7_16 .

-

Ruser, A. (2018). Climate politics and the impact of think tanks scientific expertise in Germany and the U.S. London, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Sarkki, S., Niemela, J., Tinch, R., van den Hove, S., Watt, A. and Young, J. (2013). ‘Balancing credibility, relevance and legitimacy: a critical assessment of trade-offs in science-policy interfaces’. Science and Public Policy 41 (2), pp. 194–206. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/sct046 .

-

Scherer, H. and Baumann, E. (2002). ‘Medien in der parlamentarischen Debatte. Eine empirische Analyse von Medienverweisen in den Debatten des Niedersächsischen Landtags’. In: Integration und Medien. Ed. by K. Imhof, O. Jarren and R. Blum. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-97101-2_14 .

-

Schrefler, L. (2010). ‘The usage of scientific knowledge by independent regulatory agencies’. Governance 23 (2), pp. 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2010.01481.x .

-

Scott, J. and Jabbar, H. (2014). ‘The hub and the spokes: foundations, intermediary organizations, incentivist reforms and the politics of research evidence’. Educational Policy 28 (2), pp. 233–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904813515327 .

-

Scott, J., Lubienski, C., DeBray, E. and Jabbar, H. (2014). ‘The intermediary function in evidence production, promotion and utilization: the case of educational incentives’. In: Using research evidence in education. Ed. by K. Finnigan and A. Daly. Springer International Publishing, pp. 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04690-7_6 .

-

Sebba, J. (2013). ‘An exploratory review of the role of research mediators in social science’. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice 9 (3), pp. 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426413x662743 .

-

Strachwitz, R. G. (2010). ‘Foundations, definition and history’. In: International Encyclopedia of Civil Society. Ed. by H. K. Anheier and S. Toepler. New York, NY, U.S.A.: Springer US, pp. 684–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-93996-4_7 .

-

— (2011). ‘Stiftung’. In: Glossar Kulturmanagement. Ed. by V. Lewinski-Reuter. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92073-3_43 .

-

Thunert, M. (2004). ‘Think tanks in Germany’. In: Think tank traditions. Policy research and the politics of ideas. Ed. by D. Stone and A. Denham. Manchester, U.K. and New York, NY, U.S.A.: Manchester University Press, pp. 71–88.

-

Tremblay, M., Vandewalle, M. and Wittmer, H. (2016). ‘Ethical challenges at the science-policy interface: an ethical risk assessment and proposition of an ethical infrastructure’. Biodiversity and Conservation 25 (7), pp. 1253–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1123-9 .

-

van den Hove, S. (2007). ‘A rationale for science-policy interfaces’. Futures 39 (7), pp. 807–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.12.004 .

-

Vowe, G. and Dohle, M. (2009a). ‘Mediokratie oder Expertokratie? Ergebnisse einer Inhaltsanalyse von Parlamentsdebatten im Längsschnitt’. In: Identität und Vielfalt der Kommunikationswissenschaft. Ed. by P. J. Schulz, U. Hartung and S. Keller. Konstanz, Germany: UVK, pp. 283–298.

-

— (2009b). ‘Weltsicht und Medienbild des Parlaments im Wandel. Eine Inhaltsanalyse von Bundestagsdebatten aus 50 Jahren’. In: Politik in der Mediendemokratie. Ed. by F. Marcinkowski and B. Pfetsch. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 224–250.

-

Vowe, G. (2006). ‘Mediatisierung der Politik? Ein theoretischer Aufsatz auf dem Prüfstand’. Publizistik 51 (4), pp. 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11616-006-0239-4 .

-

Weingart, P. (2012). ‘The lure of the mass media and its repercussions on science’. In: The Sciences’ Media Connection – Public Communication and its Repercussions. Ed. by S. Rödder, M. Franzen and P. Weingart. The Netherlands: Springer, pp. 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2085-5_2 .

-

Welzel, C. (2006). ‘Politikberatung durch Stiftungen’. In: Handbuch Politikberatung. Ed. by S. Falk. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90052-0_26 .

-

Wigand, K. (2009). Stiftungen in der Praxis. Recht, Steuern, Beratung. Wiesbaden, Germany: Gabler.

Authors

Franziska Oehmer, Dr. works as research and teaching associate at University of Fribourg, Switzerland. E-mail: franziska.oehmer@unifr.ch .

Otfried Jarren, Prof. Dr. works as full professor at University of Zurich, Switzerland. E-mail: o.jarren@ikmz.uzh.ch .

Endnotes

1 Cf. http://www.cof.org/content/foundation-basics#what_is_a_foundation , 27. June 2018.

2 Typology of Foundations in Europe In: http://wings.issuelab.org/resource/typology-of-foundations-in-europe.html , 27 June 2018.